Fleet Street and beyond: An editor’s memoir

Max Hastings left writing lucrative war books to revive a British national newspaper.

Editor, by Max Hastings.

Max Hastings left writing lucrative war books to revive a British national newspaper.

Editor, by Max Hastings.

Scandal is a core ingredient in the media and two have dominated the news in recent weeks on both sides of the globe.

In New Zealand, the McSkimming affair raised questions about the police that had parallels with the BBC bias row involving a documentary about US President Donald Trump. Both revealed internal cultures where denial, obfuscation, and cover-ups created doubts about the credibility of organisations that depend on public funding and accountability.

A discussion about the police is beyond the reach of this column but bias in the media is not. Public broadcasters, in New Zealand as well as Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, have long been the target for politicians and others for unbalanced programming.

It was not surprising that the latest involving the BBC came from a newspaper that has been described as the voice of the Conservative Party. This has some truth for The Daily Telegraph, although its conservative leanings did not emerge until the late 1870s.

It was founded in 1855 as a ‘paper of record’ – then a legal designation that meant it published official notices and court proceedings, or, in a wider definition, put an emphasis on accurate, detailed reporting of events.

On November 3 this year, the Telegraph published a leaked internal memo, running to 19 pages, by a former external adviser to the BBC's Editorial Guidelines and Standards Committee, Michael Prescott.

The BBC suggested the Capitol Hill riots were explicitly inspired by Donald Trump.

In it, he discusses in detail the Panorama special, Trump: A Second Chance? broadcast in October 2024. As is well known, it spliced footage of a Trump speech to give the false impression he explicitly incited the Capitol Hill riots of January 6, 2021, after losing the presidential election.

The memo also alleged senior BBC executives, including chair Samir Shah, had brushed off various serious complaints made to the editorial committee, and generally refused "to accept there had been a breach of standards".

This was, of course, no surprise to the Telegraph, and nor would it have been to other newspapers of the right to public broadcasting corporations in Australia and Canada.

Like the BBC, both the ABC and CBC are believed by critics on the right to follow a progressive activist agenda that excludes conservative views on a wide range of issues, from Gaza and climate change to race, religion, abortion, and particularly Donald Trump.

The BBC’s two most senior executives – its director-general and head of news – have resigned but did so without admitting there was any inherent bias as Prescott alleged.

Trump is now threatening to sue the BBC for a billion dollars, a tactic he has already used against some US media outlets with much expense to them and their credibility.

Meanwhile, in other breaking news, a £500 million ($1.16b) sale of the Telegraph to RedBird Capital Partners has collapsed. The parent company came under the control of Lloyds Bank after it called in loans from the Barclay brothers, who bought control in 2004 after the collapse of Conrad Black’s Hollinger Inc.

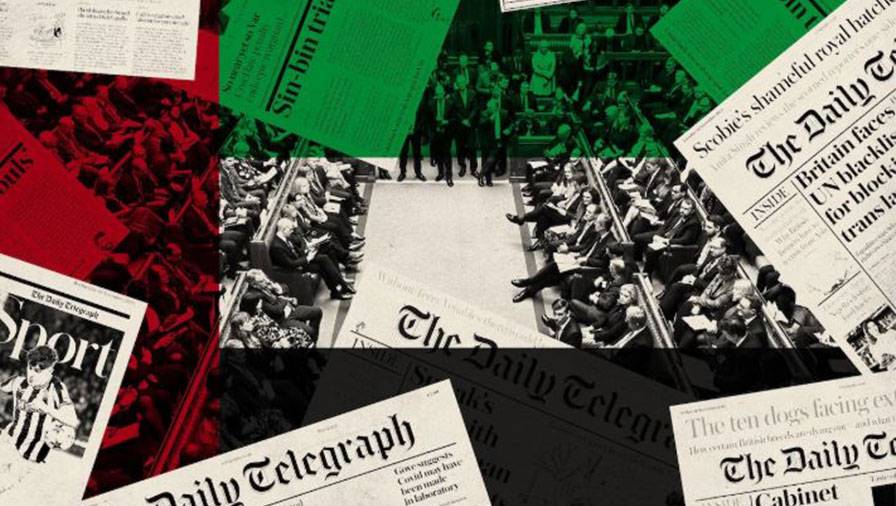

A Daily Telegraph montage showing House of Commons opposition to Abu Dhabi purchase.

Ownership of the Telegraph has been in limbo for three years after the UK Government passed a law prohibiting it from falling into the hands of foreign governments – in this case, RedBird’s backing from a fund run by the Abu Dhabi’s ruling family in the United Arab Emirates.

RedBird said its latest attempt to acquire the company was called off due to negative media coverage and regulatory scrutiny.

An earlier part of the Telegraph’s story is told in Editor, an account by war correspondent and historian Sir Max Hastings of his time running the Telegraph from 1986 to his exit in 1995. It has been issued in a paperback edition with an updated introduction but retains the full text of the original published in 2002.

Hastings was tapped for the job by Andrew Knight, a New Zealander who had been editor-in-chief at The Economist for 11 years and was Black's chief executive.

Sir Max Hastings.

Hastings was earning big money as a bestselling war book author and freelance correspondent. But he took a salary drop from annual earnings of £130,000 to head the Telegraph, known to Private Eye as the ‘Torygraph’.

Hastings was a contrarian hire, as he was a One-Nation Tory in the tradition of Benjamin Disraeli, the 19th-century prime minister who sought to bridge the divide between rich and poor through social reforms while preserving traditional institutions and maintaining a commitment to free enterprise.

By contrast, the 'Torygraph’ and its Sunday sibling were still fighting for the losing sides supporting Ulster Unionism, South African apartheid, and opposition to the European Union. Its owner, the Berry family, lacked the capital and the will to introduce new printing technologies against trade union resistance, or cull the ‘phantom’ workers and so-called ‘Spanish’ practices.

This led to a coup by Black and Knight, who took full control of a newspaper group that was still admired for extensive reporting of the courts and parliament, foreign affairs, sport, and business.

The British newspaper environment in the mid-1980s was volatile. Rupert Murdoch led the exodus from what was left of Fleet Street with the secretive move of his printing operations to a non-union site at Wapping. Ex-Telegraph journalists launched The Independent to a new generation of readers.

The Independent launched in 1986 and ceased printing to go digital in 2016.

Despite his lack of experience in editorial management, Hastings survived his nine years, cementing the Telegraph’s position as the leading broadsheet in a market where many considered it would be overtaken by Murdoch’s The Times and the new Independent.

He did this by making major changes in staffing and production, emphasising its strength in news with better-written stories, and improved layout. In the first two years of his editorship, three-quarters of department heads were replaced and a wider spectrum of opinions was introduced. The space for letters was cut back to eliminate regular but ill-informed writers.

The women’s page was eliminated and talented female journalists were appointed to senior positions. Another New Zealander, Nigel Wade, was appointed foreign editor. The paper’s biggest source of income was the Saturday edition, which was beefed up at a time when Sunday newspapers ruled the weekend roost.

An attempt to merge the daily and Sunday operations, to save costs, was abandoned because the Sunday Telegraph had a niche market for its quirky conservative views that provided a contrast to the dominant Sunday Times and The Observer.

British Prime Minister Sir John Major in 1996.

The Telegraph continued to lead the reporting of foreign events during 1986 to 1995. This included the collapse of apartheid, the end of the Cold War, the breakup of Yugoslavia, Irish terrorism, the fall of Margaret Thatcher, the Gulf War, and the Tory civil war over Europe.

Then, of course, there was the drama of the Royal Family, which no British newspaper could ignore. Editors of national newspapers were expected to be personally familiar with prominent members of royalty and the political establishment.

Hastings was no exception and the most interesting parts of his memoir are his endless lunches and dinners with key newsmakers, from Princess Diana to John Major, the hapless prime minister whom Hastings now concedes was much underrated.

Major was faced with a party riven by its pro- and anti-Europe factions. Hastings was relieved that his paper’s devotion to the Conservative Party could finally be downplayed, if not excised, by the rise of New Labour and Tony Blair.

Hastings was named Editor of the Year in 1988 and left the Telegraph in 1995 to edit the Evening Standard, London’s city paper. Two years later, Blair was elected prime minister in a Labour landslide. Hastings remained at the Evening Standard until 2002, when he was knighted on his retirement to resume his book writing – the war titles alone total 18 since 1979.

Today, he has few regrets about what he wrote in 2002 about his Telegraph experience. Apart from re-appraising Major, he defends his employment of Boris Johnson as a correspondent based in Brussels.

Boris Johnson was a ‘highly gifted entertainer’, according to Max Hastings.

In that role, Johnson often invented stories that appealed to his anti-Europe readers. Johnson was a “highly gifted entertainer”, according to Hastings, but “wildly unsuited to high office by reason of his extreme narcissism and indifference to other people”.

That withering opinion did not apply to Dame Margaret Thatcher, whose resignation in 1990 disappointed many at the Telegraph. But Hastings believes she met the “inevitable fate of national leaders who outstay their prudent span”.

Editor is an insider’s version of how a major media operation judges and presents news, opinion, and the impact of events on the community. While Hastings held values that were common several decades ago, recent events show why their loss is lamented by generations that shared them.

Editor, by Max Hastings (Pan Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large of NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.