Pretty poison: The rise and fall of Veronal

ANALYSIS: Devonport nurse’s deadly sleeping potion scandalised a nation.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Devonport nurse’s deadly sleeping potion scandalised a nation.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

If something causing death doubled its toll in five years, you would expect public outrage and calls for something to be done. Yet in the US, a single synthetic drug, up to 50 times more potent than heroin, is doing that with little being done to stop it.

Fentanyl has long been used as a powerful painkiller in hospitals. In New Zealand, it was linked to a case in Wairarapa where 12 people were hospitalised over a 48-hour period in 2022. Half were unconscious after heavy doses. The drug was illegally supplied and, to my knowledge, the case remains unsolved. The NZ Drug Foundation cites it as a warning to support its drug checking service.

The foundation’s latest report – its second year as a licensed drug checking provider – comprised 2602 checks, a 50% increase. It found two-thirds of all substances tested were what was expected. Of the remaining third, 22% of the total tested was not known beforehand or produced an inconclusive result.

This left 15% that was either something completely different than expected or was a mix of what was expected and some other drugs. Samples of what was expected comprised MDMA, cocaine, methamphetamine, ketamine, and LSD.

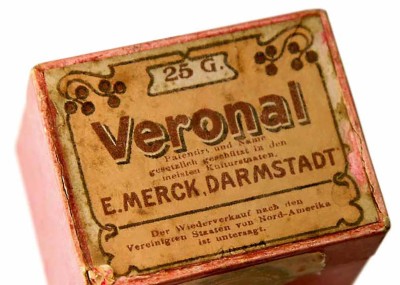

Veronal was widely available from its launch in 1902.

The foundation said it had also “identified several dangerous substances sold as other drugs recently, including powerful synthetic opioids called nitazenes, novel benzodiazepines, synthetic cathinones, and even non-psychoactive industrial chemicals such as cyclohexanamine”. Fentanyl was not specifically mentioned, though some of the substances named are said to be even more powerful.

In America, the Drug Enforcement Administration first raised an alert in 2014 about the illicit use of fentanyl. A decade later, the opioid was responsible for 70% of annual overdose deaths. Every 14 months, more Americans die from taking the drug than were killed in all the country’s wars combined since 1945.

The criminal activity in the illegal drug scene is about supply rather than administering it as a form of poisoning. Barbiturates, which Bayer first synthesised in 1902 to induce sleep, were introduced to the market as Veronal.

Every 14 months, more Americans die from taking [fentanyl] than were killed in all the country’s wars combined since 1945.

Variations followed and their recreational use outside of medical prescription soon became the drugs of choice in certain sectors of society. Famous writers and musicians became addicted to them, sometimes with fatal results.

In the 1920s, as deaths from overdoses of Veronal and other sleeping pills accelerated, availability remained high. In September 1929, an 18-year-old socialite in Sydney died after a “wild party” at which several well-known people admitted using Veronal for recreation.

In 1932, an Auckland coroner recommended Veronal be a prohibited poison after the death of an Avondale woman, who was an addict. His advice was not followed. But not long after, a series of sensational criminal trials involved Veronal as a suspected poison.

Scott Bainbridge.

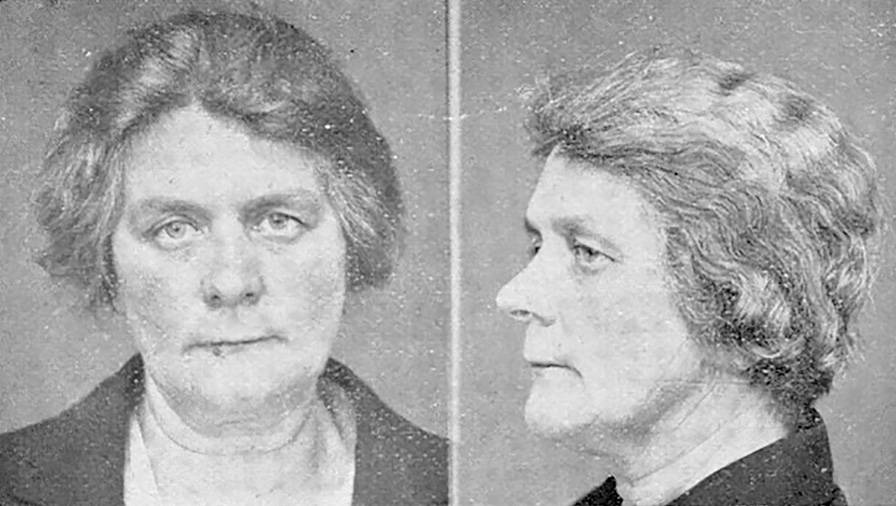

The trials resulted from the actions of a Devonport nurse called Elspeth Kerr, who was born Elizabeth McArthur in Scotland. She faced three juries on similar charges in 1933, unusual even today after two hung jury verdicts.

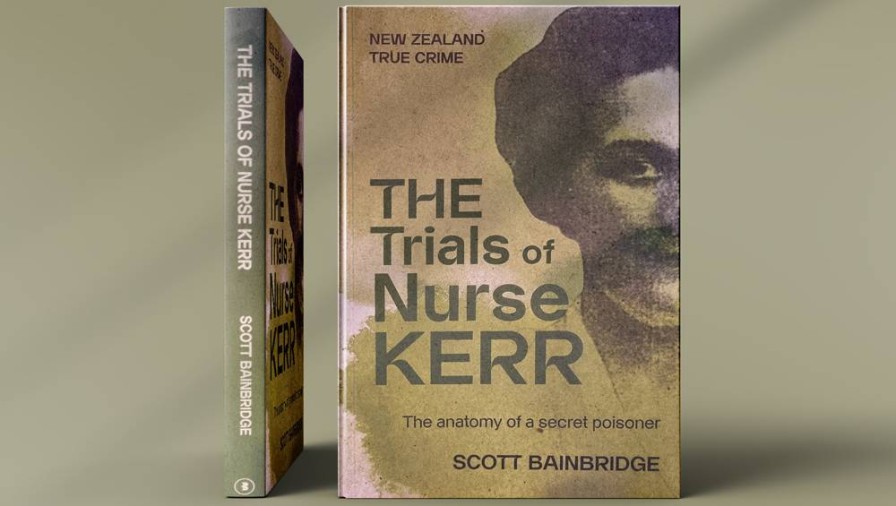

The Trials of Nurse Kerr, by true crime writer Scott Bainbridge, is a detailed account as well as providing context of today’s knowledge of drug abuse, addictive behaviour, and abuse of people in care.

Medical and legal ramifications followed, including the Poisons Act 1934. This made Veronal a prescription-only medicine. A decade later, it had been superseded by other sleeping pills or ‘downers’ that remained in use until the 1970s. Today, barbiturates are only prescribed for serious insomnia.

Richard Singer was Auckland’s leading defence lawyer in 1933.

Kerr’s lawyer, Richard Singer, highlighted the slack administration of drugs and samples at Auckland Hospital. He also exploited large holes in the prosecution case, including the lack of expert evidence on the effects of Veronal.

Fortuitously, Singer had the advantage of a brother in England who had access to the latest medical research that was unknown in New Zealand at the time.

Bainbridge’s description of Singer’s courtroom “antics” – which upset the judge with countless objections – said they were worthy of the best Hollywood could produce, while Truth newspaper kept the nation abreast of behind-the-scenes proceedings with several scoops.

These included an intrepid reporter-photographer witnessing two exhumations in the “grey mists of dawn” at O’Neill’s Point Cemetery, Bayswater, after an insider’s tipoff. The aim was to find evidence of Veronal in the sudden deaths of Kerr’s 49-year-old husband, Charles, in 1932 and one of her patients, who had suffered several strokes. Kerr was a close friend of that woman’s husband.

Truth led the coverage of the Kerr trials.

Until the first trial, Kerr was reputedly Devonport’s top midwife and owner of a private nursing home on Queen’s Parade overlooking today’s ferry terminal. She initially faced three charges of attempting to poison her foster daughter, Betty, then aged eight.

Betty was diagnosed with a kidney inflammation, pyelitis, and was being treated at home by Kerr. After falling ill several times and recovering each time, Betty was finally separated from her mother. Hospital tests showed Betty was positive for Veronal, which Kerr also used herself.

Throughout the three trials, the Crown did not argue that a motive was necessary; the mere act was the crime. The jury in the third trial delivered a guilty verdict in just over an hour, due to less assured evidence from Kerr’s personal doctor and the Crown’s greater confidence in its case, which was based on more knowledge about Veronal and its consequences.

Identikit pics of Elspeth Kerr. Photo NZ Police Archives NZ.

One was whether Veronal use could cause severe mental deterioration, including deliberate overdosing of a patient. Later tests, carried out overseas after the trials, showed that, unlike alcohol or opium, there was no tolerance in Veronal.

“Results varied but [addicts] … tended to be ‘a stranger to the truth, be dulled and hazy in action and speech, suffer from hallucinations and delusions, as well as developing craving for the drug. The moral sense becomes completely disturbed’,” Bainbridge explains.

The author also presents some background on offenders, often mothers, who cause or fabricate symptoms – such as suffocation, poisoning, or starvation – in those under their care. This is now known as ‘factitious disorder imposed on another’ (FDIA) – previously called Munchausen syndrome by proxy – or Medical Child Abuse.

Recent cases include Lauren Dickason, who killed her three children in Timaru, and Lucy Letby, a nurse who murdered seven infants and attempted to kill six others in 2015-16 in the UK. An FDIA expert, who gave evidence at Dickason’s trial, denied the accused was a victim of this syndrome.

Kerr served five of her six-year sentence. Her release on February 3, 1938, went unreported, as did her death in Parnell in 1969, aged 82. She had changed her name back to Elizabeth and lived with her son James toward the end of her life.

Interest in Kerr was quickly overtaken by a more sensational case a year later in 1934, that of flamboyant Auckland bandleader Eric Mareo, who was convicted for murdering his wife, the actress Thelma Trott, who was having an affair with the exotic dancer Freda Stark.

It was not until 1992, when building site excavations at 2 Matai Rd, Cheltenham, uncovered an adult skeleton, that interest in the Kerr case was rekindled. Though the Kerrs had lived there for a time after arriving in Devonport 1921, nothing could be linked to them.

However, another potential victim was identified. Vera Mason, a girl of similar age to Betty, was nursed by Elspeth Kerr and died in her care. Again, the symptoms were attributed to a kidney disease, uraemia, and no autopsy was performed. The possibility of Veronal poisoning was kept a Mason family secret until the Cheltenham discovery.

The author compiled a list of six others – four males and two females, apart from Vera – who died in Kerr’s private clinic. Two occurred between 1926 and 1930. All would have been treated with Veronal to induce sleep or relieve pain. Other causes of death, including cancer, were given, and one did not have an autopsy.

Bainbridge is a true crime professional, and the book reflects his expertise in missing people and cold cases. The first two of his previous eight books inspired the TVNZ series The Missing, while The Fix was shortlisted in the 2023 Ngaio Marsh Award for Best Non-Fiction crime writing.

Illustrations in his latest book show key personnel in the 1933 trials, locations around Devonport, and Truth’s front-page coverage of the first exhumation. Several appendices, source notes, and bibliography provide a valuable resource, though an index is missing.

The Trials of Nurse Kerr: The anatomy of a secret poisoner, by Scott Bainbridge (Bateman Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.