Killing Fairfax

"Sam Morgan suddenly had two big predators on his hands."

"Sam Morgan suddenly had two big predators on his hands."

BOOK EXTRACT

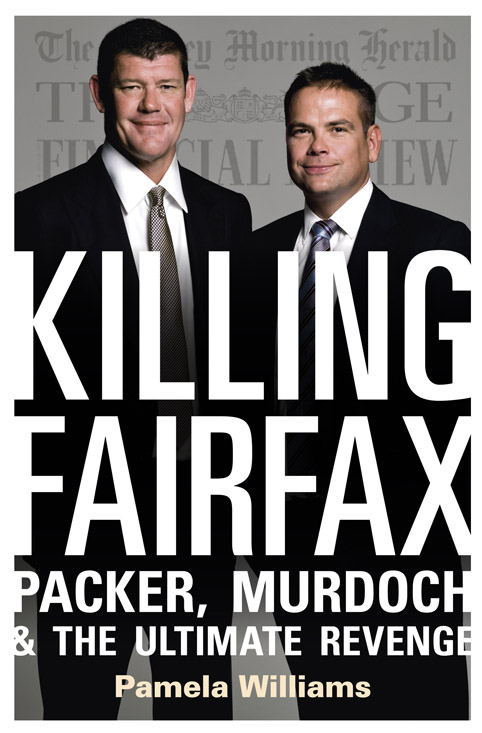

Killing Fairfax: Packer, Murdoch & the Ultimate Revenge, by Pamela Williams. Published by HarperCollins.

Our extract begins as Sam Morgan makes his decision between rival Trade Me suiters Fairfax and ACP. At the time of the action described in this chapter ('Rivers of red"), Ron Walker was chairman of Faifax; while James Packer's PBL owned publisher ACP (today owned by Bauer Media Group). The National Business Review - which has twice been part of Fairfax' stable - was owned by Barry Colman - CK.

A special Fairfax board meeting at 4 p.m. on 1 March 2006, held in the MCG boardroom virtually on the eve of the Commonwealth Games, endorsed the acquisition. The board later shared a three-course meal of smoked salmon, roast lamb and cheese as they discussed what other acquisitions might be on the horizon. The ACP New Zealand deal, which would have cost Fairfax $500 million, had been vaporised.

Sam Morgan said later that other more subjective factors than price had played into his final decision about which way to go. Like Morgan, David Kirk was a New Zealander and he made Morgan feel at home in separating from his baby. The Packer entourage left Morgan with the sense that he was an item on a menu.

I felt a lot more comfortable with Fairfax. With Packer’s people, I felt a bit like I was someone in an episode of The Sopranos, someone who might not still be there in the next series. There were five or six of them coming over in their private plane and they were all in suits and I was just in my usual T-shirt.

On 6 March 2006, Kirk announced that Fairfax had brought TradeMe for NZ $700 million (AUD $625 million). Packer had thought he would sell his magazines and acquire TradeMe, but he had lost on both counts: Kirk had dodged the magazines and won TradeMe. Ron Walker found that his hopes of peace in our time had evaporated, too, when an enraged James Packer confronted him nine days later at the opening of the Games as the Queen’s motorcade rolled into view.

But Walker would have the last word. On 20 March 2006 he wrote to Packer, chastising him for his behaviour at the Games and outlining the events that culminated in the collapse of the agreement to buy the ACP magazines. He did not mince words.

Dear James,

I was saddened to be exposed to your uncharacteristic rudeness and physical aggression on the evening of the Opening Ceremony of the Commonwealth Games on Wednesday last … let’s deal in the facts: In

late October or early November, John Alexander told me and David Kirk separately that TradeMe and the NBR [National Business Review] were two New Zealand assets that you were not interested in pursuing …

To our dismay, when finalising the purchase of TradeMe, we were informed that you had visited Sam Morgan in New Zealand, and had tried to convince him to treat with you and not us, citing your success with Seek. On 17 February, I briefly met with John Alexander and he told me he was prepared to sell your assets in NZ to Fairfax. On 19

February, whilst in London, I received a call from John saying that the deal was off, because of an article in the Sun-Herald that day …

On Saturday 25 February, you called me to say we should go ahead with the deal with John subject to due diligence and a meeting with the New Zealand Commerce Commission. On Monday 27

February, our CFO Sankar Narayan called Geoff Kleeman [PBL’schief financial officer] to arrange a meeting, and was told that he was away. I received a call from John Alexander in London a few days later to say that [radio and newspaper group] APN were interested and were seeking permission from their board to make a bid, and that I should hurry up, giving me the clear impression — for the second time — that you did not feel committed to a sale to us.

Days later, the TradeMe deal was completed and your personal calls to Sam Morgan were revealed, trying to convince him to complete a deal with you rather than with Fairfax. When I was told this I felt betrayed because of the consistent undertakings given to us by both you and John that you were not interested in pursuing TradeMe. It is a sad start to something that I had hoped would be a long-term relationship,

but I honestly hope that we can once again have another meeting and put things right.

I wish you well,

Ron

For David Kirk, a neophyte swimming in the deep and bitter pool of Australian media, the lessons of the ACP–Sun-Herald–TradeMe battle were capped off when he made a series of personal phone calls at Walker’s behest to apologise to Kerry Packer’s widow Ros and to Gretel and James Packer for the Sun-Herald item. Later, the Fairfax board grilled Kirk about how far the newspaper could go and where the boundary lay between good taste and bad taste, although no directions were given to the chief executive and the discussion ultimately petered out. Soon after, another apology was forthcoming, this time from James Packer, who wrote to Walker to apologise for his behaviour at the Games.

Packer recalled later: ‘There’s no doubt I was hoping that I could skin Ron and I probably did behave badly. Ron called me on it and I apologised to him, because I genuinely love Ron and we had been friends for a long time.’

Kirk regarded TradeMe as a significant achievement and it was consistent with his strategy to diversify revenue away from classified print advertising revenue in the metropolitan newspapers.

But he had not counted on the scepticism in the market and many analysts bagged him. The outspoken founder of 452 Capital, Peter Morgan, declared that there were bigger issues for Kirk to deal with than internet purchases in New Zealand. The announcement of the TradeMe deal overshadowed the half-year results to 31 December 2005, announced by Kirk on the same day.

A number of investors stood up in the meeting and asked him who he thought he was, going out and spending $600 million of the company’s money when he had barely been there for five minutes. Kirk held his ground, retorting that you didn’t have to be around for long to recognise a good business.

Kirk’s purchase of TradeMe in New Zealand was ridiculed too when compared to the AUD $552 million (US $580 million) paid in July 2005 by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp for MySpace, one of the hottest social networking sites in the world. (Later, MySpace would prove to have been a costly mistake: News sold it in 2011 for $35 million to a company backed by the singer Justin Timberlake.)

"Sam Morgan suddenly had two big predators on his hands. It was the first time anyone had acknowledged that Trade Me was making a lot of money, and outstripping Trade & Exchange and other competition. Sam Morgan in the Trade Me limo, 2006 (Courtesty Sam Morgan)

Kirk said he felt comfortable with TradeMe because he understood how it planned to make money for the next ten years.

He knew too, that he had out-manoeuvred James Packer and delivered to Fairfax the first online deal that really mattered — ten years after the early green shoots that gave rise to the likes of SEEK, realestate.com and car sales.

David Kirk’s appointment as chief executive of Fairfax bore more than a passing resemblance to a driver parachuting into the middle of a car race where the other competitors had been around the circuit several times and knew the treacherous bends and curves. But Hilmer had argued against recruiting a traditional newspaper executive, who would likely be beholden to the legacy print business, as his successor.

After 18 months of assessing and interviewing a number of candidates — including a failed attempt to recruit former News Corp executive Doug Flynn, who went on to run the pest-control firm Rentokil — Kirk was hired. As Hilmer departed and Kirk entered, the Fairfax share price was $3.80. Hilmer had added $1 in the seven years since he started in October 1998.

Kirk arrived at Fairfax’s headquarters in a modern and minimalist office tower at Darling Harbour in October 2005. The chief executive’s suite at the end of a curving wood-panelled corridor had been home to four previous chief executives — Stephen Mulholland, Bob Mansfield, Bob Muscat and Hilmer — over the ten years that Fairfax had rented the top nine floors of the building.

It was so far along the corridor that it had an isolated feel, as though chosen by someone who wanted no connection with the rowdy newspaper business that went on elsewhere in the building.

The notion that this was a clubby world apart was enhanced by the large, dark timber desk, the heavy newspaper stand and odd accoutrements like a remote control door-opener that lay on the desk and operated in such a way that the office door always closed with a bang, as though it had been slammed shut. Kirk soon ordered this to be disconnected.

Outside, Darling Harbour shimmered in the sunshine as sightseers and commuters hurried by.

There was nothing on the building’s soaring exterior to indicate that one of the greatest media empires in the nation dwelled within, aside from the throngs of journalists drinking coffee and gossiping in the forecourt at the Brolga Terrace Café. Kirk’s name was synonymous with rugby union, where he was known for his fiercely competitive nature but also for his legendary stance as one of two players who had refused to join the rebel New Zealand team touring apartheid South Africa in 1986.

In 1987 Kirk, as the 26-year-old captain of the All Blacks, had led his team to victory in the World Cup against France. He was famously photographed with his shock of rock-star hair and blood running from a cut over his eyebrow, triumphantly holding the golden Cup aloft. He quit rugby to take up a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford and later became a consultant at McKinsey.

As Kirk assessed his new empire in late 2005, he soon understood that Fairfax was facing potentially catastrophic structural challenges. Of greatest concern was the successful incursion of the pure-plays, the single-focus online advertising companies sending their root systems deep into Fairfax’s monopoly on jobs, cars and property classifieds. Fairfax seemed to have developed little of its own entrepreneurial spirit, perhaps by dint of its position as a venerable institution with a storied history. It was not involved in any of the independent online classified players aside from a small stake in the auto market leader, car sales.

Kirk found he had a number of executives deeply concerned about how to defend the classifieds. They included Alan Revell, who had been burned by Fairfax’s sluggish response to SEEK, but had overseen the acquisition from Yahoo of an 11.6 per cent stake in carsales, watered down months later to 7.6 per cent when the carsales founders joined forces with James Packer to defend themselves from Fairfax.

Fairfax’s ‘new media’ division was trying to make headway with the holiday homes website Stayz, and Kirk quickly decided to pounce on this property. He made his way onto the wavelength of the founder, Rob Hunt — a New Zealander himself, whose school had once played in competitions against Kirk’s school. The tiny $12 million deal was agreed by December, just weeks after the new chief executive had started at Fairfax.

Kirk resolved to run corporate strategy himself, but he hired an American with a background in telecommunications in New Zealand to report to him directly on internet strategy. Jack Matthews was an outspoken take-no-prisoners operator and he wasted little time on the niceties of buttering up journalists and embedding himself in the Fairfax culture. Matthews wanted to go the other way, to dig up the culture and truck in new soil.

Australia was in the midst of a jobs boom with advertising riding the wave, but Kirk was alarmed at how much revenue from the classifieds had been lost already. The prices charged for employment advertising

were under pressure and Fairfax was losing volume. MyCareer, the Fairfax jobs site, was limping along at best. Property advertising was holding on with more certainty, but Kirk could see that the competition from the Murdoch-controlled realestate.com.au was growing exponentially.

The vertical classified advertising streams in the metropolitan newspapers might be disappearing but it remained a Fairfax mantra that the company could be a significant number two in the online classifieds market — and, moreover, that the pure-plays were not an existential threat. There was only one business in the past that had ever dominated print classifieds and that was Fairfax: and so it would be in the future. Yet circulation, too, was under pressure and falling at The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. This played into the diminishing ad revenue as advertisers took note.

The biggest investment Fred Hilmer had made was the $1.1 billion purchase in 2003 of Independent Newspapers Ltd (INL), the New Zealand company then controlled by, and 45 per cent owned by, News Corp. INL had a dozen daily and weekly papers and dozens more free suburban papers fi lled with advertising. Hilmer was convinced that these publications would help to diversify Fairfax revenue as advertising was crimped by the attack of the internet on the Australian metro papers.

In March 2001 News had appointed Tom Mockridge to shake up INL and he had instigated a raft of cost savings and improved synergies. In early 2002, Hilmer and Mockridge had held a preliminary meeting to discuss a Fairfax bid for INL. Mockridge took it to the boss when he and Rupert Murdoch were in Milan in July 2002 for talks with Telecom Italia, which later led to the birth of Sky Italia. ‘Rupert thought about it for a millisecond and said, “yes”,’ Mockridge recalled later.

INL’s chairman was the veteran News Limited executive and director of News Corporation, Ken Cowley. Rupert and his son Lachlan, the head of the family’s newspaper operations in Australia and the US, were more bearish on New Zealand than Fairfax executives. The Murdochs were more bearish too than Cowley, who had confi dence in New Zealand and was reluctant to sell. But News was the Murdoch’s company, so Cowley ramped up the price. Fairfax initially offered $600 million, but that quickly mushroomed. Cowley pushed hard, forcing Fairfax to increase its offer three times. The numbers jumped sometimes by hundreds of millions of dollars.

Finally the Fairfax offer hit $1.1 billion, almost double the starting bid, and the Murdochs agreed. It was a spectacular deal for News. ‘The Murdochs were over the moon about it,’ Cowley recalled. ‘We got a lot more for it than they ever expected because they didn’t have any confidence in it business-wise or politically.’

Publicly, Cowley declared to the media that Fairfax had paid a significant premium on the book value: ‘Although INL’s directors were not actively seeking any expressions of interest in the publishing business at the time of the Fairfax offer, the offer was such that directors felt that the interests of the company and its shareholders would be best served by accepting it.’

The two-thirds of New Zealand’s Sky TV owned by INL was excised from the sale. After the sale to Fairfax and the wind-up of INL, News retained 44 per cent of Sky. Lachlan Murdoch said later: ‘Our long-term view of growth in New Zealand was negative. Fairfax came to us and we put a price on INL that was crazy, and we were almost shocked when they said yes. Tom’s work at INL had not yet paid off, but in the next two years it did very well.’

The withering headline on a research paper published by CCZ Equities’ Roger Colman on 23 May 2003, ‘NZ: is this Fairfax’s Vietnam?’ summed up much of the market reaction to the very full price paid, as well as concerns of a future downturn in growth in New Zealand.

Colman was a caustic critic of Fairfax but he produced the analysis to back his thesis; his view was that the competitor APN News & Media had the stronger newspapers, including The New Zealand Herald, which had the bulk of national advertising and thus premium earnings. He argued that Fairfax could hardly have paid a higher price and that real growth for New Zealand in 2004 was ‘forecast to lie between 1.5 per cent–2.5 per cent, down from 4.4 per cent in 2002’.

Hilmer would not countenance the criticism and he pointed out that the NZ assets would account for 30 per cent of Fairfax revenue. He predicted it would add 20 per cent earnings per share in the following year, diversifying the business and making it less reliant on the Australian advertising cycle and the metros. He was cutting costs inside the business and adding revenue from new sources.

But it was not this unprecedented billion-dollar investment by Fairfax that sucked up the oxygen amongst analysts and journalists in the weeks to come. Just eight weeks after the INL deal, the news that bit hard into Fairfax was the stunning revelation that James Packer had bought into SEEK for what seemed like small change by comparison.

Hilmer had paid $1.1 billion for INL and Packer had paid just $33 million for 25 per cent of SEEK. Hilmer described this fi gure as over-priced and not what Fairfax would have considered paying. But SEEK was hot property and Packer’s tilt realigned the gulf between old and new media. The deal received wall-to-wall coverage, with profi les of SEEK’s founders, beaming photos, ‘insider’ stories of how the deal was done, and general acclaim for Packer’s perspicacity and the fact that Fairfax had been outwitted.

SEEK would change the dynamics in the way media companies were viewed. On 5 August 2003, the day after Packer’s investment was announced, Macquarie Research’s leading media analyst Alex Pollak issued a devastating paper on Fairfax titled ‘SEEK: where the jobs are hiding’.

POSTSCRIPT: Today, Sam Morgan is a Fairfax director. Fairfax floated Trade Me in December November 2011 and sold its remaining 51% stake in December 2012 for $A600 million to pay down debt. James Packer's Consolidated Press Holdings sold its 26% stake in Seek for $A441 million in August 2009. It has recently rebuilt a small holding - CK

Extracted from Killing Fairfax: Packer, Murdoch & the Ultimate Revenge, by Pamela Williams. Published by HarperCollins.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.