How Britain’s ‘bad boy’ artist sped the dying days of Soviet Union

OPINION: A London art dealer's racy account of his audacious Francis Bacon exhibition in Moscow.

OPINION: A London art dealer's racy account of his audacious Francis Bacon exhibition in Moscow.

The world of contemporary art doesn’t rate highly in popular culture. Most books, both fiction and non-fiction, emphasise its fringe appeal, as well as its penchant for fraudsters, scams and dependence on the financial ‘greater fool’ theory. Non-fungible tokens stored on blockchain are just the latest example of this phenomenon.

In the movies, recent examples include The Burnt Orange Heresy, based on a 1990 thriller by Charles Willeford and starring Mick Jagger as a dodgy art dealer and Donald Sutherland as an artistic recluse. Another is The Artist’s Wife, in which the titular character passes off her work for that of her husband, who has dementia. Both depict the art scene as superficial and those who invest in it as suckers to be plucked like golden geese.

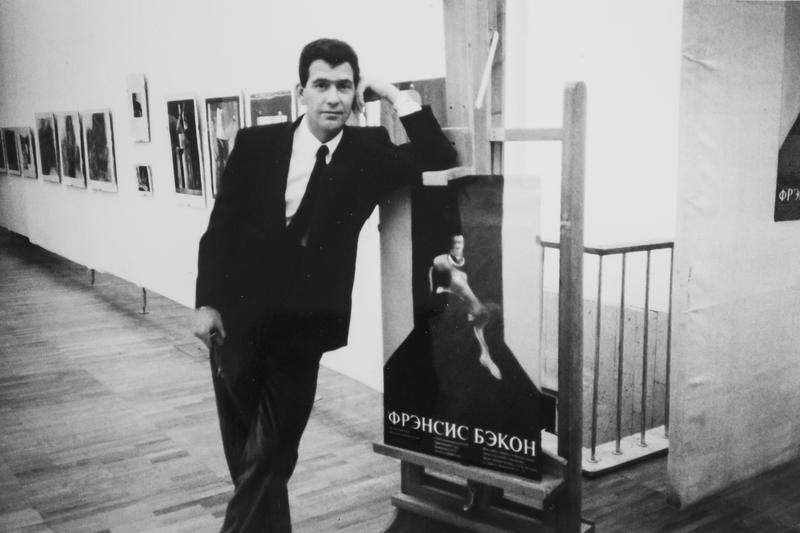

A more benign view, from the inside, comes from London dealer James Birch, who in Bacon in Moscow presents a racy account of how an exhibition by one of Britain’s best-known 'bad boy' painters, Francis Bacon, was staged in the dying days of the Soviet Union.

This may not be the best time to write or read about that time, when Russia is waging an outrageous war against its closest neighbour, but nostalgia has a powerful appeal to anyone interested in the Soviet Union and its culture. That means lots of shady characters, the dark corridors of power, and motives that are less than transparent.

As a child, Birch grew up in a family addicted to art. He recalls staying in East Anglia with his grandmother, who was a neighbour of Dicky Chopping, designer of the original James Bond book jackets. Bacon often stayed with Chopping and even photographed the young Birch in the bath.

In his 20s, Birch was promoting surrealist artists in London, notably the exhibitionist Neo Naturists. They performed naked, painted in primitive designs by transvestite ceramicist Grayson Perry. Birch’s gallery later moved to Dean St in Soho, where Karl Marx had once lived. That got Birch to wondering whether the Soviet Union was ready for western contemporary art.

Exploratory visit

An exploratory visit to Moscow in 1986 soon put paid to notions that the Soviet Union would allow any form of art that involved sexuality, let alone nakedness. The KGB had demonstrated its disapproval back in 1974 with the so-called Bulldozer show. A group of underground artists had staged an exhibition in a forest near Moscow.

The secret service brought in bulldozers and a water cannon to destroy the works, burning and burying most of them in a tip. But in Moscow, Birch found a thriving artistic community, albeit one that operated under severe conditions and was largely ignorant of 20th century modernism.

But the best of them knew of western painters, and one in particular: Bacon. Thus was born the idea of staging an exhibition in Moscow, the first of any living artist since the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917. Birch had made contact with two of the key figures in his book: the mysterious KGB ‘fixit man’ Sergei Klokov, who often visited the West, and his glamorous associate Elena Khudiakova, a fashion designer and artist.

A second visit, in 1988, coincided with Mikhail Gorbachev becoming head of state, three years after he was made general secretary of the Communist Party. It was a time of change and a more liberal cultural environment, at least in theory.

Birch stayed at the Belgrade Hotel, a couple of years before I did, so I can compare notes. “The city creaked under a system of bureaucracy and over-staffing that slowed everything down but guaranteed mass employment,” he writes.

Doors start opening

In other words, not much had changed except that opening the door to western influences could no longer be actively resisted. (I was on a press trip for the first western journalists to visit Vladivostok for a conference.) With Andy Warhol ruled out due to his aversion to travel, Bacon was presented as an artist who restored figurative painting after World War II in contrast to the dominant trend.

“He created something much more profound than the abstract painters, he caught something about the mood of the age,” Birch pitched to the bureaucrats at the Central Union of Artists House, where the exhibition was to be held.

The British Council and Bacon’s dealer, the Marlborough Fine Art, followed through with 30 of Bacon’s works from 1945-88. The years of negotiations were worth it, the show was a sensation, with 400,000 visitors in six weeks.

But Birch’s story doesn’t end there. Bacon himself, then aged 79, didn’t attend, as had been intended. He had hoped to make a side trip to St Petersburg to see its collection of 20th century masters at the Hermitage, and had packed his bags, including Russian-language tapes.

Rather than the official reason of debilitating asthma, Birch blames art critic David Sylvester, who jealously guarded his role as Bacon’s confidant but was not invited to write in the catalogue. Bacon was told he would be in danger of being kidnapped while travelling on a Russian train.

Missing masterpiece

Another snafu was the absence of a Bacon masterpiece, Triptych – August 1972, in memory of George Dyer. The western media at the launch event blamed Soviet objections that it was pornographic. But Birch reveals it was self-censorship by the British Council, which decided the large, three-piece wouldn’t be acceptable and did not submit it.

Much of the book’s interest lies in Birch’s personal revelations. He never gets to fathom Klokov, the ‘fixit man’ who shadows him throughout and in whom he must place his trust. That ended when Bacon personally donated him a painting after a promise it would end up in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow’s leading gallery.

Bacon closely guarded such acts of generosity, so Birch was shocked when Klokov quickly sold the painting through Sotheby’s and pocketed the $500,000 proceeds. Klokov did not acknowledge feminism and engineered Birch’s proposed marriage to the designer Khudiakova, who did move to London but could not break her ties with Moscow. A 2000-page KGB file is testament to her reporting of Birch’s activities from 1985.

Birch blames the failure on the transactional nature of personal relationships in Soviet society, where sex was a currency of survival for women such Khudiakova, just as Marlboro cigarettes and condoms could be traded for services such as taxis.

In an epilogue, Birch notes the early deaths of his Russian characters – none lived to the age 60. Bacon, who was born in Dublin, died in 1992 aged 83 while on holiday in Madrid. His partner, John Edwards, who attended the Moscow exhibition and whose portrait featured on the catalogue cover, died of lung cancer in Bangkok in 2003, aged 53.

Bacon in Moscow, by James Birch with Michael Hodges (Cheerio Publishing in association with Profile Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.