The day Russia blinked: Cuban Crisis revisited

British historian Max Hastings examines how a nuclear war was averted.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

British historian Max Hastings examines how a nuclear war was averted.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, 60 years ago this month, has a new relevance with Russian president Vladimir Putin threatening the use of “low yield” nuclear bombs against attack for his invasion of Ukraine.

The US has responded that this would lead to “catastrophic consequences” – a warning that has been sent to the Kremlin. But just how and where these bombs, and their fallout, would be deployed remains unknown.

The Cuban situation was much clearer, through records now available from the secret taping of White House decision-making as well as memoirs by many of the participants. British war historian Max Hastings has made full use of these archives in Abyss, his monumental 500-page account of events leading up to the deployment of nuclear weapons in Cuba, and their subsequent withdrawal.

He throws new light on why the records in the John F Kennedy Library show how desperate the Americans were when faced with the threat, and how they were groping in the dark to prevent the world from blowing up.

President John F Kennedy with flight crew who discovered the missiles in Cuba.

Kennedy and his advisers thought they were grappling with big strategic weapons – the sort North Korea’s ‘rocket man’ Kim Jong Un is planning to launch against the US. In fact, Soviet president Nikita Khrushchev had sent smaller, tactical nuclear war heads to Cuba – the sort that might be defined as ‘low yield’ or ‘dirty bombs’.

Hastings concludes the Soviet threats of nuclear attacks against the West were largely mythical, based on a bluff that Western strategists and – more importantly – their public believed the Cold War was being fought by two equals.

Undermining Western morale had long been a tool used to good effect by the Soviet Union, working through sympathetic organisations such as trade unions, ban-the-bomb movements, and ‘peace-loving’ anti-capitalists.

This was heightened by the launch of Sputnik 1 in October 1957, giving the Russians a propaganda victory. But the facts, as Hastings reveals them, is that Soviet technological achievements resembled Grigory Potemkin’s villages built in 1787 to impress Empress Catherine II during her journey to Crimea.

In the late 1950s, the Soviet Union lacked even the most basic consumer durables. In 1962, the year of the Cuban crisis, food shortages sparked riots throughout the USSR.

Khrushchev is depicted as believing “peaceful coexistence” was essential to the Soviet Union’s continued survival, but he never overcame his anger at the West’s superior wealth, military might, culture, and economic and social achievements.

This Russian sense of inferiority was not restricted to Khrushchev. It was a deep-seated feature throughout the Russian Empire’s history, as recently recounted in Orlando Figes’s History of Russia.

The nuclear threat from long-range rockets was Khrushchev’s key weapon in an otherwise scant arsenal. “Nuclear threats became his default weapons of choice,” Hastings writes. “... he privately acknowledged that he must not go to war with the West, because US nuclear superiority condemned the Soviet Union to annihilation. But he determined to exploit Western popular terror of such a conflict, to bluff his way to tactical successes abroad.”

This belief, and a strong streak of recklessness, contributed to Khrushchev’s decision to deploy nuclear warheads in Cuba. It was not a plan, Hastings contends, that would have been acceptable to Cuba if it had been thought through.

Khrushchev, like Russian leaders before and after him, feared encirclement by hostile forces. The US had achieved this through Nato and public defence treaties with the UK, West Germany, and Turkey.

Fidel Castro also wanted such a treaty to defend his revolutionary government against another invasion by the US. The Bay of Pigs, in 1961, had been a fiasco and brought instant ignominy to Kennedy’s new administration.

But rather than give Castro the conventional means to build a defence force, Khrushchev pushed for it to become a primary target in any nuclear conflict. His gamble did not end there. The deployment of weapons and personnel was enormous, and impossible to hide from even the most basic form of surveillance.

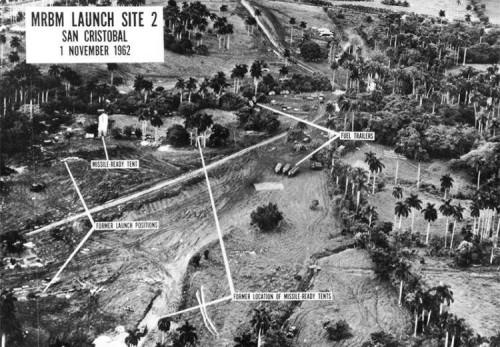

It required moving 36 medium-range (1200 miles) ballistic missiles, 24 rocket launchers, and 16 intermediate-range (2200 miles) missiles from their bases in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. The protection of these installations required 34 tanks, at least a dozen gun batteries, and more than 50,000 personnel. In addition, they needed supplies of food, fuel, accommodation, and other facilities to last an initial three months.

A Soviet missile launch site at San Cristobal, photographed on November 1, 1962.

Inevitably, the Americans noticed the extraordinary shipping and other activity, though an initial report on September 4 understated the deployment of missiles and MiG-21 bombers.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin was deflecting concerns and creating distractions such as threatening to seize Berlin to test American resolve at every turn. This included trying to get assurances the Americans were not going to invade Cuba.

The deceit continued as Khrushchev, in a bout of self-confidence, ordered even more missiles and the larger IL-28 bombers. His foreign minister Andrei Gromyko told top American officials a pack of lies but was fooled into thinking they had no knowledge of the missile buildup.

The weakness of the USSR’s nuclear arsenal, and the lack of any long-range ICBMs that are at the core of Khrushchev’s threats, had been known to the Americans through the KGB spy Oleg Penkovsky.

More high-altitude U-2 photos taken on October 14 confirmed the Americans’ worst fears as missile and gun sites had spread throughout Cuba. Planning for a military strike and invasion was stepped up, though it was the least of the White House’s options.

Direct military action through a blockade was the favoured course of action. Key news outlets were told to hold off any war plan stories until Monday, October 22. The tipoff was the first the New York Times had heard of the missile crisis.

The crisis continued until October 28, when Khrushchev capitulated against overwhelming American power. It took Castro another three weeks before he joined the agreement.

Former Daily Telegraph editor and historian Sir Max Hastings.

“The crisis that had come so terrifyingly close to war thus ended, without a bang but many whimpers: from disgruntled Soviet Presidium members, from Cubans, from US uniformed brass,” Hastings writes. The more than 50,000 Russians stationed in Cuba felt cheated, while Castro’s government was left without any of the IL-28 bombers.

When the dust settled, the US threats of bombing and an invasion won the day, as Khrushchev was unwilling to risk nuclear war. He had initiated the missile deployment, lied about it, and paid the price. Two years later he was ousted from power. The KGB spy Penkovsky, who alerted the West to the lack of inter-continental missiles, was executed in 1963.

Hastings gives Kennedy and his team the credit for resisting the more aggressive stance taken by the US military. He had done this by insisting that his actions be judged by their effects on the Russians.

The biggest losers were the Cuban people, who have had to live for the past 60 years under a repressive regime the US pledged not to overthrow but subjected to heavy sanctions.

In 1989, two years before the Soviet Union collapsed, Castro officially cut off ties, ending Cuba’s defence and economic dependence, much to the Russians’ relief. Cuba remains among the world’s least free and poorest countries.

Looking back from 2022, Hastings says the perverse outcome is that Russia continues to exercise a “baleful influence” on world affairs “from a strategic position of ever-worsening weakness”. He is not tempted to draw too many conclusions.

The world’s major powers are in a different environment from the Cold War. However, the threats to world peace are just as real, with trigger points such as Taiwan and Ukraine. Hastings reflects that today’s protagonists are a “mirror Image” of 60 years ago and the scope for a “catastrophic miscalculation” is just as great as Europe in 1914 and Cuba in 1962.

But China’s advances in economic and military power make it eight times stronger than Russia in 1962. Putin displays the same Russian insecurity that has dominated its history and, with the Ukraine invasion, has carried out an act of “far greater moral order” than Khrushchev did.

On balance, Hastings sides with the Nato quest to crush Putin’s aggression while pointing out that Putin, China’s Xi, and Kim in North Korea are “deficient for fear which must lie at the heart of wisdom” – and why Khrushchev rejected the nuclear trigger.

Abyss: The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962, by Max Hasting (William Collins).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.