Taming the dragon: Can China keep going?

Call for the West to re-capture its get-it-done past.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, by Dan Wang

Call for the West to re-capture its get-it-done past.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, by Dan Wang

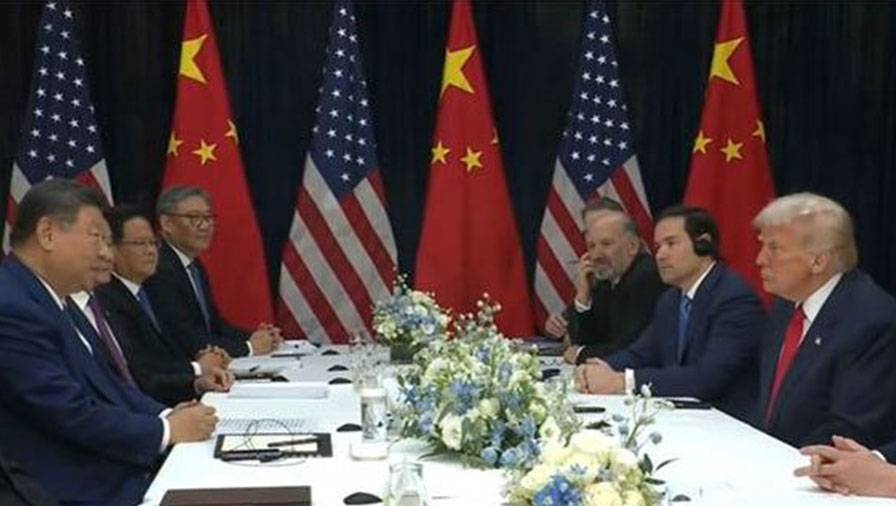

The latest summit meeting between President Donald Trump and his Chinese equivalent, Xi Jinping, met its low expectations.

From the limited available information, most of it from Trump, both parties have pulled back from the worst elements of a trade war while leaving most issues unresolved.

Countries trading with the United States have no counter for a president who issues or withdraws tariffs like party invitations. But China can deliver a robust response, such as banning the export of rare earths.

The Economist described the Busan summit outcome as a holstering of pistols, with China agreeing to lift its rare earths ban and the US suspending its 100% tariffs, as well as a threat of export controls on subsidiaries of blacklisted Chinese firms.

In addition, China will start buying American soybeans and take some action to limit exports of fentanyl ingredients. This is hardly earth-shattering, supporting the view that the agreement appears to be “sketchy and temporary”, meaning the world’s most important relationship continues to be “built on sand”, as The Economist put it.

The summit, despite being part of a wider Apec event, could have delivered more, considering it’s the first since 2019. It leaves an American tariff of 47% on Chinese goods, and Trump able to apply new ones any time he likes.

China’s President Xi Jinping meets US President Donald Trump across the table at Busan.

In turn, China can retaliate without consideration of world trading rules. The unstable nature of this relationship isn’t helped by the hostile commentaries emanating from both countries.

One book that tries to bridge the gap is Dan Wang’s Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

It starts with Wang’s contention that there are no two peoples more alike than Americans and Chinese. He lists materialistic, pragmatic, and get-it-done attitudes.

“A strain of materialism, often crass, runs through both countries, sometimes creating displays of extraordinary tastelessness, overall contributing to a spirit of vigorous competition,” he states.

He goes on: “Both countries are full of hustlers peddling shortcuts, especially to health and wealth”, and a “get-it-done attitude that occasionally produces hurried work”.

Dan Wang.

Wang draws political parallels as well, stating that while the elites in both countries distrust the broader public, all are united in the belief that, as the most powerful countries in the world, they have a right to push smaller ones around.

Wang writes with more experience than most other commentators. He has a foot in both camps. He was born in Yunnan, China, and emigrated to Canada with his parents when he was seven.

This was a backdoor to the US, as the family moved on to Philadelphia, where the parents still live, giving Wang a college education in New York and a job in Silicon Valley. He then moved to China, living in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai for six years from 2017 to 2023.

These were times when China’s economic dynamism gave way to increased political repression under Xi. Wang worked as a technology analyst for Gavekal Dragonomics, a company founded by Arthur Kroeber, a journalist who spent time at the NBR in the 1990s before moving to Beijing and editing the China Economic Quarterly.

As recently as August, Kroeber and Wang co-authored an article for the September-October issue of Foreign Affairs on the Chinese economic model, Made in China 2025. Today, Wang is a research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover History Lab.

The 2025 plan, released 10 years ago, identified 10 sectors for investment, including aerospace, energy, semiconductors, industrial automation, and high-tech materials.

“It aimed to upgrade China’s manufacturing in these sectors and others, reduce the country’s dependence on imports and foreign firms, and improve the competitiveness of Chinese companies in global markets,” Kroeber and Wang state in the introduction.

Welding robots in a Chinese distribution warehouse.

Breakneck is a record of how this plan has been put into operation, helped, it should be noted, by Trump’s attempts in his first term to tackle some of China’s egregious trade policies, such as theft of intellectual property.

These failed because, Wang argues, China is imitating policies that made America great, again underlying the two countries’ similarities. But America has gone in the opposite direction, becoming obsessed with procedure and what Wang calls an elite, mostly lawyers, who excel at obstruction.

This is a “lawyerly society” that blocks everything it can, good and bad. The US has 400 lawyers for every 100,000 people, which is three times higher than Europe. The profession is also becoming more feminised, with nearly 60% of law graduates being women.

By contrast, China is a technocratic state run by engineers, who can’t stop themselves from building things. By 2002, all nine members of the Politburo’s standing committee under Deng Xiaoping had trained as engineers. Not much has changed: Xi studied chemical engineering, and his all-male Politburo is filled with executives from the aerospace and weapons ministries.

China’s engineering achievements are remarkable. Its highway system is twice that of the US, the high-speed rail system is 20 times more extensive than Japan’s, and its solar and wind power capacity is greater than the rest of the world combined.

China’s high-speed train network is 20 times larger than Japan’s.

Its manufacturing base is equally impressive – a repetition of China’s imperial past when it was the world’s workshop long before the Industrial Revolution in the West.

Wang cites an example of how the US has turned its back on engineering. In 2008, both China and the US embarked on high-speed rail networks of about 800 miles (1290km) – Beijing-Shanghai and San Francisco-Los Angeles.

China opened its line in 2011 at a cost of US$36 billion ($64b). California has built only a small stretch of track in the Central Valley that won’t be operational until 2030 at a cost of US$128b. This triumph of process over outcome is symptomatic of a society that is biased to the well-off.

Wang won’t find many who will argue with this analysis and America’s woeful record in providing the basic social needs expected in modern welfare states. Despite Trump’s desire to bring manufacturing back to America, Wang says it will never recover from the loss of “process knowledge” that matches China’s “proficiency gained from practical experience”.

China has the capacity to produce 60 million cars a year out of an annual global market of 90 million. Its shipbuilding industry, which is making the new Cook Strait ferries, produced 1800 vessels in 2022 compared with only five in the US.

By 2030, China will have 45% of the world’s industrial capacity, while the US and all other high-income countries combined will have just 38%. Some 100 million Chinese work in manufacturing, compared with 13 million in the US.

However, Wang also recognises America will never follow China’s autocratic model, and that critics of Trump’s ‘kingship’ tendencies will never resemble the power Xi has over his people.

China’s shipbuilding far exceeds that of the United States.

In the past, that repression included a one-child policy that forced hundreds of millions abortions and sterilisations, and a zero-Covid lockdown that traumatised the middle class. That was also experienced by Wang, who says he missed the pluralism of America, where it is “wonderful to be in a society made up of many voices, not only an official register meant to speak over all the rest”.

Most of all, he missed being able to order books; ironically, some of them may have been made there.

Wang ends on an optimistic note that America, driven by curiosity, will look deeply into China and find reflections of its lost powers. For China, he sees a country that is breakneck in providing goods for its people, no matter how poor and remote, in return for keeping the Communist Party in power.

But these goods are dictated by engineers, who treat social issues as mathematical problems to be solved. The decision to reduce population growth has been reversed, but it has failed to revive births above replacement rates. The result is a demographic time bomb with a declining population.

Wang is a lively writer and injects a lot of personal conjecture into advising both countries on where they have gone wrong. The closing of China to the foreign media has made his observations more valuable at a time when curiosity about its economic model is essential if the West, and the US in particular, is to revive its successes of the past.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, by Dan Wang (Allen Lane/Penguin).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.