TelstraClear limitless weekend shines harsh spotlight on data caps, contention

Guest contributor Vikram Kumar looks at the economics behind data caps, "that pesky sword hanging over our head, shaping our Internet usage."

Guest contributor Vikram Kumar looks at the economics behind data caps, "that pesky sword hanging over our head, shaping our Internet usage."

LATEST: Some businesses seething, but TelstraClear says need for compo after weekend go-slow

Data caps, that pesky sword hanging over our head, shaping our Internet usage, are back in the spotlight.

Back in August 2010, I had mused in a blog post (Not speed alone) that while fibre will deliver faster last-mile broadband speeds for urban dwellers, many of these people are unable to take advantage of the broadband speed they already have.

People and businesses bring up data caps every time as a major hurdle.

Focusing on increasing speed without addressing data caps is, ultimately, self-defeating.

Since then, most ISPs have increased their data caps. As a percentage change, the increases have been large. For example, Telecom doubled the cap on all its smaller and medium sized plans. TelstraClear was a later comer to the party. Its is now cutting monthly costs which gives customers more data for the same monthly price. For example. $96 a month now gets 90GB instead of 60GB (a 50% increase).

Unmetered weekend

Starting from 6 pm on Friday, 2nd December, TelstraClear turned off usage metering for the weekend. Like a starter’s gun going off, customers unleashed their suppressed demand and hit the pipes. TelstraClear’s network barely managed to stand up to the assault, with cable download speeds plummeting to dial-up levels. Customers vented their frustration and there is a real danger that this experiment will lead to the conclusion that current data caps are critical to allow decent Internet speeds for all.

That is wrong. Why that is the wrong conclusion needs a longer explanation after some preliminary analysis.

Overseas comparisons

But before doing that, let’s take a quick look at the situation overseas.

Remember, with TelstraClear we can now get 90 GB per month for $96. The parent company, Telstra, in Australia provides (converting to New Zealand dollars) 200 GB for $90 and 500 GB for $115. So for our $96 we get about a third to a fourth of the Australians, even after TelstraClear’s current 50% increase.

Looking at the United States and taking Comcast as the most hard-nosed example of ISPs there aggressively applying data caps, our $96 per month gets us a package called Blast! with a download speed of 20 Mbps. Note that most ISPs in USA don’t have formal data caps and price Internet connections by download speed. However, Comcast has a 250GB ‘threshold’ which is in effect a data cap. Cross that and Comcast calls it “excessive use”. Customers who repeatedly cross the threshold apparently get a polite call. A customer who crosses the threshold 3 times in a 6 month period can have their account suspended for a year, i.e. Comcast’s policy is to boot out customers who regularly exceed 250 GB per month. That’s why the 250GB is for all practical purposes a data cap.

So, even in comparison with the most restrictive ISP in the United States and a 50% hike in our data caps, we get about a third for the same price.

I have deliberately compared TelstraClear with Comcast so that we get the lowest difference (one third). There are other comparisons which show that our data caps are up to a tenth of those overseas, particularly for the more typical data cap levels of 10-20 GB.

The hotel analogy

There is one more piece to look at before getting back to the (wrong) conclusion that the current data caps are critical to allow decent Internet speeds for all.

As an analogy, imagine if there was only one hotel in New Zealand. The owner only leases hotel rooms by the floor for 20 years to 4 big operators. Customers of these big operators lease a small number of rooms for a few years but they retail hotel beds by the night. So, the ‘retailers’ are leasing rooms (from the big operators) but selling hotel beds to their customers.

Now the retailers decided that they would have more beds than rooms they lease and put in beds only in line with what they sold. That way the retailers can lease less rooms, keep their costs down, and maximise profits. Customers are also happy because the price of a bed night is lower than it would be if some beds remained unoccupied each night.

Periodically, as the overall demand for beds in New Zealand increases, the hotel owner adds a floor. Imagine that building costs are going down rapidly. The hotel owner will only add a floor just ahead of an increase in demand. In the meantime, the retailers juggle the number of beds and room leases while the 4 big operators continue to take a big cut of the money.

This is what is happening in the Internet access market, especially the international IP transit market. Keep in mind that something like 80% of our Internet content comes from overseas using international IP transit. It’s easy to see why the international IP transit market is therefore critical.

ISPs are the ‘retailers’ in this market. Retailers sell bed nights (data per month) to customers but buy rooms (bandwidth) from the 4 big operators in the monopoly hotel called Southern Cross Cable.

ISPs sell Internet access at sticker rates of “up to” a download speed of say 20 Mbps but are really selling data allowances. They do this confident in the knowledge that customers will use their Internet connection intermittently. So they buy much smaller upstream bandwidth per customer, say 64 kbps.

But this model is increasingly under threat. Customers now want to stream video or backup their data to the cloud. They want high quality video calling and (used to) share files with peers. All of these services use the full pipe and suffer from under-provisioning of backhaul and international IP transit.

Economics 101

If you prefer pictures over analogy, let’s draw some graphs to illustrate basic economics.

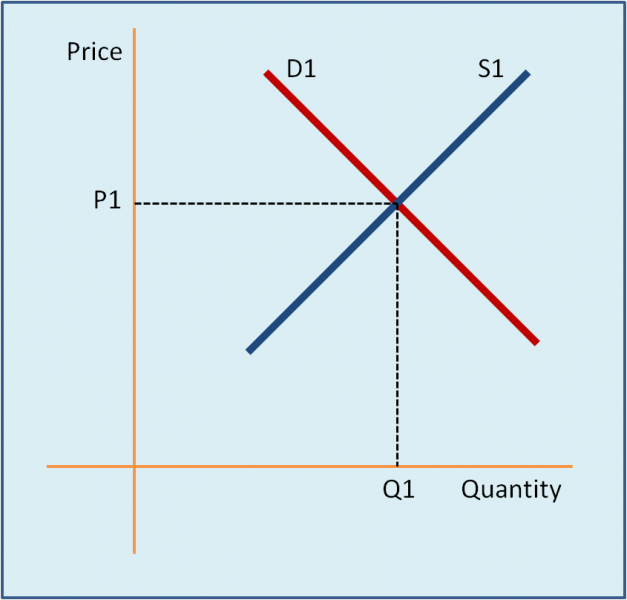

Figure 1: fully provisioned demand and supply

The graph above shows what Internet demand from people and businesses (D1) would look like in a free market where the last-mile speed is fully provisioned internationally. An equilibrium will be reached with the supply (S1) to determine the price (P1) and quantity of data (Q1).

The problem is that price P1 is too high for most people and businesses. At over a thousand dollars a month, it would simply put Internet connections out of reach for most. Also, a large part of the time the international bandwidth at an aggregate level would be idle and therefore wasted.

So ISPs purchase a fraction of the international IP transit bandwidth, called ‘contention’. The ratio varies widely across ISPs with a 1 Gbps pipe typically servicing between 1,000 and 5,000 retail connections of 10 Mbps.

Figure 2: shift in supply curve from contention

The impact of contention is to shift the supply curve to the right (S2). For the same data quantity Q1, price falls from P1 to P2. Done well, individual customers hardly notice the difference and both ISPs and customers are better off. Problems arise if ISPs are over aggressive, which shows up as congestion and customers complaining about a slow Internet connection.

However, New Zealand ISPs also intervene on the demand side by imposing data caps that suppresses demand. A contended international connection (supply side measure) does not stop customers from trying to download as much as they can from the limited bandwidth. Just a few customers using their contended Internet connection non-stop or ‘excessively’ would cause congestion for other customers. So ISPs limit the quantity of data an individual customer can download in a month to a very small fraction of what the contended Internet connection could theoretically download if used non-stop or ‘excessively’.

Figure 3: shift in demand curve from data caps

The result is that the demand curve shifts to the left (D2). The price remains at P2 but the demand is lower at Q2.

In summary, that’s the situation in New Zealand today - ISPs have delivered a lower price Internet connection by a combination of contention and suppressing customer demand.

Putting it together

It’s now time to go back and look at the question of the lessons from TelstraClear’s disastrous (for customers at least) unmetered weekend.

The conclusion that current data caps are critical to allow decent Internet speeds for all is, in my opinion, wrong. Given that New Zealand data caps are a fraction of what people and businesses get overseas for the same price we pay every month, continuing to suppress demand undermines our digital future.

Doling out periodic increases in data caps is not acceptable any more. Things need to change. Giving ultra fast speeds in the last mile actually makes the problem of data caps more acute.

So what’s the solution? Look at the graphs and it is evident that shifting the demand curve is only one option. The other one that hasn’t really been addressed by the industry and government is to shift the supply curve to the right. This allows higher data caps without an increase in retail prices.

One obvious answer is to increase supply by building another international cable. However, there are other things that can be done to shift the supply curve now, without waiting for another international cable.

I will address some possibilities in my next post. However, it is clear that one of the immediate steps is to let sunlight expose the murky international IP transit market.

Vikram Kumar is chief executive of InternetNZ.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.