Schumpeter’s ‘creative destruction’ could be key to Covid recovery

Book Review: French economists revive ideas from one of capitalism’s champions.

Book Review: French economists revive ideas from one of capitalism’s champions.

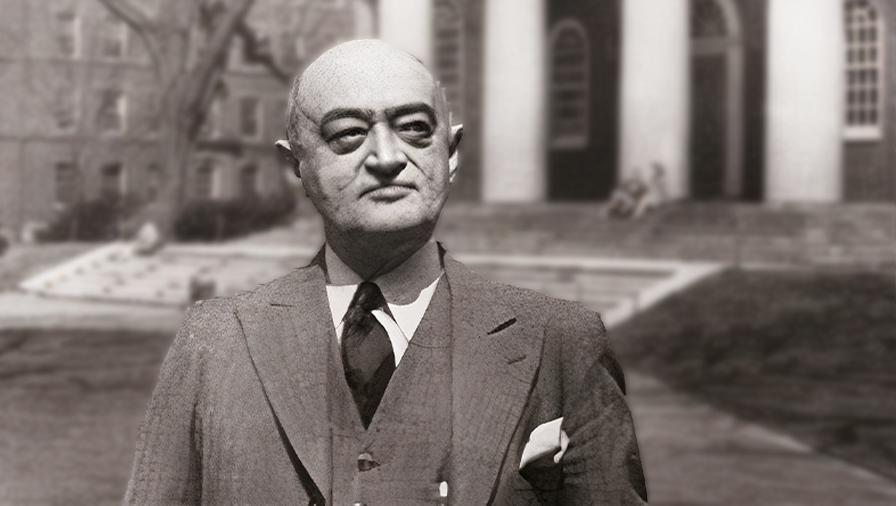

In economic jargon, the term ‘creative destruction’ is best known for highlighting capitalism as a system of winners and losers. It was coined by Joseph Schumpeter, a member of the Austrian school of economics that dominated free-market thinking in the 20th century.

Schumpeter, like many other leading intellectuals from central Europe, moved to the US in 1932; he died in 1950. His journey was not dissimilar to that of FA (Friedrich) Hayek, who fled to the UK in the 1930s, arriving in the US in 1962 and dying in 1992.

At last weekend’s Auckland Writers Festival, Wellington writer Danyl McLauchlan posted a picture of Hayek in a presentation on the most influential thinkers about morality. Most thought it was JM Keynes, last century’s most famous economist. No-one in the large audience recognised Hayek, one of capitalism’s leading advocates.

Hayek and Schumpeter were both defensive about capitalism, which among intellectuals was far less attractive than socialism and considered more akin to fascism. Schumpeter first wrote about creative destruction in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942) when most of the world was at war. It was recently reissued as Can Capitalism Survive? (2009).

In the prologue, he acknowledges the “atmosphere of hostility” to capitalism and that condemning it was “almost a requirement of the etiquette of discussion”.

In other words, it was not something you could discuss in polite conversation.

“Any other attitude is voted not only foolish but anti-social and is looked upon as an indication of immoral servitude,” Schumpeter added.

“On the one hand, the most obvious truths are simply put out of court a limine [at the outset]; on the other, the most obvious misstatements are borne with or applauded.”

In a footnote to his use of the legal term, Schumpeter observes another way of dealing with an obvious though uncomfortable truth is to sneer at its triviality.

Not one to miss an opportunity for sarcasm, he also noted a weakness in capitalism was that it produced a treasonous class of intellectuals who undermined the system from within, presumably in the hope socialism could smooth business cycles, remove the uncertainties of competition, and reduce friction between the state and the economy.

Exaggerated fears

Schumpeter’s fears about the future of capitalism proved exaggerated, as the neoliberalism of Hayek and his acolytes such as Milton Friedman eventually triumphed over Keynes in the second half of the 20th century.

But, in Schumpeterian fashion, neoliberalism stumbled in the global financial crisis and is taking a back seat as the Covid-19 pandemic fires up the ‘free money’ advocates of New Monetary Theory.

That surely won’t last and, in the wake of Thomas Piketty’s updating of capitalism’s shortcomings, some other French economists have revived creative destruction as the engine of growth in post-pandemic economics.

The Power of Creative Destruction is lead-authored by Philippe Aghion, a professor at the Collège de France, and was first published in French last year, a time when the pandemic was doing its worst to economies around the globe.

Governments closed industries overnight, throwing millions out of work, and in examples such as New Zealand opting not to revive them in the near future. Instead, workers were put on furlough payments or wage subsidies, forced to work from home, and faced the prospect of retraining in new roles.

Upside of disruption

Aghion and his colleagues recognise the upside of this disruption, just as global capitalism has lifted billions out of grinding poverty in just two centuries.

The starting point is 1820, when the Industrial Revolution in Britain broke several millennia of low economic growth. The most reliable historic measure of comparative economic performance – GDP per capita – is based on work done by Angus Maddison in The World Economy (2004) and other studies. Per capita GDP was close to subsistence level, estimated at $US400, in Europe from year zero up to 1000. In China, which was slightly more urbanised, it was $US450.

From 1000 to 1820, some long and sustained periods of growth occurred in two countries, Italy (1350-1420) and England in the 17th century. There were also slumps, but Aghion focuses on the 1820 “takeoff” when economic growth finally spelled the end to subsistence living.

The failure to achieve this earlier was widely attributed to demographics and agriculture. Land could only produce so much, and more people to share it meant no growth in GDP per capita. Improved technology fuelled population growth and therefore reduced per capita income – a phenomenon known as the Malthusian trap.

Aghion argues that this trap was avoided through education. Parents started to reduce their family size as each child required more resources to learn new skills. Fewer but more educated people led to rapid growth in GDP per capita.

Critical components

This historical evidence provides the pointers to the critical components of creative destruction outlined by Schumpeter: cumulative innovation as the driving force of growth; institutions that protect property rights, allowing the profits (capital) to be invested in further innovation; and competition that breaks down barriers to entry and thwarts governments from protecting incumbents.

These building blocks of innovation require more than just the ability to adapt to changing circumstances, as all societies did to varying degrees. It meant a distinction between theoretical and practical knowledge. Innovation results from knowing how to do something better.

But theoretical knowledge comes from knowing why – the scientific method, which did not exist in preindustrial societies.

For example, in chemistry, the formulas for compounds had been known for centuries but new compounds weren’t possible until they had been conceptualised. Mathematics and other scientific advances were possible when this knowledge could be spread through postal services and printing.

While this revolution was spreading throughout Europe, the home of many innovations, China, had banned navigation and resisted changes that could disrupt social stability. It took China two more centuries before it could catch up with the West.

Generating growth

The lessons for modern politicians and policymakers is to encourage change that generates growth. It is not necessarily instinctive. Monopolies owned by the state or other entities may appeal for their reliable rents but they are the least likely to herald change.

Aghion cites examples of technological innovations as the steam engine, lightbulb and microprocessors that took years before they contributed to productivity growth.

Some of this is due to the slow pickup in secondary innovation that creates real value from technological breakthroughs. This delayed the introduction of electricity and computers, largely due to a reluctance to replace existing methods.

One measure of creative destruction is the formation and extinction of businesses. Countries with a high rate of both, New Zealand included, is positive. Countries dominated by a few long-standing and large companies are less likely to experience high growth. One reason is that such companies can afford lobbyists to ensure their interests are protected by governments against newcomers.

Though little of the research quoted by Aghion and his colleagues is drawn from New Zealand, readers will be comforted by some obvious parallels. New Zealand’s top ranking in the World Bank’s Doing Business project is due to the relative low costs of an open market.

However, this can be constrained by the lack of market size, degree of concentration, and lack of flexibility in companies’ ability to change.

Recent government decisions are both positive and negative in this regard. Inquiries into competition issues in building supplies and grocery retailing could be valuable if they produce actual improvements rather than populist rhetoric.

But re-regulation of the labour market and mooted co-governance agreements in water and land management with organisations committed to long-term, rent-based ownership are likely to result in less productive work practices, stagnant investment and resistance to change.

Aghion’s research, based on 20 years of work at universities in the UK, US and Europe, covers many more issues than outlined above. These include inequality, the role of governments in promoting green technologies, the impact of creative destruction on health and happiness, the benefits of immigration on growth, and how capitalism can continue to achieve the objective of sustainable and equitable prosperity.

The Power of Creative Destruction: Economic upheaval and the wealth of nations, by Philippe Aghion, Céline Antonin and Simon Bunel. Translated by Jodie Cohen-Tanugi. (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press). Available on Amazon Kindle.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This content is supplied free to NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.