Uzbekistan’s Silk Road is paved with gold

British journalist tests former Soviet socialist republic’s ‘experiment’ with freedom.

Silk Mirage: Through the Looking Glass in Uzbekistan, by Joanna Lillis.

British journalist tests former Soviet socialist republic’s ‘experiment’ with freedom.

Silk Mirage: Through the Looking Glass in Uzbekistan, by Joanna Lillis.

The price of gold soaring past US$5000 ($8300) an ounce for the first time is good news for some, but signals bad tidings for the rest. Wall Street analysts say gold could hit US$6000 by the end of the year.

A typical comment: “Gold crossing US$5000 reflects a deep reassessment of global power, policy, and capital. Investors are seeking certainty in an era where sovereign bonds and fiat currencies look increasingly fragile.”

That’s from Nigel Green, chief executive of deVere Group, who says the explosive rise in gold means a profound shift in how global investors perceive political risk, debt, and currency stability.

Later in the week, as gold rose to US$5500 and then corrected sharply, Green warned that "rallies driven by fear and momentum can reverse sharply".

In 2025, gold rose more than 60%, the largest increase since 1979’s 120% rise. In dollar terms, the US$1600 increase was the largest on record.

US President Donald Trump’s steamroller policies on trade, defence, and alliances are one reason. Another is the unsustainable debt levels in large and small economies. (Japan’s bond market is the latest red flag.)

“Gold is also reacting to a debt supercycle that shows few signs of reversal,” Green says. “When governments lean heavily on borrowing, investors hedge against currency debasement and long-term inflation.”

DeVere chief executive Nigel Green.

If there’s any good news, it’s for gold-producing countries. This came to mind while considering the shortening prospects of my overseas travel bucket list. I have already locked in South Africa, where record gold prices lifted the rand by 14% against the declining US dollar in 2025 and another 3% so far this year.

The rand now fetches 16 to the US dollar, its strongest since June 2022. However, I am unlikely to go down a gold mine, since my visit is to do with rugby and the All Blacks tour in August.

The Muruntau open-cast gold mine in Uzbekistan is the world’s largest.

Next on my list is probably some exposure to Central Asia and the historic Silk Road. Central Asia has two top-10 gold producers: Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which ranked 10th in the latest production figures from the World Gold Council. Uzbekistan's 129.1 tonnes compares with New Zealand’s paltry 6.6 tonnes, last on the list.

Uzbekistan’s 2025 gold exports hit US$9.9 billion in just the first nine months. The local price is up 16% in January. This has pushed national gold and foreign exchange reserves above US$60b, strengthening the local soum currency, narrowing the trade deficit, and supporting a projected 7.5% GDP growth.

This landlocked former Soviet republic is surrounded by four other ‘stans’, also once part of the USSR. Uzbekistan is the subject of Silk Mirage, by Joanna Lillis, a British journalist based in Almaty, the former capital and largest city in Kazakhstan. This country was the subject of her first book, Dark Shadows (2019), and is the result of nearly two decades in the region since moving from London to Tashkent in 2001.

Joanna Lillis.

Her reporting for The Economist was partly responsible for Uzbekistan being named as its Country of the Year in 2019. This was due to its radical transformation in the previous three years since the death of its strongman ruler, Islam Karimov.

It’s fashionable in some circles to disparage such changes as an ‘experiment’ – Helen Clark, Winston Peters, and Craig Renney have all done this to the neoliberal policies of the Douglas-Richardson era; or today’s critics of Argentina’s master reformer, Javier Milei.

But, as scientists know, human knowledge doesn’t advance without experiments. Neoliberalism means replacing state-controlled economies with ones that are market-based, usually with outstanding results.

Milei, an academic economist, described the process in The Economist (January 15, 2026): “Until the Industrial Revolution, population and income had been virtually constant for several millennia. Income per head moved from around $1100 (in current [US] dollars) in Roman times to just $1500 at the end of the 18th century. People lived roughly the same life generation after generation. Then came all those new machines and manufacturing processes. In the following 200 years, global wealth exploded. Population increased sixfold, and income per head tenfold. Poverty receded dramatically.”

Lillis gives full credit to Uzbekistan President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s ‘experiment’ in dismantling Karimov’s Stalinist socialist dictatorship while retaining enough power to ensure he can’t be derailed by dissident elements such as militant Islam.

Mirziyoyev was re-elected with an 87% vote for a seven-year term in 2023 after winning similar support for a new constitution that made him eligible beyond his previous two terms. The closest comparison for his leadership style would be Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew.

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev.

Modern Uzbekistan traces its history back to the Emirate of Bukhara and its short-lived republic founded by Fayzulla Khojayev as the Russian Empire collapsed during World War I. Under the Tsars, Tashkent had become a showcase ‘new city’ along Western lines, with wide boulevards, modern architecture, and innovation such as trams, telegraph, and rail by the end of the 19th century.

Its economy was based, as it still is, on cotton and silk production, though these were debased during the Soviet era with disastrous consequences for the environment as well as accusations of slave-like labour conditions.

The Bolsheviks crushed the fledgling ‘people’s republic’ based in Tashkent, but Khojayev remained in power until becoming a victim of Stalin’s purges in 1938. Stalin had carved up the whole of Central Asia into a patchwork of Soviet socialist republics, partly based on ethnic and language boundaries, while also imposing policies that purged ruling classes, banned Islamic education, and collectivised agriculture.

In 1929, the Uzbekistan SSR had its eastern part sliced off into Tajikistan while gaining control of the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan in the west and bordering the now depleted Aral ‘sea’. The Uzbek language was standardised over others, switching from an Arabic form to Latin at first, then to Russia’s Cyrillic alphabet in 1940, before reverting to Latin after the USSR imploded in 1991.

Statue of Fayzulla Khojayev in Bukhara.

In the post-Stalin era, Khojayev was rehabilitated by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and Karimov subsequently emerged as the Communist Party boss in 1989, well positioned to continue as a dictator with a wary attitude toward Moscow and obsessed with suppressing jihadists.

Tashkent hosted two million Russians, including its cultural elite, during World War II. It went through another physical transformation in 1966 after an earthquake left 300,000 homeless. The rest of the USSR pitched in, rebuilding parts in their own image and leaving one of the world’s best legacies of Soviet modernism.

The ‘Ukrainian quarter’ is widely admired among the city’s many attractions that include museums, the Chorsu Bazaar, a TV tower with a restaurant, and the fanciest metro in the world outside of Moscow. This makes Uzbekistan a good substitute for Russia, which is off limits for most Western travellers.

Both Karimov and Mirziyoyev excelled at attracting talented architects who, for better or worse, have dramatically changed the skyline of Tashkent, as well as the two other major historical cities of Samarkand and Bukhara. Lillis interviews one of these architects, Vil Muratov, along with a dozen or more leading artists, political dissidents, exiles, and others who have contributed to the ‘New Uzbekistan’.

The Kosmonavtlar Metro Station in Tashkent.

She visits Nukus in far-western Karakalpakstan, home to Igor Savitsky’s world-beating collection of Soviet avant-garde art that was suppressed until the 1990s. She also describes the role of two influential women, both daughters of the post-Soviet rulers.

Gulnara Karimova was notorious for building a billion-dollar fortune before her father finally engineered an end to her “lust for power, backstabbing, cupidity, [and] hubris”. She is still serving a prison sentence. By contrast, Saida Mirziyoyeva has presented a positive face to the world, promoting her country’s artistic achievements at important exhibitions in Paris (2022) and London (2024).

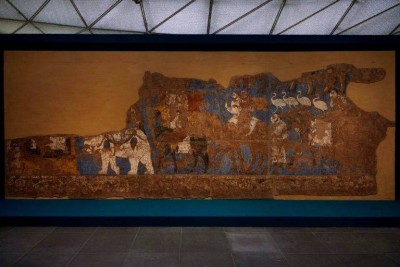

Uzbek art from the 8th century on display at the Louvre in 2022.

Lillis says her purpose is to show the “dazzling and charming” side that tourists see, while also going behind the façade to reveal the “monstrous and grotesque” features of a one-party state. As in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, that includes the continuation of a secret police service that propped up the Soviet era with its unchecked powers against any threats to the state.

Uzbeks no longer live in the fear of a closed society, with tens of thousands locked up for their political and religious beliefs. They have access to the internet and foreign media are welcome. The business and banking systems are no longer bound by export-import restrictions, draconian taxes, or strict controls. A once-thriving black market has disappeared.

The outside world has noticed. A report on Kun, a news website, says 11.7 million foreign nationals visited Uzbekistan in 2025, a 47% increase on 2024. While most (81.5%) were from neighbouring countries, improved air links brought more visitors from China, Turkey, India, and South Korea. Singapore and Malaysia are among countries seeking more traffic rights.

This book will whet your appetite to experience yet another ‘experiment’ that promises a better society.

Silk Mirage: Through the Looking Glass in Uzbekistan, by Joanna Lillis. (Bloomsbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.