Four women who breathed life into philosophy

Oxford scholars used metaphysics to challenge linguistic analysts.

Metaphysical Animals: How four women brought philosophy back to life, by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman.

Oxford scholars used metaphysics to challenge linguistic analysts.

Metaphysical Animals: How four women brought philosophy back to life, by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman.

The challenge that helped Wellington barrister Daniel Kalderimis KC out of his mid-40s depression through moral philosophy sparked one of my own. Not because I was depressed, but because I was interested in learning more about an intriguing episode in the history of philosophy.

A key element of Zest is how Kalderimis used philosophic concepts in dealing with other people by removing himself from the relationship. This originated in the ideas of Iris Murdoch and, before her, George Eliot. Both were novelists who wrote intensely about characters and how they related to each other. Plots were a secondary concern.

Both were also philosophers, though Eliot (real name Mary Ann Evans) did not publish any philosophical scholarship. She was, however, the first to translate Benedict de Spinoza’s Ethics (1677) into English.

Kalderimis was drawn to Murdoch through an essay on moral philosophy by Elizabeth Anscombe, one of a group of female scholars who studied at the University of Oxford and graduated in 1942.

Their impact on the tradition of British philosophy was dramatic and is now recognised as turning a subject once considered dry and analytical into one of metaphysical fascination.

Daniel Kalderimis KC.

This was confirmed in two group biographies published in 2022. In one of those rare coincidences that must drive publishers (and film studios) to despair, they cover the same ground.

The first, The Women are up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley and Iris Murdoch Revolutionised Ethics, is by Benjamin Lipscomb, a professor of philosophy at Houghton University in New York.

The other, Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life, is by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman, who are philosophy academics at the universities of Durham and Liverpool, respectively.

I have only read the latter, which is now available in a $25 paperback. A lengthy review of Lipscomb’s version indicates he covers a broader time span in fewer pages than Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman, who focus on the period from 1938 to 1958 and in much greater detail. The evidence points to both being thoroughly and independently researched.

Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman have the advantage of living in Newcastle, where they became friends with Midgley, who died aged 99. Her recall of personal anecdotes takes the story beyond one based solely on letters and documents.

Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman.

When these four women first arrived at Oxford as undergraduates, a strict ratio of four males to one female was enforced. But the outbreak of World War II upended this, as both eligible male students and academics were recruited into the services.

This left the university with only the older male professors, refugees, conscientious objectors, and female tutors to teach a predominantly larger proportion of female students. From all accounts, these bright young women made the most of it.

Some of the best parts of Metaphysical Animals describe the wartime exigencies of student life, such as the poor state of accommodation, the university buildings being used as hospitals, and the food rationing. But the pubs and socialising weren’t restricted and the female students spent much of their time fending off marriage proposals.

The quartet were all born in 1919 or 1920. Anscombe, who was the most formidable, was the first to marry, in 1941. Peter Geach was a fellow philosophy student and conscientious objector, who spent the war as a timber miller.

He was unable to secure a position after the war and was the primary caregiver for their seven children. They were apart for much of their early married life. Elizabeth was in Oxford and Peter in Cambridge, due to a lack of income to support a family.

Anscombe kept her surname and used her initials, GEM, in her published work, which was considerable. While the narrative weaves the stories of four lives, their philosophic work is threaded throughout.

Anscombe was admired on many fronts, though not for her untidy habits and preference for wearing trousers when Oxford’s dress code called for skirts. Her lectures became “legendary for the beauty of her voice, the foulness of her language and the depth of her thought,” the authors assert.

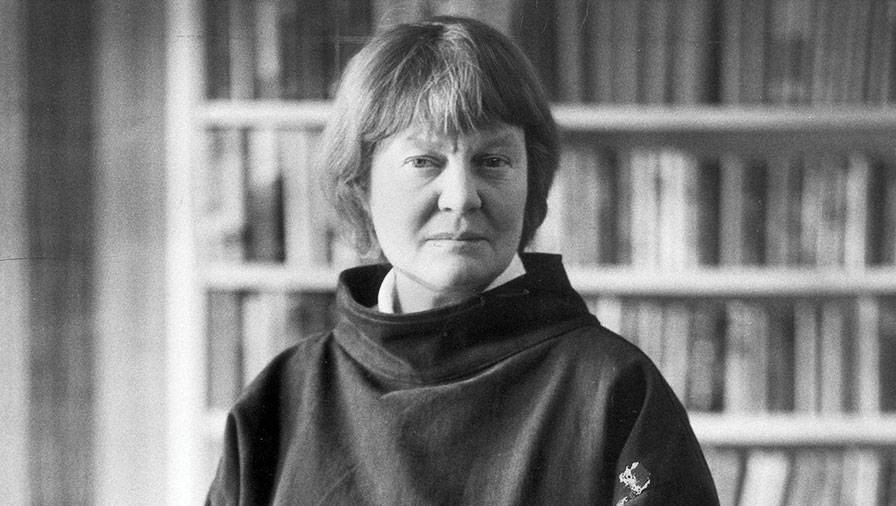

Elizabeth Anscombe revived Aristotle’s virtue ethics.

After the war, when the men returned to Oxford, Anscombe led the quartet in what Murdoch called “finding a way back to moral truth, objective value, and an ethics connected to what really matters” (this emphasis is in the original). This involved a full-scale attack on the dominant linguistic approach that restricted philosophic inquiry to logical, analytic, and scientific methods.

Anscombe demonstrated her skills in a 1948 session with CS Lewis, after which he foreswore further attempts at philosophy and stuck to writing fiction. Her substantial legacy was largely connected to the German logician Ludwig Wittgenstein, who arrived in Britain as a refugee from Nazism and whose works she edited and translated.

Philippa Foot in the 1970s. Source: Somerville College.

The wartime experience, with its unprecedented scale of atrocities that tested all opinions on morality, entrenched views in both men and women. Philippa Bosanquet, who spent the war years with Iris Murdoch in London, married Michael Foot, taking his name. (He was also Murdoch's former boyfriend.)

He had been a prisoner of war; and another like him, Richard (RM) Hare, had worked on the infamous railway over the River Kwai. Hare had the top professorial chair at Oxford, and his experiences in Burma led him to reject an objective set of moral standards that was at the centre of the women’s approach.

This difference was later described as a turning point in Oxford philosophy, with Philippa Foot and Anscombe credited as reviving Aristotelian virtue ethics at a time when philosophic debates had a high profile in the media as well as lecture theatres.

Foot put her ideas into practice, as a founder of Oxfam. Later in her long life (90 years), after moving to America, she switched from the metaphysics of morality to applied ethics. Her life’s work is summed up in Natural Goodness (2001), published just a few years before her death in 2010.

Iris Murdoch had by far the biggest public profile of the four, cemented by her reputation as a prolific and successful novelist, and appearances on television discussing the intersection of philosophy and literature.

Before returning to Oxford in 1948, she spent a year at Cambridge, just after Wittgenstein had moved on, and did war relief work in Europe, where she was exposed to the existentialist ideas of Jean-Paul Sartre.

Iris Murdoch was at the peak of her fame in the 1960s.

She translated his work and wrote a monograph on his ideas (1953), though she never fully embraced existentialism as suitable for ordinary civilian life. The centrality of ‘love’ in Murdoch’s published works was also reflected in her private life.

Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman draw heavily on her journals to depict her as a party animal, constantly taking and dismissing lovers, drinking, and debating until the early hours. One potential husband died of a heart attack.

Eventually she did marry, at the height of her fame, to literary critic and English tutor John Bayley in 1956, though the marriage produced no children. The authors coyly note, “she would continue to live many lives, with many people”.

Her final years, which are beyond the scope of Metaphysical Animals, were depicted in the film Iris, based on Bayley’s account.

By comparison, Mary Scrutton missed out on several academic posts after moving back to Oxford in 1948. She eventually became an assistant to Herbert Hodges at Reading.

He was also an opponent of logical positivism, while she kept up her profile with book reviewing on the radio, tackling writers such as Erich Fromm and Arthur Koestler. In 1950, she married Geoffrey Midgley, a philosophy professor, and they moved to Newcastle where they raised three sons.

Mary Midgley (nee Scrutton), bottom left, and Iris Murdoch, above right, at Somerville College, Oxford.

Unlike others in the Oxford quartet, Midgley championed gender issues and discrimination against women. These formed the basis of many radio scripts. But the BBC rejected one in the 1950s,‘Rings & Books’, because of a “trivial, irrelevant intrusion of domestic matters into intellectual life”.

It began: “Practically all the great European philosophers have been bachelors.” She then named 11 of them (Plato, Spinoza, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Kant, etc). Only three were married (Socrates, Aristotle, and Hegel). The authors add that they weren’t just bachelors but were “men who lived semi-monastic lives that excluded one half of the adult species and all of the species’ young”.

Midgley returned to academia in 1964, publishing her first book, Beast and Man, in 1978 when she was 59. Fifteen others followed, the last being What is Philosophy For?, a month before she died in 2018. If you are wondering about the answer to that last title, Metaphysical Animals is a good place to start.

Mary Midgley revived her career as a philosopher in her 60s.

Metaphysical Animals: How four women brought philosophy back to life, by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman (Vintage).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.