Media matters: Rebuilding public trust

‘Boomer’ journalism blamed for decline in objectivity.

‘Boomer’ journalism blamed for decline in objectivity.

Reverberations continue in the media world from the BBC’s editing of the 2024 Panorama programme on President Donald Trump.

Michael Prescott, whose leaked memo resulted in the resignation of both the Director-General and the Head of News, this week appeared before the UK Parliament’s Culture, Media & Sport Committee. Under questioning, he said the BBC did not produce biased news.

“I didn’t use that phrase anywhere in the memo,” he was reported as saying. “Let’s be clear, tonnes of stuff [the BBC] does is world class. Everything I spotted [in the memo] had systemic causes and the root of my disagreement is the BBC was not treating these as having systemic causes.”

These were that the BBC refused to listen to criticism of its news coverage and was overly defensive. “There was never any willingness to look at what went wrong there, and there were deep implications,” Prescott continued.

In other answers, he said he didn’t agree with anything President Trump said and didn’t think the editing of his remarks would have done his reputation any damage. Trump has said he would sue the BBC for a billion dollars, though he has taken no legal action.

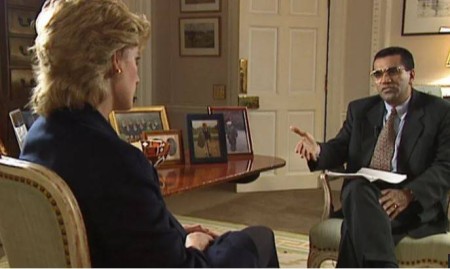

Meanwhile, Panorama is back in the news on another front: the 30-year-old interview with Princess Diana by Martin Bashir. A new book, Dianarama, by Andy Webb, a former BBC journalist, reveals more evidence of Bashir’s deceptions to gain the interview, as well as the cover-up that ensued.

A new book re-examines Martin Bashir’s interview with Princess Diana

Amid these stories, I was drawn to an account by yet another former BBC journalist, Graham Majin, on why a public broadcaster, funded by a licence fee rather than taxation, continues to face criticism that it largely ignores and fails to cater for the views of at least half the population.

These are the men and women who vote for right-of-centre parties in Britain who expect, like most of the population, for the news to be covered in an accurate, balanced, and impartial manner.

Majin’s analysis, published as Truthophobia: How the Boomers Broke Journalism (2023), traces the origins of truth-oriented journalism to The Times of London during the Victorian era and its adoption by major newspapers in the United States from the 1870s, starting with the Chicago Daily News in 1876 and most famously embraced by the New York Times.

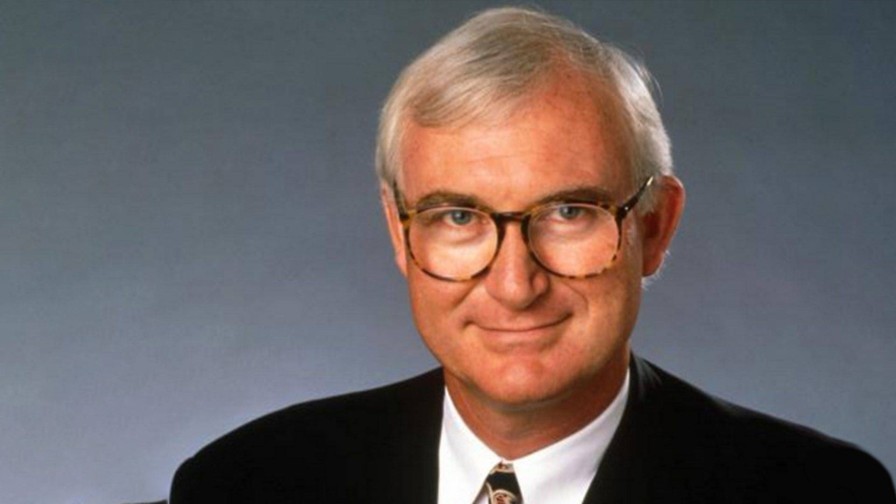

This credo was expounded in a 1954 essay by the then BBC Director-General William Haley and embedded by his successors until 1992, when John Birt decided this “dry and dull” search for the truth had run its course.

The “who, what, where, when, how” framework was to be preceded by “why?” In other words, factual reporting was to be replaced by explanation and commentary, which was previously restricted to editorial columns.

Lord John Birt was Director-General of the BBC from 1992-2000. (Source: BBC)

Birt (now Lord Birt) and his colleague Peter Jay, writing in The Times before Birt’s appointment to the BBC, declared Victorian journalism as no longer relevant. Instead, journalism should be about solving problems, and its role was to identify and explain a story’s wider narrative.

This approach had its critics, both at The Times and in the BBC, but it prevailed with a new generation of “boomer journalists”. In current affairs television, this meant senior journalists writing narrative scripts and junior reporters sent into the field to collect supporting interviews and footage.

In its most extreme form, which Panorama often displayed, celebrity journalists no longer pretended to be impartial bystanders but were participants in making the world a better place.

Majin argues this has resulted in two major defects in BBC journalism. The first is a reliance on narrative. In the simplest terms, this is good versus evil, with a core set of beliefs.

The second defect is sacrificing the truth for the narrative, resulting in one-sided storytelling. The Prescott memo cited the example of transgender stories. This had an echo in New Zealand the other week with the Government’s decision to ban puberty blockers, followed by a raft of stories that criticised it.

The tribulations of the BBC are relevant to New Zealand because it is a trusted source of news for many, including myself. Trust in journalism has also become an issue, with a recent report from the Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA) and Tim Watkin’s How to Rebuild Trust in Journalism.

The BSA report, Trust in News Media, runs to 66 pages and is compiled by The Curiosity Company from a national survey of 1008 adults, focus groups and a panel of 35 participants. Its findings reflect a decline in trust, from 53% in 2020 to 33% in 2024, below the international average of 40%.

It cites six reasons: misleading “clickbait’ headings; failure to correct errors; excessive opinion over factual reporting; aggressive interviews, ads disguised as news, and a range of other issues, including bias, misinformation and superficial reporting.

The solutions are those identified above as Victorian journalism: transparency and accountability; clear differences between fact and opinion; impartial reporting that avoids sensationalism; and avoidance of aggressive interviewing and emotional language.

Watkin goes well beyond the BSA’s data gathering exercise to provide a meaty roundup of issues that should concern anyone involved in media and communications. The author’s day job is executive editor of audio at RNZ, which makes him an insider. He has previously been deputy editor at the NZ Listener, producer of TV One’s Q&A programme, and founder of the Pundit.co.nz blog site.

His 212-page book is underpinned by an approach informed by moral philosophy. It was written on a study fellowship at the University of Glasgow’s philosophy department, and is the result of reading hundreds of reports, speeches, articles and books.

Tim Watkin

He identifies, like the BSA report, the four “superpowers” that make people trust journalism. The first is objectivity, fairness and accuracy; followed by transparency (“pulling back the curtain”); truth through verification; and care taken in presenting the news.

Early chapters outline the rise and fall of truth-based journalism. These draw heavily on historical research and a Reuters Institute study, Bias, Bullshit and Lies (2017), which outlines the same concerns as the BSA research.

This includes the belief that “media companies are distorting or exaggerating the news to make money”. It continues: “Over the last decade, digital advertising has become the most important income source … and this depends on generating the maximum number of clicks.”

Watkin interviews one of the authors, Richard Fletcher, and quotes him at length on the public distrust of commercialism and the motives of owners in the private sector. Of course, ‘clickbait’ is often in the eye of the beholder.

For example, I liked this recent heading on Stuff: “Trump’s radical idea that took everyone by surprise.” The only surprise, if you click, is that you aren’t.

In summarising these negative views, Watkin says: “Audiences are saying in all these surveys that they’re seeing too much clickbait, misery and spin, too many uncorrected mistakes, and not enough facts and context that enable them to make up their own minds.”

Worse, was “the distaste for sensationalistic journalism [that] was anchored in the feeling that such news was simply sought to provoke or trick audiences into clicking or watching,” according to the Reuters Institute.

Watkin goes on to examine the rise of journalism that supports the social criticism implied in the Birt-Jay thesis and “giving voice to the less powerful”. The danger here is that relentless coverage of social ills makes people believe the world is worse than it is. Birt and Jay are not quoted by Watkin, and nor is Factfulness, a study of public misconceptions first promoted by Hans Rosling.

Objectivity, a ‘superpower of journalism’, has become a whipping horse for the media, in Watkin's view. Rather than a century of objectivity having led to the lack of trust in journalism, Watkin argues it has been indifference to objectivity, along with the pull of social media, the loss of revenue and staff, and overall loss of trust in institutions that have done the damage.

He sees objectivity as a method, not a point of view, whose benefits are that it puts a priority on accuracy, separates priceless facts from opinion, protects independence, and establishes journalists as information experts. Two other qualities are that it upholds George Orwell’s dictum about the right to tell people what they don’t want to know, and reduces the risk of exaggeration in presenting a reliable view of the world.

When combined with verification of truth, transparency and humility in how the news is made and presented, the objective method is the best way to rebuild trust. While Watkin's means to reach this conclusion could be labelled “dry and dull” due to its lack of egregious examples of bad journalism, it provides a wider context to advance the BSA’s local research.

How to Rebuild Trust in Journalism, by Tim Watkin (BWB Texts).

Further reading:

Trust in News Media (Broadcasting Standards Authority/The Curiosity Company).

Nevil Gibson is a former Editor at Large of the NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.