The Borgias of the modern world

A warning against the decision-making powers of AI.

The Hour of the Predator, by Giuliano da Empoli, translated from the French by Sam Taylor.

A warning against the decision-making powers of AI.

The Hour of the Predator, by Giuliano da Empoli, translated from the French by Sam Taylor.

The Nobel Prize for Economics is eagerly awaited each year as a sign of the profession’s latest trends. After several wokish years, the pendulum at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has swung decisively to the right.

The issue is economic growth and its absence in most of the world’s advanced societies, including New Zealand. The three recipients are intellectual descendants of Joseph Schumpeter, a product of the Vienna Circle and famous for his conception of ‘creative destruction’.

The Dutch-born American-Israeli economic historian Joel Mokyr, of Northwestern University in Illinois, has published books on subjects as varied as the origins of the knowledge economy, the Industrial Revolution, the Irish Famine, and working from home. His seminal work is A Culture of Growth (2016), and he won a half-share of the 11 million Swedish kronor ($2m) prize.

The other half was shared by French-born Philippe Aghion of the London School of Economics and the Collège de France (Insead), and a Canadian, Peter Howitt, of Brown University, Rhode Island. They were recognised for turning Schumpeter’s insights into the mathematical language of modern economics. (I reviewed Aghion’s The Power of Creative Destruction here in 2021.)

Schumpeter wrote Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy in 1942 when most of the world was at war and socialism was the fashionable belief of the intellectual class. Schumpeter acknowledged he wrote it in an “atmosphere of hostility” toward capitalism and that condemning it was “almost a requirement of the etiquette of discussion”. The book was reissued in 2009 with the apologetic title of Can Capitalism Survive?

Nobel economics prize co-winner Joel Mokyr.

Today, capitalism is again on the defensive, and the Swedish academy was no doubt thinking of US President Donald Trump’s response to low growth by replacing the global free trading system with protectionist tariffs.

Mokyr’s work on the Industrial Revolution, which ushered in the world’s biggest advance in economic growth, focused on its cultural aspect. One commentator, Mitchell Palmer – an economist at the Adam Smith Institute in London and policy adviser to Act Party leader David Seymour – described this as a “delightful cocktail ... Uniquely in human history, it combined bright scientists, curious businessmen and a skilled workforce with a society that was tolerant of – and, indeed, often positively giddy for – change and improvement”.

Joseph Schumpeter.

Aghion and Howitt provided evidence that this theory still holds today. “Those sectors where firms enter and exit often, and workers gain and lose jobs often, are the sectors with the fastest productivity growth. They also persuasively link America’s decline in dynamism to her decline in growth,” Palmer stated.

Does this apply to New Zealand? The Nobel trio emphasise the need for change and Schumpeter’s original dictum. Sadly, this is missing in New Zealand. Most economists are employed in bastions opposed to change – the trading banks and large-scale enterprises, as well as the universities and the public service.

A former colleague at the National Business Review, Barrie Saunders, picks up this theme in a blog, ‘Why is NZ stuck in the slow lane?’ His observations are based on his experience as a lobbyist and four recent months of living in Australia, which has some of the same problems.

Unlike Saunders, the Nobel trio are not an easy read. For lighter relief, I turned to The Hour of the Predator, by Swiss-Italian journalist and political adviser Giuliano da Empoli. He wrote The Wizard of the Kremlin, which was a bestseller in France, where he lives. A movie version was recently released starring Jude Law as Vladimir Putin.

Da Empoli’s new book is a series of vignettes, most of them personal, ranging from a talk by Henry Kissinger in Rome (1995), an Obama Foundation launch dinner in Chicago (2017), another Kissinger seminar with AI (artificial intelligence) gurus Sam Altman (OpenAI) and Demis Hassabis (DeepMind) in Lisbon (2023), to a demonstration of Meta’s virtual reality glasses in Montréal (2024).

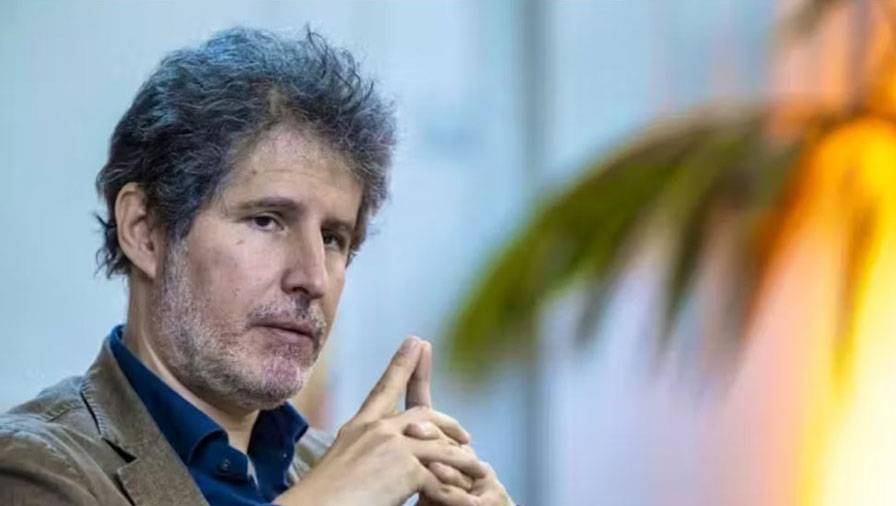

Giuliano da Empoli.

Also included are an encounter with Google’s Eric Schmidt and the AfD (Germany’s far-right party) in Berlin, leaders’ week at the United Nations, and Saudi Arabia’s strongman MBS (Mohammed bin Salman) locking up his rivals in a luxury hotel, all in 2024.

A sidelight is a scientific project to discover the remains of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Battle of Anghiari under 16th-century artist Giorgio Vasari’s frescoes in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. This prompts da Empoli to reflect on the changing nature of war.

Peter Paul Rubens’ copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Battle of Anghiari’ (1603).

The Battle of Anghiari lasted for one day in 1440 and was between the forces of Milan and the league of some Italian states led by the Republic of Florence. It was noted for its participants fighting only for the money, and the lack of casualties.

“These days, attack is cheaper than defence,” Da Empoli observes, given it can be waged with cheap drones and cyberwarfare. Da Vinci did not complete his work, and a few years later, its sponsor, Florence, ceased to exist as a political entity.

Such anecdotes are spread throughout The Hour of the Predator. Although Da Empoli fails to land his prey, he does have some interesting political insights.

These come in threes. First, the three types of political TV shows: the West Wing model of virtuous, competent types; the law of survival in House of Cards; and the comedy of errors, depicted in The Thick of It and Veep. Da Empoli calculates the first two make up 10% and 20% respectively, with the remaining 70% filling the last category.

Kevin Spacey in House of Cards. (Source: Netflix).

Then comes former British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s three stages of leadership: the willing listener who needs knowledge; once acquired, listening stops; and, finally, listening starts again.

An Italian writing about politics cannot afford to ignore Machiavelli. MBS provides that in spades as a Borgia-style man of action asserting his control over Saudi Arabia.

“Men are either to be kindly treated or utterly crushed, since they can revenge lighter injuries, but not graver. Wherefore the injury we do to a man should be of a sort to leave no fear of reprisals,” Machiavelli wrote about seeing Cesare Borgia in action in 1502. MBS followed that to the letter at the Ritz-Carlton, Riyadh, some 500 years later.

But being slightly out of favour with such a leader may be the best place. In 1931, during Italy’s fascist period, Da Empoli finds a parallel in Curzio Malaparte being sacked as editor of La Stampa by Mussolini, its founder. Malaparte went into exile in France, where he wrote Technique of the Coup d’État, a study of how far-left and far-right parties overthrow liberal democracies, not by occupying parliament and the bureaucracy but by seizing its technical infrastructure, such as telecommunications, railways, power stations, and ports.

El Salvador’s ‘miracle’ president, Nayib Bukele.

At the United Nations in New York, Da Empoli gets a lesson in the art of politics from the ‘miracle’ president of El Salvador, ‘El Milagro’ Nayib Bukele, who has created a one-party democracy through his overwhelmingly popular move of locking up all his country’s criminals.

If Da Empoli has a common theme, it is that the monarchical despots of the past and present are little different from those who wield technological power in the West.

He recalls the fund-raising dinner for the Obama Foundation. Each table of guests had a ‘conversation facilitator’ in a celebration of wokeness that had no match for Silicon Valley’s pivot from the progressive side of politics to those of Trump. This was reinforced six years later in 2023, when Kissinger’s Illuminati of Nato and European Union leaders gathered in Lisbon to hear Altman and Hassabis.

“As they listened to these two popes of AI, it gradually dawned on the simple mortals in the audience – even if they were among the most powerful mortals on the planet – that there was not the slightest point of contact between their experience of life and the new world that was being laid out before their eyes,” Da Empoli recalls.

Although I enjoyed these first-hand experiences and the eclectic nature of them, I don’t share Da Empoli’s fears that the predators – the new Borgias – have allowed us to possess more information than ever before, but have made us less capable than ever before of predicting what will happen next.

It may be that Altman, Hassabis, and his ilk have no interest in history or philosophy by placing their faith in AI to make what Da Empoli calls “the crushing superiority of algorithms over the judgment of human politicians and CEOs”. But, if you see an inkling of truth in that, this is worth the quick read.

The Hour of the Predator, by Giuliano da Empoli, translated from the French by Sam Taylor (Pushkin Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.