Golden acres: Creating wealth from mānuka scrubland

First-hand history of Mangaorapa Station in southern Hawke’s Bay.

Gold Under the Mānuka: Mangaorapa Station, by Bill Mouat.

First-hand history of Mangaorapa Station in southern Hawke’s Bay.

Gold Under the Mānuka: Mangaorapa Station, by Bill Mouat.

The latest deluge of pessimism has drowned out a rare voice of economic optimism.

University of Otago associate professor Dennis Wesselbaum pointed out the long lag in recovery from a period of stagflation, a term most of his profession have avoided to describe the economy since the Covid pandemic.

Perhaps it’s Wesselbaum’s international outlook that honed his analysis that stagflation was a combination of aggressive fiscal stimulus, monetary policy mistakes (not raising interest rates sooner, for example), supply chain disruptions, tight labour markets, and global energy price shocks.

While a government cannot control all these factors, the political response was to ignore underlying structural weaknesses, particularly low productivity and persistent current account deficits.

The exit from stagflation is neither quick nor painless; the Government’s lack of popularity is just one symptom. Wesselbaum outlines three reasons for optimism.

First, the Reserve Bank, with its single mandate of price stability, has halved the official cash rate to 2.5% compared with 5% in 2023/24.

Second, the Government has committed to a fiscal policy that has brought spending under control without creating a sharper recession.

Third, the Government is committed to structural, supply-side reform, such as tackling long-standing regulatory bottlenecks, removing barriers to trade, and fast-tracking infrastructure and housing development.

While many will say these are not producing the desired results fast enough, Wesselbaum says this takes time. “Macroeconomic rebalancing is not a popularity contest. It is a matter of timing, sequencing, managing expectations and maintaining credibility.”

This long-term view is reflected in the history of Mangaorapa Station in southern Hawke’s Bay. Gold Under the Mānuka, by Bill Mouat, is more than just how three generations turned scrubland into one of the country’s most productive and admired farms. It’s also about the human qualities of hard work, dedication to a vision, and the ability to achieve it.

Mangaorapa Station in 1990, showing the air strip and hangar with the Pōrangahau coastal hills in the background.

The story begins with Bill Mouat’s grandfather, William (Billy) Mouat, the son of immigrant parents – the father from the Shetland Islands and the mother from Scandinavia. These pioneers arrived in the 1870s when southern Hawke’s Bay was being settled.

Billy Mouat established a trucking business, W Mouat Carrier, at Takapau in the 1920s when motorised rural transport was introduced. It quickly grew into a sizeable fleet of sturdy and reliable American-made REOs. The first foray into farming came in 1938 with the purchase of a 485-acre (196ha) block at Kōukanui.

Billy Mouat’s 1929 REO Speedwagon was fully restored in 1984.

Mangaorapa Station at Pōrangahau was the next major move. Billy’s two sons, Don and Max, sold the transport business in 1946, using the proceeds to purchase the first of the property’s two blocks. It was a bold step, considering the land was mostly covered in dense, 2m-high mānuka and kānuka. It was also infested with rabbits, wild pigs, and deer.

The land was considered unsuitable for farming and excluded from the Government’s settlement schemes for returned World War II servicemen. The brothers were in their 20s and had a comprehensive 10-stage plan.

It was detailed enough for the Bank of New Zealand to raise a mortgage. The station was in a lowly populated area with no electricity or habitable buildings. But the land was flat to rolling, with adequate stream water.

The priority was to clear the scrub, using heavy-duty Caterpillar D4 and Allis-Chalmers HD5 crawler tractors fitted with bespoke single-furrow scrub ploughs. The Mouat tradition was to buy the biggest and latest in farm vehicles and machinery. It dated from one of Billy’s sayings: “The cheapest thing you can buy is horsepower.”

The second half of the station was added in 1953, bringing the total to 4792 acres (1088ha). The Korean war-fuelled wool boom had put wind in the sails of all sheep farmers. But breaking in the second block was a bigger challenge. Some 30,000 rabbits were caught in the two years of the first phase in turning the scrubland into pasture. That tally took just one year at the second block.

Rabbiting during the scrub clearance on Mangaorapa Station.

Don Mouat took full control of the station in 1958, after Max sold his interest to buy another farm. It was a year in which the Labour Government imposed a rail-protection law that restricted private transport operators to 30 miles (48km) of the nearest railway station, in this case, Waipukurau.

This effectively stopped Mangaorapa Station, which had its own fleet of Bedford trucks, from taking its wool directly to Napier Port, or livestock to Whakatu freezing works. In a rare move, a judge granted unrestricted licences based on the “tremendous amount of work that has been put in by the owner”.

The judge’s decision, which also noted that “this farm operator is doing probably the greatest work to aid public interest”, was upheld on appeal. It wasn’t the only time the scale of what had been achieved at Mangaorapa was on public display.

In 1960, the Patangata County Council prosecuted Don Mouat for building without a permit. He was the council’s deputy chair and none of the councillors would vote for the prosecution until he suggested he would dob himself in. He said he was so busy building that “I don’t know whether I have a permit or not”, according to a newspaper report.

That building activity involved nine houses, shearers’ quarters, woolshed, machinery workshop, truck garage, cookhouse, dairy shed, and a dedicated office. The station also built a 20km network of all-weather roads and bridges. These were of such a standard that they were used for off-road rally competitions after the station was a base for a special stage section of the 1972 Heatway International Rally.

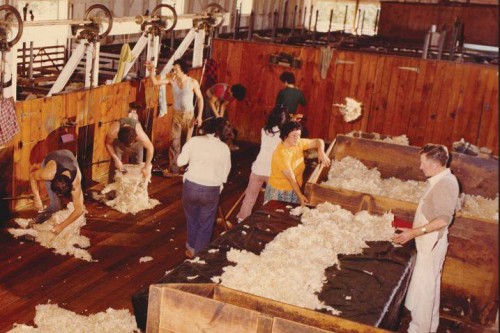

The woolshed at Mangaorapa Station.

Sheep numbers had exploded, increasing from 3000 in 1946 to a peak of more than 43,000 in 1968, as well as 1370 cattle. In 1970, a world shearing record was set when an eight-man gang sheared 3316 lambs in nine hours.

Mangaorapa was one of the few farms not to benefit from the 1977 Livestock Incentive Scheme to boost sheep numbers. It was already at maximum stocking rates. The scheme took the nation’s sheep numbers past the 70 million mark in 1982.

Meanwhile, Mangaorapa’s cropping area had reached 600 acres (243ha) by 1971, making this one of the country’s most intensively farmed operations. Staff numbers peaked at 23 in the 1970s, split between the stock department and the transport and agricultural division.

The station had a nine-hole community golf course until the late 1960s, when it was relocated to the new Pōrangahau Country Club near the beach. As club president, Don Mouat played a major role in the development of a clubhouse designed by Dutch-born architect Len Hoogerbrug, of Napier. He was also responsible for the station’s distinctive homestead, built in 1975.

The final phase of Mangaorapa under Mouat family control began in 1979 when Bill (the author) and his brother Bryan took over as equal partners from their father Don. They further expanded the operations with large-scale projects such as water storage dams, water reticulation systems, and reserve feed silage pits.

Dam building at Mangaorapa Station, 1973.

The station had its own airstrip and a Cessna 206 Stationair aircraft, piloted mainly by Bryan Mouat. But the early 1980s brought some rare setbacks. The stock subsidy scheme was abruptly removed in 1984 as the Labour Government implemented Rogernomics.

This came on top of a prolonged drought in 1982/83, the region’s biggest threat to farming. The 30% drop in national farmers’ incomes was exacerbated by the station’s large scale.

Livestock policies were changed dramatically, reducing numbers, as well as cutting back on fertiliser and capital spending for a couple of years. More emphasis was put on cereal crops. Land expansion was curbed after the last of three neighbouring blocks was acquired in 1990, taking the total station acreage to 6370 (2578ha).

Total livestock numbers peaked at 27,000 in 1991. It was followed by a radical reassessment that halved the ewe breeding numbers and replaced them with bull beef equivalents. The rebalancing target was reached in 1999 and doubled the turnover from the previous year.

Bill Mouat.

The speed and scale of change at Mangaorapa could not be replicated today, Mouat believes, given the tightening net of compliance and environmental requirements, as well as the increased cost of doing business.

In the 21st century, Mangaorapa diversified its operations into fertiliser spreading businesses, as well as winegrowing. But the decision to sell came quickly in 2005. The price was not disclosed but it was among the top farms sold that year.

The Mouat family’s latest generation was university-educated and showed no interest in carrying on such a large venture. The station is now run by two generations of the Anderson family.

While more than fulfilling the role of a family history, and recording it in minute detail, Gold Under the Mānuka will appeal to many whose lives have involved farming or servicing them. Mouat and his wife Carolyn – who did the investigative research, photography editing, and design – have produced an affordable ($50) coffee-table volume that stands apart from all but a handful of others.

It is lavishly illustrated with reproductions of letters, bank deposits, farm records, newspaper clippings, and pictures that complement the writer’s first-hand account. In consumer terms, like the early Pantene shampoo and more recent Mainland cheese advertisements, this is proof that good things take time.

Gold Under the Mānuka: Mangaorapa Station, by Bill Mouat (Bateman Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.