NPR, which has only been around since the 1970s, has transformed itself for the digital age. Its website NPR.org is a major news source and each show attracts millions of podcast plays each month.

The public radio-broadcasting model is

very different in the US. While NPR produces a lot of content, it broadcasts it through a national network of around 900 affiliate public radio stations. These stations, like KCRW in Los Angeles, which became my soundtrack as I drove around the city last month, pay NPR for the content.

They also effectively control NPR, sitting on its board and deciding strategy. This has interesting implications as NPR’s focus broadens from radio to multi-platform.

As a result of the fees it collects for programming, NPR receives only a small portion of its $180 million budget from the federal government. The federal funding is doled out through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which has a budget this year of US$446 million – for ALL radio ($69 million to local radio stations) and TV public broadcasting funding, including NPR’s TV equivalent, PBS.

That’s around US$1.40 per US citizen, a relatively tiny amount, but a figure that attracts intense scrutiny all the same. NPR has long been accused of having a “liberal bias”, though it did back the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Regularly attacked by Republicans, who want funding of public broadcasting scrapped, President Obama has repeatedly argued the importance of state-funded public broadcasting.

What ultimately keeps NPR going is those fees from member stations (over 50 per cent of NPR’s revenue), who in turn receive some state and federal funding, but also donations, grants, sponsorship and who run a limited form of advertising called “corporate underwriting”.

As beloved as NPR seems to be, that underwriting, which comes in the form of regular brief mentions of sponsors, does grate on lots of listeners. However, strict Federal Communications Commission regulations cover the type of ads that can be run, which prevent the sort of heavy-handed ads you get on commercial talkback radio.

NPR and affiliates also undertake pledge drives, typically twice a year, to raise small amounts of money from listeners, a move that is increasingly successful.

The relatively diluted level of federal funding has led some, such as Forbes writer Adam Thierer, to suggest that public broadcasting is ready to be weaned off public money entirely:

“In many ways, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which supports NPR and PBS, has the perfect business model for the age of information abundance. Philanthropic models — which rely on support for foundational benefactors, corporate underwriters, and individual donors — can help diversify the funding base at a time when traditional media business models — advertising support, subscriptions, and direct sales — are being strained.”

The situation here

Radio New Zealand, by most estimates, is the most popular radio station in the country with the largest share of radio in the 15+ audience category. Shows such as Morning Report, Saturday Morning with Kim Hill, Our Changing World and This Way Up, attract loyal audiences.

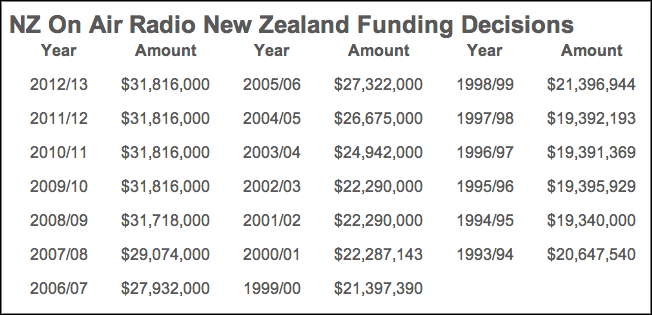

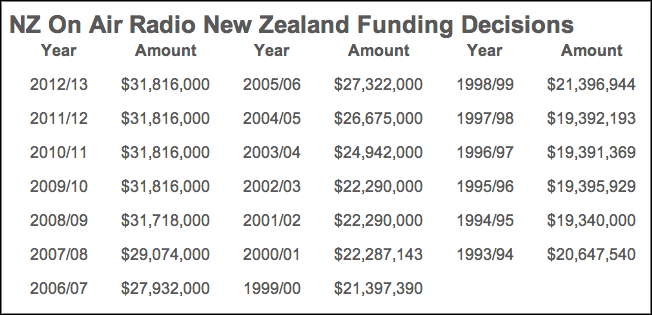

RNZ is 100% government funded (around $31.8 million a year, funding that has been frozen at that level for the last few years). That means no advertising, no pledge drives, no radio fees from affiliates. And RNZ has a much less complicated model as its two channels National and Concert FM are broadcast nationally.

RNZ’s static budget

But Radio New Zealand is under pressure to diversify its revenue, a task that RNZ board chair Richard Griffin has been handed by the government. Some RNZ board members are known to be uncomfortable with the prospect of pursuing sponsorship or advertising for RNZ shows.

The departure of RNZ chief executive Peter Cavanagh, who steps down later in the year after nine years running the broadcaster, is expected to remove a roadblock to the government’s plans to make RNZ generate its own revenue.

The issue of RNZ’s future came to a head in 2010 when broadcasting minister Jonathan Coleman set the board to work looking at potential funding sources.

A briefing paper for the minister’s meeting with RNZ revealed:

“Members of Boards who are not able or prepared to meet these expectations might need to move on and be replaced by members who can.”

The resulting public outcry was intense, with a Save Radio New Zealand Facebook page gathering 30,000 members.

The issue has been put on the back burner, but is likely to be reignited by the recruitment of a new CEO.

With a board tasked with diversifying funding away from taxpayer dollars, the new board-appointed CEO will likely have to be amenable to this aim.

So what are the options for RNZ?

Pledge drives: like NPR and its affiliates do, run twice yearly drives to attract donations from listeners. Advertise the fact that, since RNZ is a registered charity, donations are tax deductible. Given the support on the Save Radio New Zealand Facebook page, there’s likely to be some support for this.

Membership scheme: Taking the pledge drive a step further, RNZ could offer memberships that include things like VIP invites to broadcast events –RNZ currently does a number of these in science and the arts.

Build an endowment: The RNZ board could be put to work to secure large cheques from wealthy family trusts, individuals and companies. NPR’s endowment received a US$200 million boost in 2003 when wealthy philanthropist Joan B. Kroc left the massive bequest for the network. If RNZ could pull together $100 million, that, properly invested, could return $3 – 5 million a year tax free for operations.

Corporate underwriting: As with NPR, there’s likely to be tolerance for a low-level of corporate writing of RNZ shows and sponsored slots on its website. I could see this working for the station’s magazine-style shows, like Saturday Morning with Kim Hill and for Concert FM.

Music, books and merchandise: Receiving such a flood of artists through its doors for interviews and in-studio performances and with its rich heritage in classical music, RNZ could diversify into publishing music – digitally and on CD. The same could go for popular culture books, anthologies, biographies. Merchandise – RNZ cups, bags, t-shirts etc could also bring in some cash.

Grants: NPR and affiliates do quite well from universities and foundations that give money for specific shows, projects or documentary series. Such funding has to meet strict criteria and ensure complete editorial independence. I could see RNZ’s science show Our Changing World, for instance, being sponsored by the CRIs (indeed this once did happen) or the universities.

Online news: RNZ’s web presence is pretty good for finding and playing back audio but its online news coverage is minimalist. If Fairfax and APN put up pay walls this year, there could be an opportunity to beef up its online news content and offer some sort of advertising around it (in the same way that NPR has “brought to you by…” slots on its website.

Regardless of how RNZ makes up its future funding mix, the Government and RNZ management and board need to face up to the fact that the organisation has suffered through underinvestment. It’s online operations need the sort of revamp NPR.org received and an equipment overhaul is in order. So an increase from that baseline of $31 million will be required to keep the very high standards that RNZ staff have managed to maintain despite the budget freeze.

An opportunity to innovate

The call to diversity funding shouldn’t necessarily be feared – by RNZ or avid listeners.

The relatively low level of federal funding of NPR has allowed it to take a few risks, experiment with new technologies and formats.

For instance, the flagship show Wait, Wait… Don’t Tell Me is now being broadcast live to cinemas. Yes that’s right, the show that can be heard for free on the radio, is now pulling in paying audiences keen to be part of the live experience – albeit it remotely.

In 2005, NPR established NPR Labs to work on technology and innovations in the broadcasting space. NPR is rumoured to be in talks with automakers about a more integrated radio service, possibly available via satellite radio.

Chipping into the debate over RNZ’s future back in 2010-11 was South Pacific Pictures’ founder John Barnett, who suggested the broadcaster could adopt a “radio with pictures” format popular overseas, where cameras are installed in studios and programmes shown on TV too. He said RNZ could effectively become a fully-fledged multimedia broadcaster with reporters shooting footage on iPads.

The suggestion didn’t go down well, but the reality is that the technology enables it and with TVNZ looking less and less like a public broadcaster everyday, there may be a market for it that would only increase the potential for all those revenue-generating activities outlined above.

All things considered, RNZ is in an easier place when it comes to innovation. With NPR’s future to a large extent dictated by member stations who have an interest in maintaining the power of local radio, its efforts to diversify in the digital space will aways create friction.

As journalism academic and commentator Jeff Jarvis points out:

“A stronger NPR causes problems for the local stations. Because the local stations, there are some great ones around the nation, like WNYC here in New York that add a lot of value, but there a lot of stations that pretty much run records of NPR programming. And as the value of distribution sinks, which it will, the value of that station sinks.

“All these pressures on the local stations work in NPR’s benefit because NPR now can have its own distribution directly to the audience around the stations. “This American Life” gets huge amounts of money now, or good amounts of money, from people giving directly to the show because they have a podcast.”

Visiting NPR HQ

NPR’s Washington headquarters has a rundown look to it – that’s because the building is about to be vacated in favour of a brand new premises that will even feature new studios.

NPR staff, such as Anne Gudenkauf who has been with NPR for over 30 years and as science editor oversee’s NPR’s well-respected science coverage, are excited about the upcoming move.

The science team at NPR is around 30 strong, with reporters contributing broadcast stories across NPR shows as well as writing articles for the website. The move to digital means NPR’s science content has an international audience. The popular show Science Friday, is offered as a podcast and is one of the more popular science podcasts in the iTunes podcast directory.

But Gudenkauf told me that the same pressure on the local radio stations – the competition from digital, also threatens NPR unless it innovates.

That’s because anyone can package up content and distribute it via the internet in the same way that NPR’s text stories and podcasts are. It’s not hard then to run the sort of pledge drives NPR does, taking donations online. She says that’s what keeps NPR reporters on their toes, trying to create the best content possible in an online world awash with content of varying quality.

The goal has to be the same for RNZ which offers listeners a welcome relief from the brash punditry and advertising clatter of commercial radio and the sensationalism and shallowness of TV current affairs coverage.

But our much-loved broadcaster faces some major challenges ahead, ones which will require an innovative approach from the broadcaster’s new CEO.