The atheist who wrote the greatest Easter novel

Why a Soviet masterpiece remains relevant in Putin’s Russia.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Why a Soviet masterpiece remains relevant in Putin’s Russia.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

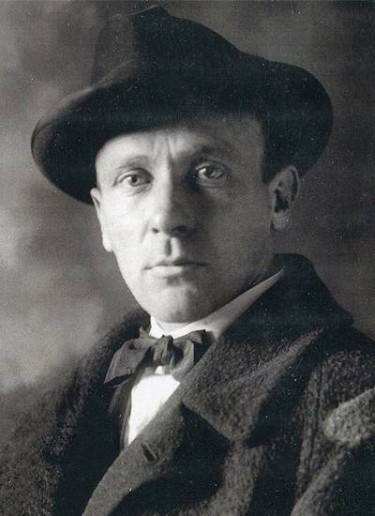

When Mikhail Bulgakov died of ill health (and suspected suicide) in 1940, aged 48, he had no idea whether his last novel would ever be published let alone become one of the 20th century’s greatest literary works.

Bulgakov was born in a generation that grew up when the Russian empire collapsed in a revolution, was embroiled in a civil war, and emerged as a totalitarian state that denied the certainty of science and religion.

He was on the losing side yet is back in the news in Putin’s Russia because of a new movie version of The Master and Margarita by a Russian-born American, Michael Lockshin, who made Silver Skates, the first Netflix movie in Russian. The movie was backed by Universal but its future release outside of sanctioned Russia is uncertain.

Meanwhile, audiences in Moscow and throughout Russia are flocking to see it, not least because they fear it may face the fate of Bulgakov’s books during the Stalinist period.

One of Bulgakov’s most lasting legacies from the novel is the phrase: “manuscripts don’t burn” – a reference to the writer’s role in a repressive society.

Mikhail Bulgakov (1928).

A Bulgakov scholar, Ellendea Proffer, provides this explanation: “All of Bulgakov’s literary energy and creative will were concentrated on proving something that his environment contradicted: that manuscripts don’t burn, that art outlasts tyrants, that entropy doesn’t triumph over the creative spirit.”

Just as many Russians joined the silent “vote at noon” protest in the sham presidential election last weekend, Bulgakov is idolised as the last of a classic literary tradition stretching back to Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Pushkin.

It makes no difference that Bulgakov’s birthplace, Kyiv, is now the capital of an independent Ukraine, no longer the Kiev of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, or the Russian Federation. Trained as a physician, he was a Red Cross medic for the losing Whites against Lenin and Trotsky’s Reds in the Civil War.

He witnessed a “great deal of torture and death”, rejecting his status as a monarchist White medical practitioner to embrace the lively cultural scene in Moscow as the Bolsheviks consolidated Soviet power. Plays and novels written during the 1920s reflected his wartime experiences as well as his knowledge of medicine, science, and religious beliefs.

But his career effectively ended with a blanket government ban in 1929, though a direct appeal to Stalin allowed him to continue working in theatre. Stalin’s protection saved him from arrests and execution but not from publishers’ rejection slips. Effectively exiled from public life, and in ill health, Bulgakov devoted the next decade to writing The Master and Margarita.

Fabio Merizzi’s painting depicting the Master and Margarita in the act of burning the manuscript (2020).

In 1939, he held a private reading for friends but it was not until 1966 that his third wife and widow, Elena, allowed the “unburned” manuscript to be serialised in a censored version in Moscow magazine. It was immediately recognised as a masterpiece, in Proffer’s words, because it was “dense with mystery, ambiguity and irony – a subversive work which fits no genre neatly”.

The novel opens with three characters in a theological debate on the existence of the Christian God and the Devil, the nature of good and evil, and the Easter story of Jesus Christ’s death on the Cross. One of them identifies as Woland, clearly the Devil, who ridicules the other two – a poet known as Homeless and Berlioz, the head of the Writers’ Union – for their defence of Soviet atheism as lacking in morality. This is a general condemnation of communism and a corrupt society.

The second chapter is a dialogue between Pontius Pilate and Yeshua (Jesus) that echoes the Gospels in the lofty language for which Bulgakov is famous. It strips away the messianic and mythical aspects of Christianity in favour of a humanistic alternative to organised religion. Pilate ridicules Yeshua’s belief in the inherent goodness of man.

The account is from a novel being written by the Master, the unnamed hero, who views the Easter story as one about the forces of politics and morality rather than Christ’s divinity. He is despondent because no-one will publish his work.

The rest of the novel is an alternating story of the Passion and the exploits of Woland and his retinue of magicians, including a large talking black cat, who create havoc at the expense of gullible and greedy Muscovites over an Easter weekend in the 1930s.

This includes a variety concert in which the audience is encouraged to help themselves in a Paris fashion house and grab money from the sky, only to find they end up naked and with empty wallets. Trouble also occurs at a foreign currency store and the Writers’ Union house, both of which have luxuries unobtainable to the ordinary Soviet citizen.

Much more is to come when Margarita enters the scene, agreeing to host Woland’s Satan’s Ball on Good Friday as part of her Faustian choice for a better future with her beloved Master.

The Mikhail Bulgakov Monument in Kyiv.

Legions of critics have analysed the many layers and literary allusions over the novel’s 400 pages (depending on your edition). You Tube has many examples, as well as a 10-part Russian TV series, dubbed into English (this is not Western-style dubbing but lines spoken by actors to accompany what’s on the screen).

Lockshin’s version has a two and a half-hour running time, according to its IMDB. Unlike the 2005 TV series, which closely follows the text, the Biblical content has been shaved back to focus on the Master and his conflict with the censors. This sounds as though it is more relevant to the Putin era than Stalin’s.

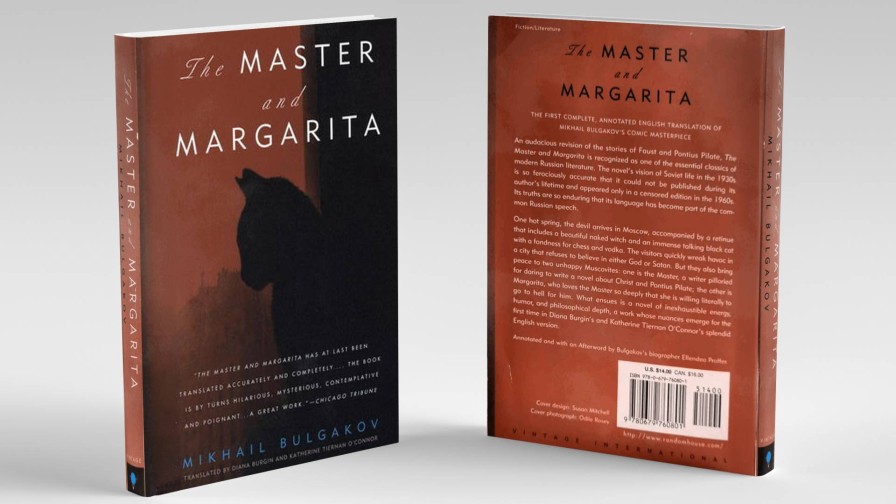

The Master and Margarita, by Mikhail Bulgakov, is available in several translations, the most common being those of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Penguin); Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O’Connor (Macmillan/Vintage); Hugh Aplin (Alma Classics); and Michael Glenny (Everyman).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.