Scent of history: Another side of George Orwell

ANALYSIS: The English literary giant viewed gardening as the essence of the good life.

Orwell’s Roses, by Rebecca Solnit.

ANALYSIS: The English literary giant viewed gardening as the essence of the good life.

Orwell’s Roses, by Rebecca Solnit.

The outrage against the bombing of Iran’s nuclear facilities is a reminder that some of the worst enemies of Western civilisation are those who live in it.

George Orwell put it best in a 1945 essay, ‘Notes on Nationalism’, where he critiques various forms of ideological bias, including pacifism. He was then at the height of his journalistic powers, having just published Animal Farm, a satire on the corruption of the Russian revolution into Stalinism.

Most were simple religious or humanitarian folk, Orwell observed: “But there is a minority of intellectual pacifists, whose real though unacknowledged motive appears to be hatred of Western democracy and admiration for totalitarianism.”

After World War II, several intellectual trends emerged that denounced or undermined Western civilisation. In France, postmodernists such as Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida attacked the ‘logocentrism’ of Western rationality and attempted to deconstruct the narrative of scientific and moral progress.

The neo-Marxist Frankfurt School of Critical Theory took root in the United States among émigrés from Nazi Germany. They attacked the European Enlightenment because it had paved the way for Fascism and the Holocaust.

Rebecca Solnit.

Another school were the social constructivists, inspired by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, who exposed modern science as just one of many mythological narratives. Science, they argued, did not so much reveal reality as construct its own reality – and an oppressive one at that.

Others included the interpreters of postcolonialism and environmentalists, who blamed Western civilisation for the evils of colonialism, cultural imperialism, and the degradation of the natural planet by industrialisation.

Amid this fervent of ideas, Orwell has stood the test of time. I have covered previous examples of Orwell’s continuing relevance. In one, I referred to his prescient depiction of the “authoritarian super-states of Russia and China in a world mired in the kind of endless warfare waged by the Islamist state of Iran”.

Another was Orwell’s Nose (2016), described by its literature professor author John Sutherland as a “pathological biography”. It analysed the role of smells in Orwell’s writing and his private life, much of it highly unflattering.

If Sutherland took a high-minded view of Orwell’s attitude to English class and habits, then American writer Rebecca Solnit goes all out on his embrace of gardening and the natural world. Solnit is a Californian who contributes to The Guardian and reflects its world view.

She has written 17 books, but I hadn’t heard of any of them if Orwell’s Roses hadn’t been plucked out of the shelves of Timaru’s independent bookshop for me by its canny bookseller after a brief conversation.

Solnit’s activism ranges across the spectrum from the environment and climate change to human rights and feminism. In 2014, she popularised the term ‘mansplaining’ in Men Explain Things to Me.

Politically, she is close to Orwell’s form of socialism, while acknowledging they belong to two different worlds. She admires how Orwell resisted complaints from his left-wing readers, who objected to his bourgeois references to nature and its simple but free pleasures.

George Orwell feeds a goat at Wallington, 1939. (The Orwell Archive)

Orwell was no Luddite and applauded the capitalists’ labour-saving devices of mechanisation that freed people of hard labour. But he was sceptical of utopianism and disliked aspects of industrialisation and urbanisation.

His early books – notably Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) and The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) – were vivid, first-person accounts of working-class life.

Solnit notes: “He distrusted absolutes and abstractions and theories that attempted to browbeat the actualities.”

She further records Orwell’s ability to divorce his lifelong addiction to horticulture from his political and cultural journalism. He prodigiously diarised all his planting and harvesting activities but never used them as a “springboard for flights of imagination or overt literary groundwork,” she writes.

It was an impersonal diary, without any emotional, social, or creative content. Solnit again: “In an age of lies and illusions, the garden is one way to ground yourself in the realm of the processes of growth and the passage of time, the rules of physics, meteorology, hydrology, and biology, and the realm of the senses.”

This is an introduction to the notion of “bread and roses” – originally a suffragette refrain and later adopted by the women’s labour movement. Bread symbolised home, shelter, and security. Roses represented life, music, education, nature, and books.

Roses, Mexico by Tina Modotti (1924). Platinum print.

“Bread can be managed by authoritarian regimes, but roses are something individuals must be free to find themselves …” Solnit writes. She segues into the life of Italian-born photographer Tina Modotti, whose 1924 closeup picture of Mexican roses became a genuine icon. Modotti’s political activity took her from California to Mexico, then a thriving hub for the world’s revolutionaries.

She was deported to Moscow in 1931 and, during the Spanish Civil War, betrayed some of Orwell’s associates among the anti-Stalinist elements in the Republicans fighting Franco’s Nationalists. Orwell and his wife Eileen, who adopted Orwell’s original surname of Blair, spent nearly a year in Spain before returning to their country cottage in Wallington, Hertfordshire, where they ran a small shop and farm.

Modotti later fell victim to Stalin’s assassination network with her death blamed on her partner who was involved in the plot against Trotsky.

Another deep dive into one of history’s interesting characters concerns geneticist Charles Hurst, who studied the genealogy of the rose. Orwell tapped Hurst for knowledge about Stalin’s promotion of the fake science of Trofim Lysenko and their victim, Nikolai Vavilov, founder of the famed Leningrad seed bank that survived the World War II siege.

Solnit invokes the Etruscan word saeculum to describe a person’s living memory and compare it with the longer-lasting legacy of a tree. Orwell described it in an essay on the original Vicar of Bray, who lived in the 16th century.

He planted a yew tree and played both sides in the religious wars of that time. “That fickleness let him survive and stay in place, like a tree, while many fell or fled,” Orwell wrote.

“Yet, after this lapse of time, all that is left is a comic song and a beautiful tree, which … must surely have outweighed any bad effects which he produced by his political Quislingism.”

The yew tree planted at St Michael’s Church, Bray. Photo: Rob Neild

Solnit uses this as an example of Orwell’s ability to move easily from the particular to generalities, from the major to the minor – from, say, a tree to universal questions of redemption and legacies.

She visits the Orwells’ cottage at Wallington and inspects the Albertine roses planted in 1936 as a saeculum for the couple, who married that year before going to Spain. Later, they lived in London during the war years, when both were employed in well-paying jobs.

In 1945, they adopted a son, Richard Blair, but Eileen dies during surgery, while Orwell is plagued by his respiratory ailments, which are exacerbated by London’s notorious air pollution. He moves to the island of Jura in the Inner Hebrides, where with the help of family and others he cultivates a large farm in one of Scotland’s most inhospitable climates.

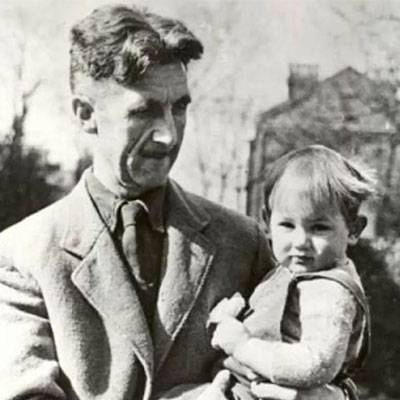

George Orwell with Richard in the late 1940s.

By now famous and commercially successful, Orwell entered the final stage of his life. His work pulled him back to London from time to time, despite the effect on his health, but he managed to complete Nineteen Eighty-Four on Jura. It was published in 1949 to much acclaim just months before his death from TB in a London hospital, aged just 46.

Shortly before, he had remarried, to Sonia Brownell, one of many intellectual women he had wooed. She guarded his literary legacy and ensured a stable upbringing for Richard. In the spirit of saeculum, Orwell’s work and ideas live on from an age that is no longer in most people’s living memory.

Yet his opposition to authoritarianism and totalitarianism are as relevant as ever, as is his analysis of how language and politics is corrupted by lies and propaganda. Underlying these is the right to privacy and the enjoyment of life without intrusion.

Gardening requires and rewards hard work. Orwell viewed life as not about achieving permanent happiness but was to be valued for its moments of delight, even rapture. This book is full of ideas and one that Orwell, as a connoisseur of prickly flowers, would have appreciated.

Orwell’s Roses, by Rebecca Solnit (Granta).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.