Something strange started happening to youth unemployment rates starting around December of 2008.

The global recession had started in earnest, but seemed to be nowhere in New Zealand’s unemployment statistics – at least among adults.

The adult unemployment rate hit 3.3% in 2008’s December quarter; not alarmingly higher than it had been in the prior few years.

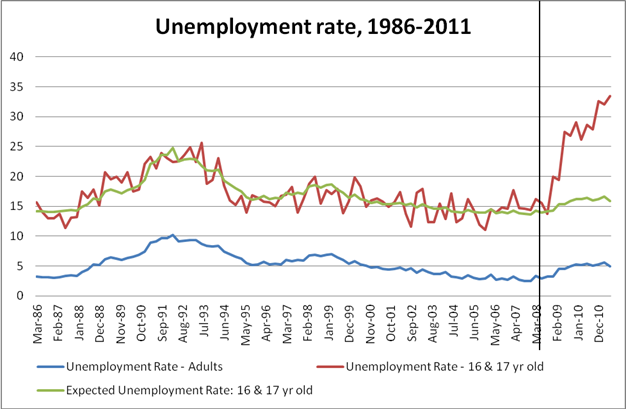

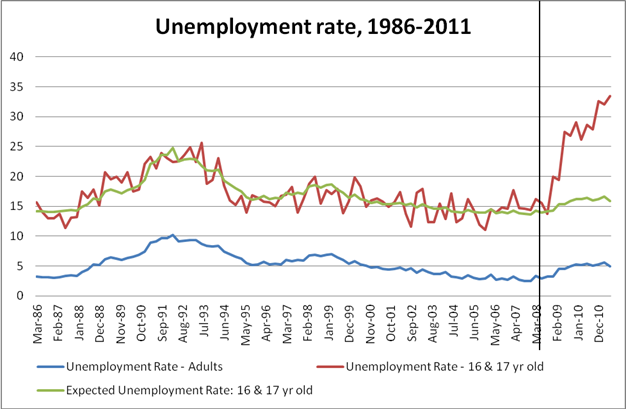

But the unemployment rate for 16 and 17 year olds, which had always tracked a fairly predictable but noisy path above the adult unemployment rate, instead took a jump.

Where we might have expected a youth unemployment rate around 14%, it instead touched 20%.

Two quarters later, when adult unemployment rates hit 4.5%, and we would have expected youth unemployment rates around 16%, the youth unemployment rate instead hit 27%.

Statistics New Zealand tracks unemployment by age going back to 1986. Before June 2009, youth unemployment rates had never exceeded 25%. They came closest in December 1992 when they hit 24.9%; the adult unemployment rate exceeded 9% from June 1991 until March 1993 and briefly topped 10%.

So it’s not surprising that youth unemployment outcomes were then so poor. But from June 2009 until June 2011, the last quarter for which I have the more finely-detailed age breakdowns,* the youth unemployment rate did not fall below 25% in any quarter while the adult unemployment rate did not exceed 5.4%.

Nine consecutive quarters’ youth unemployment outcomes higher than the highest previously recorded, at a time when adult unemployment rates were low relative to other downturns, seems something in need of explanation.

If we run the aggregate unemployment statistics through some fairly simple statistical models, we find that the relationship between adult and youth unemployment outcomes changed substantially in this recent period, although even simpler ocular least squares also tells us a lot. On average since June quarter 2008, youth unemployment rates have been about eight percentage points higher than we might have expected had things ticked along as they had previously.

Click to zoom. Black line March 2008 = Labour's abolition of youth rates.

What might have caused youth and adult unemployment outcomes to take such divergent paths? One explanation, and I think the correct one, is the Labour government’s abolition of the differential lower youth minimum wage effective April 2008.

Youth unemployment rates did not spike immediately afterwards, but neither would we have expected them to; employers are not likely to fire youths en masse with a change in the minimum wage, but they are likely to avoid hiring younger and riskier workers when more experienced and similarly-priced alternatives are available. And they’re also likely to stop creating the kinds of jobs that can usefully be done by lower-paid youths.

None of the statistical techniques I’ve used can let me say with certainty that the change in minimum wages caused the change in youth unemployment outcomes.

Something weird happened, with a timing that matches what we’d expect for the minimum wage changes and with an effect patterning across age cohorts that matches what we’d expect if it had been the changes in youth minimum wages. It’s always possible that something else caused the change, but it’s not easy to come up with a “something else” that either has the right timing, the right age targeting, or is big enough to plausibly have done the job.

National has recognised the problem; changes in the regulations around the lower youth “New Entrants” minimum wage are likely to make it a more feasible option for employers. But they also moved to increase the minimum wage by 50 cents effective in April.

Like introducing interest on student loan debt, bolder measures like ACT leader John Banks’ call for a reintroduction of a lower youth minimum wage seem likely to fall into John Key’s “good economics but bad politics” bucket; few of the kids who would get jobs under a lower youth minimum wage would thank National for it, but rather a few would blame him for lower wages. But it is a shame. It would be worthwhile investigating whether the minimum wage, for adults and youths, is the best way of supporting low income workers. Reasonable evidence suggests wage subsidies might do less harm than minimum wages to those they’re intended to help.

Dr Eric Crampton is Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Canterbury. He blogs at Offsetting Behaviour.

* Statistics New Zealand very helpfully provided updated figures just as this story went to press. In the most recent quarter, the unemployment rate for 16 and 17 year olds finally dropped to 24%.

Eric Crampton

Sat, 31 Mar 2012