Huawei’s curse: Success brings security backlash

China’s telecom giant became too big for the West.

House of Huawei: The secret history of China’s most powerful company, by Eva Dou.

China’s telecom giant became too big for the West.

House of Huawei: The secret history of China’s most powerful company, by Eva Dou.

When the Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan absorbed southern China’s Song Empire in 1279, it was already the world’s workshop. It was the largest supplier of valuable ceramics, silks, jewellery, and other manufactured goods.

Nearly eight centuries later, nothing has changed. Southern China churns out a phenomenal amount of goods that everyone in the world demands. That includes most toys, appliances, and electronics, as well as cheap textiles.

It has steadily climbed to the pinnacle of industrialisation with robots and rockets, motor vehicles, high-tech machinery, commercial aircraft, and leadership in solar energy and battery power.

Throughout its existence, China has exploited its recipe of low-cost labour, innovative manufacturing, and ruthless efficiency. This is now complemented by the totalitarian power of the Chinese Communist Party.

The French newspaper Le Monde – which often goes where its English-language equivalents won’t – recently visited the headquarters of Shein in Guangzhou. Launched just a decade ago, Shein has become one of the largest global clothing giants without even targeting the Chinese market.

According to Le Monde, it inhabits neighbourhoods that operate in sync with the production of about one million garments, shipped in small parcels, that the fast fashion site can sell each day.

One of Shein’s many premises in Guangzhou, China.

Unlike Zara and H&M, Shein has resisted the temptation to outsource its manufacturing to even cheaper places such as Bangladesh or Cambodia. It considers that Chinese productivity alone can keep up with the sector’s formidable business pace.

"Here, the efficiency is double compared to Southeast Asia," a spokesman boasted. "China produces the raw materials, and we offer the models. Around Guangzhou, hundreds of thousands of people work in this sector."

Take the example of a 21-year-old worker. Her job is to fold clothes and put them into the brand's bags. Her days start at 8am, she gets a lunch break from noon to 1pm, another from 6pm to 7pm for dinner, then goes back to work for three hours in the evening, until 10 pm.

That makes for a 12-hour day. In some workshops, they work six days a week. Her earnings are between 6000 and 7000 yuan a month, equivalent to $1420 to $1660.

Shein’s success is emulated by dozens of other Chinese enterprises honed by efficient manufacturing. One of them is Huawei, the subject of House of Huawei, by Eva Dou. The book is subtitled ‘The secret history of China’s most powerful company’.

American-born Dou is a reporter for the Washington Post and has tracked Huawei’s transformation from a provider of telecommunications infrastructure into the corporate world’s major threat to United States security. This is because of the fear that its equipment – at its simplest, just ‘pipes’ through which data moves – could be ‘back doors’ for more nefarious purposes.

Eva Dou speaking at the Overseas Press Club of America in 2019.

Unlike the large-scale, state-owned Soviet model of industrialisation, China has always had a grass-roots network of workshops. Mao harnessed it in 1958 when he launched the Great Leap Forward with steelmaking in every village.

In the Soviet Union, Stalin financed industry at the expense of agriculture. Mao reversed that by putting the onus of industrialisation on the peasants. Foreign capital and expertise weren’t required. As Mao put it: “The humble are the cleverest, and the privileged are the dumbest.”

It produced some crazy outcomes, such as wooden cars and locomotives. It was also hugely wasteful, with houses being torn apart for building materials to achieve mechanisation. Mao’s obsession was steel (the meaning of ‘Stalin’ in Russian) and he measured the country’s success by how much could be produced.

A backyard furnace in Mao’s Great Leap Forward.

The campaign was a disaster in both human and economic terms. Much of the production was slag iron due to poor fuel for the kilns. Agricultural production suffered, leading to the Great Famine. It cost 45 million lives over the four years to 1962.

Four years later, newly graduated Ren Zhengei arrived in Guizhou Province in southwestern China. His job was to help build a fighter jet in a plant that could be hidden among the area’s picturesque hills and caves, but he would eventually end up as Huawei's CEO.

The Vietnam War was raging not far to the south, and Base 011 comprised dozens of factories spread over half a square kilometre to avoid detection. Ren, who had studied engineering, was first put to work as a cook. This was part of the re-education of ‘intellectuals’ during the Cultural Revolution.

Ren studied electronics in his spare time, and by 1974 was qualified enough to be posted to the Xi’an Instruments Factory in the northern Shaanxi Province, followed by a further move to a frontier site near the border with North Korea.

Here, while serving in the military, he became involved in China’s first attempts to manufacture nylon and polyester. The technology was provided by a French company, and Ren was soon absorbed in creating precision instruments.

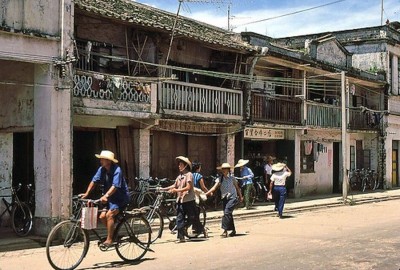

Shenzhen in 1980 when the Ren family arrived.

The death of Mao in 1976 ushered in a new era of modernisation. Ren and his wife, Meng Jun, a former Red Guard, moved to Shenzhen, where they worked for the Southern Oil Group. Ren’s 11 years in the military and membership of the CCP cemented the couple’s elite status.

Shenzhen was to become the catalyst for China’s export boom from the 1980s, with Huawei Technology being formed in 1987. From a modest contract manufacturer of telephone switches, Huawei became one of the world’s largest telecommunications companies.

An emphasis on research and development, and tapping top talent from partnerships with China’s top universities, enabled the charismatic Ren to seize the opportunities of globalisation when the internet and the digital economy took off. But that growth came at a cost.

“With Huawei increasingly integrated into global networks, it was being watched closely by spy agencies,” Duo notes. The National Security Agency (NSA) infiltrated Huawei and used its surveillance infrastructure to spy on the company, as well as other public and private entities, both in China and around the world.

Huawei’s US spokesperson, William Plummer, was able to observe: “The irony is that exactly what they are doing to us is what they have always charged that the Chinese are doing through us.”

Dou adds that it was no wonder Washington was so confident that Beijing could use Huawei’s gear for snooping: "The NSA had been doing that for years.”

Ren Zhengei outflanked his Western competitors.

It’s suggested these concerns were partly due to Huawei’s ability to outflank its Western rivals, such as Alcatel, Ericsson, Lucent, and Nortel. In 2005, the privatised British carrier BT awarded its 5G upgrade contract to Huawei, opening the doors to other lucrative deals.

By 2012, Huawei had become the largest company in its field and had expanded into smartphones and other branded electronic gadgets. It even started a music streaming business. But this success added to outside pressure.

A deal to buy US company 3Com fell through in 2008 (the companies had formed a joint venture in 2003). India was among several countries that followed US advice to veto some contracts. Japan’s Softbank was forced to sever its ties with Huawei so a takeover of Sprint Nextel could proceed.

Huawei chief financial controller Meng Wanzhou.

Huawei hit world headlines on December 1, 2018, when its chief financial controller, Ren’s daughter Meng Wanzhou, was arrested in Vancouver under an extradition order from the US. Nearly three years later, she was released from house arrest and returned to China. Two Canadians, both called Michael and unrelated to Huawei, were held as hostages until the matter was resolved.

Huawei continues to face bans and restrictions in multiple countries due to security concerns. Recently, Germany proposed a ban on Huawei and ZTE equipment, requiring telecom companies to remove their hardware from core networks by 2026. The European Union has also urged its member states to block Huawei from their 5G infrastructure.

In the US, lawmakers have pushed for sanctions on Huawei's cloud unit, citing potential security threats. Despite these setbacks, Duo wrote in 2024: “Yet – almost incredibly – Huawei was still number one in the world in 5G gear sales.”

Its corporate status remains opaque as a “collectively owned enterprise”, which acknowledges its role as a company crucial to China’s overall development. Dou admires its ability to “accomplish titanic tasks at almost impossible speeds” through methods exemplified by Shein.

The human cost is high, with stress-related illnesses a common complaint, along with suicides in extreme cases. Shenzhen, Duo concludes, offers a special environment for Chinese “capitalism” that meshes the ruthless business practices of innovation and efficiency with the CCP’s addiction to power in planning and control.

House of Huawei: The secret history of China’s most powerful company, by Eva Dou (Portfolio/Penguin Random House (US); Abacus/ Little, Brown (UK)).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.