Therapeutic thinkers: Getting along with others

ANALYSIS: A Wellington lawyer’s path from depression through philosophy.

Zest: Climbing From Depression to Philosophy, by Daniel Kalderimis.

ANALYSIS: A Wellington lawyer’s path from depression through philosophy.

Zest: Climbing From Depression to Philosophy, by Daniel Kalderimis.

A knowledge of philosophy is one of those nice-to-haves in anyone’s education. It also appears to be on the decline as an intellectual discipline with wide appeal.

Philosophy departments, where they exist, carry little weight in modern universities that have other priorities. I suspect, if you were introduced to a history of philosophy at university, you might struggle later in life to distinguish between Socrates and Plato.

My relationship with philosophy as an academic subject was restricted to the analytic kind that dominated the English-speaking world for the second half of the 20th century, though the Continentals had more appeal with existentialism and its offshoots.

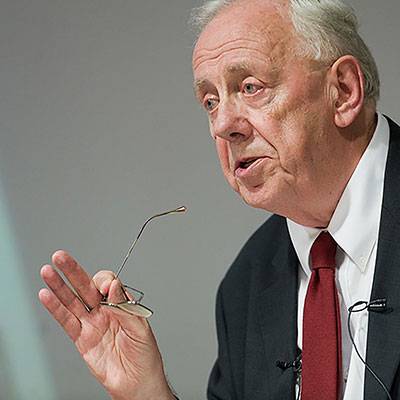

Emeritus professor Alasdair MacIntyre.

The recent death of Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, at 96, revived memories of his influence on my early thinking. His intellectual journey covered all the bases, from the failure of Marxism to solve society’s ills as well as those of liberalism and capitalism.

In the 1980s, he revived the ideas of Aristotle in the pursuit of a healthy society with studies in moral philosophy and ethics. MacIntyre ended up as a convert to Thomist Catholicism (based on Thomas Aquinas). Nathan Pinkoski, who translated Emile Perreau-Saussine’s French-language intellectual biography of MacIntyre, made this observation:

“By contending that pluralism was the sign of social fragmentation, not something to celebrate, and blaming the Enlightenment project for producing this shattered culture, MacIntyre overturned the tables in the temple of Anglophone postwar philosophy.”

Pinkoski went on to explain how MacIntyre’s embrace of Thomism led to his denunciation as a conservative and reactionary by his peers, who included American and Jewish-convert Martha Nussbaum. She is a pre-eminent exponent of virtue ethics, also in the tradition of Aristotle, and has popularised the use of literature in ethical thinking and the study of character.

Both MacIntyre and Nussbaum play a key role in a locally produced book by Wellington-based barrister and international dispute resolution expert Daniel Kalderimis KC. A lawyer writing about philosophy as a debating tool might be a common conception.

But Kalderimis embarked on a personal journey through philosophy and literature as therapy to overcome a period of depression in his 40s. A hard working litigation lawyer, happily married and with three daughters, he was the envy of many in the profession.

Daniel Kalderimis KC.

That was how he looked from the outside. Inside himself, it was much different. “I lost perspective and joy; my thoughts dismally, hopelessly, spiralling. I was in trouble. I needed and got psychological help,” he writes.

This mid-life crisis took him back to basics of the ancient Greek philosophers: the search for what really matters, “so that we do not waste (any more of) our precious time of what does not”.

Zest: Climbing From Depression to Philosophy takes its inspiration from Bertrand Russell’s The Conquest of Happiness (1930), in which he describes ‘zest’ as “the most universal and distinctive mark of happy men”.

Kalderimis describes zest as the opposite of depression and is due to aiming at things in the right way; a form of discipline so that “our values guide our beliefs, thoughts and feelings, which intersect to form habits of mind, which then find their way into our words and actions”.

It’s a take on an adage, variously attributed, though not accurately, to Mahatma Gandhi and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others: “Watch your thoughts, they become words; watch your words, they become actions.”

In his 20s at Victoria University, Kalderimis did not see religion – with its community, rituals, and habits – as the answer. Instead, he saw it in literature and poetry. He reproduces a letter he wrote in 1999 to Wellington poet Lauris Edmond. He appreciated one of her poems that enabled him to “feel a profound spirituality through my connection to people and places and my day-to-day experiences”.

Statue of Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot) in Nuneaton, England.

The letter quotes George Eliot’s Middlemarch as part of his “spiritual canon” for its understanding of people and the world. (I too studied Middlemarch at Victoria for the strength and variety of its characters but missed out on the philosophy.)

Best known as a novelist, Eliot was also an accomplished philosopher. Born Mary Ann (later Marian) Evans, after leaving university she joined the Westminster Review as editor.

She also translated some religious texts, including the work of 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza. This Amsterdam-based Sephardic Jew had been excommunicated from the exile community for his rationalism and radical views on spirituality. His seminal work, Ethics, written in dense Latin, made a deep impression on Evans before she embarked on her fiction career as Eliot.

Spinoza put human emotions at the centre of a philosophical system that explains how lives are shaped by relationships with other people. Kalderimis presents a lengthy analysis of Eliot’s work, with an emphasis on how the characters adapt to the demands from each other.

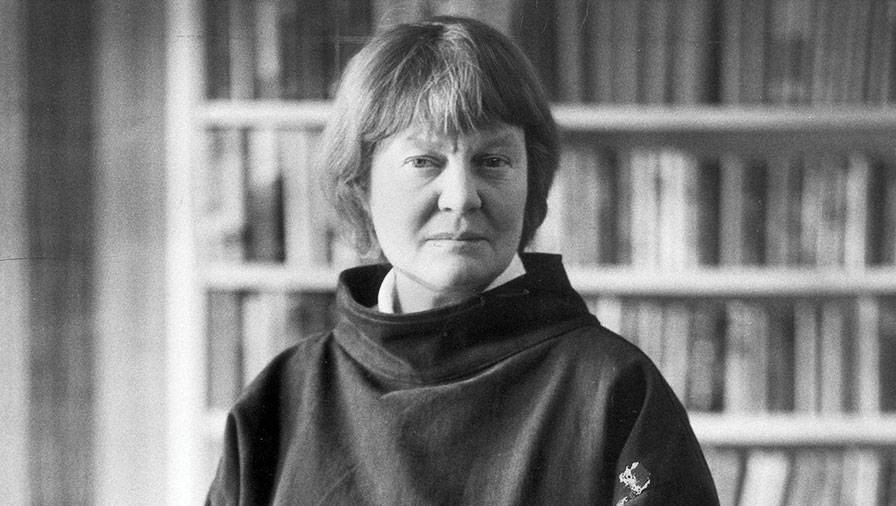

In Eliot’s footsteps came Iris Murdoch, another novelist-cum-philosopher, who was a leading virtue theorist at Oxford in the post-war period. Unlike Eliot, her philosophy was expressed directly as scholarship, as well as in her novels.

Her moral philosophy, like MacIntyre’s, pointed out the practical and spiritual limitations of the analytic school. Kalderimis singles out her lectures in The Sovereignty of Good (1970) and a novel, The Bell (1958).

He also mentions Murdoch was the first to draw the attention of English readers to French Marxist Jean-Paul Sartre’s writings on existentialism in Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (1953), published a year before the first of her two dozen or so novels, Under the Net.

Existentialism, as Kalderimis notes, was the starting point for many of his generation in a discussion of ethics. “It does not lay down rules to follow. It merely exposes the canvas of moral choice in front of us.”

This need to make life meaningful again goes back to the ancients. “What is new about existentialism is not then the quest for meaning, but its insistence on an individual’s ability – indeed responsibility – to create their own meaning for themselves.”

Novelist and philosopher Iris Murdoch.

In an allusion to modern-day technology, Kalderimis asserts Eliot and Murdoch function as a base operating system: “They do not, by themselves, give the right answers. But if you don’t install them, you will very likely get the wrong ones.

“Virtue ethics may signal the pathway in broad strokes, but it is a pathway that maps onto how people think, feel and act…”

Kalderimis finds existentialism lacking in solutions. Instead, he lands on the third of his triumvirate of female philosophers, Nussbaum, who has published prodigiously works on social justice, neo-Stoicism, and emotions. These include The Fragility of Goodness (1986), Love’s Knowledge (1990), and Anger and Forgiveness: Resentments, Generosity, Justice (2016), from which Kalderimis quotes extensively.

Zest is much more than a collection of quotes from high-quality thinkers. It ranges across a broad spectrum of philosophical approaches, from the Stoicism of the Greeks and Romans to Westernised Buddhism.

It also draws on examples from today’s mass media, such as popular music and Hollywood movies. Apart from those already mentioned, Kalderimis is also heavily influenced by American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s The Happiness Hypothesis (2006), which applies modern psychological research to ancient wisdom. Haidt has since produced bestsellers The Righteous Mind and The Anxious Generation, which have had a big impact on modern politics.

Even if you do not have a problem with depression, Kalderimis offers a stimulating intellectual trek that clears away the superfluous in any purposeful life. He has a suggested reading list of 19 titles plus a bibliography of 10 pages.

Zest: Climbing From Depression to Philosophy, by Daniel Kalderimis (Ugly Hill Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.