Bright stars in Matariki short-story anthology

ANALYSIS: Paula Morris showcases the work of 27 Māori authors.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Paula Morris showcases the work of 27 Māori authors.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

When a US federal judge blocked the merger of two of America’s biggest book publishers, he effectively called an end to industry consolidation. Simon & Schuster was considered too big to be taken over by its larger rival Penguin Random House.

Instead, Simon & Schuster has been snapped up by private equity giant KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co), which will be viewed with trepidation. As part of Paramount Global, the Hollywood movie company, the publisher was a strong performer and an unlikely target for asset stripping.

Simon & Schuster headquarters in New York.

The publisher has a history of consolidation, having absorbed Scribner’s in 1994. But KKR may have got a bargain at US$1.6 billion, considerably less than Penguin Random House’s US$2.2b offer. Despite the symbiosis of Hollywood and publishing, Paramount had been shopping Simon & Schuster for three years after it was acquired in a merger with Sumner Redstone’s Viacom, the subject of Unscripted, reviewed here last April.

Hollywood is infatuated with publishing. Seldom a year passes without a movie such as Genius (2016), about the legendary Scribner’s editor Max Perkins and Thomas Wolfe in the 1930s. Perkins also launched the literary careers of F Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, while Scribner’s published Henry James, Edith Wharton, Kurt Vonnegut, Stephen King, Robert A Heinlein, and Don DeLillo.

Publishing and the movies have been buffeted by changes in technology if not content. If the KKR offer is successful, Simon & Schuster will join other media businesses, including a video game and software developer, a digital media company, a film production company, and other content production and creativity platforms.

KKR has said Simon & Schuster will retain its independence as a business that brought in revenue of US$1.2b in 2020 from best-selling authors such as King and Colleen Hoover as well as political titles by Bob Woodward, Donald Trump’s niece Mary L Trump, former vice-president Mike Pence, and John Bolton, Trump’s short-lived national security adviser.

In its writeup of the deal, the Wall Street Journal reported print book sales have declined since the Covid pandemic. To date, this year they are down 2.7%, to 365.6 million books, compared with the corresponding period in 2022.

Meanwhile, the UK’s Bookseller trade publication reports Rupert Murdoch’s HarperCollins division, the second-largest English language publisher, saw revenues drop 10% to US$2b in the year to June 30 due to lower consumer demand.

At the same time, Peter Kemp, chief fiction critic of Murdoch’s Sunday Times in London, published Retroland, a reader’s guide to fiction he has reviewed since 1970. Described as “the best-read man in Britain”, Kemp delivers his verdict on the big names in modern fiction as well as those who would aspire to be. His views may be controversial but at least he does a job that someone has to if the rest of us don’t want to waste their reading time.

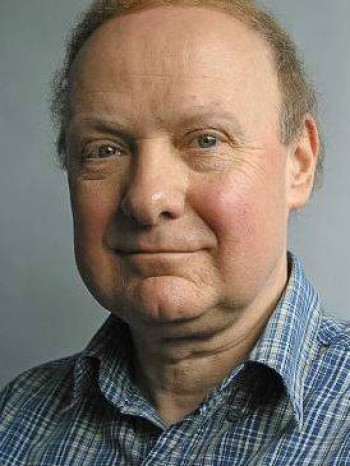

Sunday Times fiction critic Peter Kemp.

According to The Spectator, Kemp says fiction in English since the 1970s has displayed “a widespread and diverse enthralment with the past”. He divides this into four main categories: an “engrossment” with the political past, in particular the end of the British Empire; an engagement with the personal past, relating to childhood trauma and hidden lives; an obsession with historical fiction as a genre category; and the overwhelming presence of the literary past, leading to various kinds of sequels, prequels, reworkings, and imitations.

On individual authors, he is scathing about luminaries such as Salman Rushdie (“curiously inept at telling stories”, guilty of “artistic repetitiveness” and “emotionally wan and psychologically colourless”); Hilary Mantel (struggles with “over-copious historic documentation”); and Zadie Smith (tends to meander “as her whimsy takes her”).

Kemp’s unfavourable judgments are unlikely to be repeated on the local scene, where reviewers are generally positive about their writer-colleagues. The bestseller charts are dominated by a handful of highly praised writers, who are also the mainstay of well-attended book festivals.

It’s harder if you stray beyond these titles in search of a rewarding read. One path is the short story, which is usually the launching pad for a creative writing career. Although considered as less commercial than other forms, anthologies appeal to publishers and critics for their variety and range of contributor styles. They can provide milestones of a small country’s literary output but are not without controversy.

That happened in the early 1990s, when English publisher Faber commissioned CK Stead to compile a selection of contemporary South Pacific stories as part of a series of short fiction from around the world. On the brink of printing, Stead writes in the third volume of his memoirs, Vincent O’Sullivan pulled permission for one of his stories, followed by three Māori writers, Keri Hulme, Patricia Grace, and Witi Ihimaera, and Samoan Albert Wendt.

Faber couldn’t afford to let the project collapse, as Stead feared, and publication went ahead despite the absence of four of the South Pacific’s leading authors. Stead later learned that Ihimaera and Wendt thought he wasn’t suitable and led the revolt. Stead also revealed the 1981 Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse, edited by Allen Curnow, struck similar problems from a group of poets who thought the anthology was inadequate in its representation of younger writers.

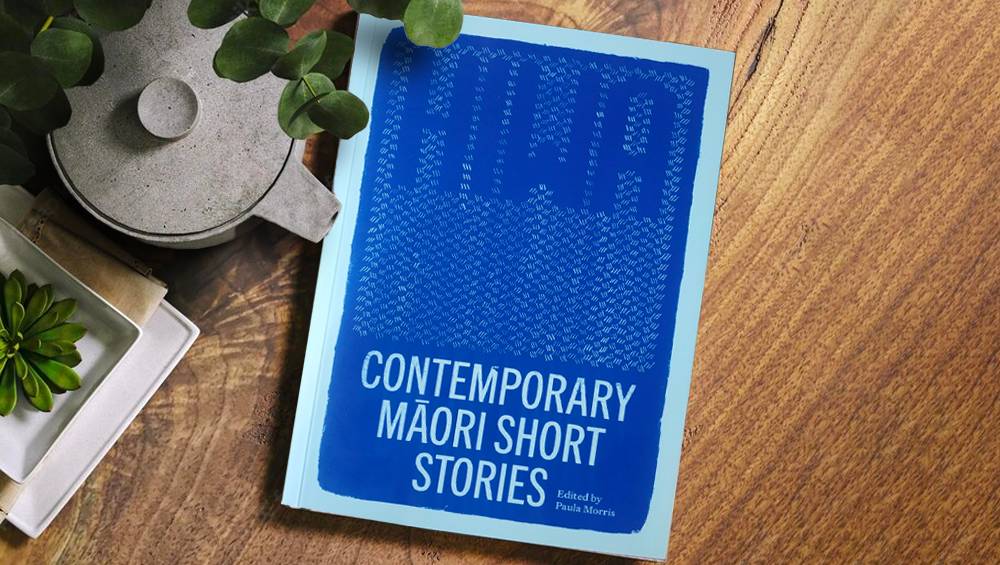

Paula Morris.

This sabotaging tactic was an early example of the ‘cancel culture’ at work but does not seem to have affected Paula Morris, whose mana in the literary world owes as much to her advocacy skills as her own considerable achievements as a writer. Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories is likely to be a milestone in New Zealand literature, which has a strong reputation in the genre going back to Katherine Mansfield early last century.

Other literary giants – such as Frank Sargeson, OE Middleton, and Maurice Duggan – also specialised in short fiction, while celebrated novelists – including Janet Frame, Maurice Shadbolt, and Maurice Gee – first came to attention with collections or in anthologies. Among contemporary writers, Owen Marshall stands out for his prodigious output and sales of short fiction titles.

Morris’s selection of 27 stories is based solely on Māori authorship and not the content. She says she has no “time for the identity border guards insisting that we must pass the Mātauranga Māori X-ray machine”. Contributors were not excluded “because their work does not enact a set of fixed expectations about the Māori experience and culture”. This does not seem to have troubled two of the writers mentioned above (Ihimaera and Grace) as they appear with solid pieces, both incidentally set in Europe.

Many of the other contributors reflect their overseas experience and their stories resonate with readers anywhere in the world. Each gets a brief biography and through interviews an opportunity to explain any context. This is valuable where the writers are not well known. All have been previously published, so the bibliographies are a good place to start for further exploration.

Whiti Ihimaera.

Ihimaera first wrote Der Traum (The Dream) after a visit to Berlin in 2018 and updated for this publication to include references to the invasion of the Capitol by Trump supporters in a story that probes differing world views. He also reveals he updated some of his earlier works for new editions. Grace’s The Kiss is about a Māori rugby player in Italy that also throws in references to artists Gustav Klimt, Auguste Rodin, and filmmaking.

Emma Hislop’s Scarce Objects is one of the few that provide a shock ending when the taking of kauri gum is revenged. Becky Manawatu’s Silly Buggers is an account of a drunken West Coast quiz night that illustrates the format at its best.

Anthony Lapwood’s The Ether of 1939 is at the speculative end of the spectrum, with a ghost story set in a radio factory that produces voices from the future, evoking cinematic images as well as making a telling point about changes in social attitudes toward sexuality. For contrast, Colleen Maria Lenihan describes a young Māori woman’s experience of working in seedy Tokyo strip bars.

Most of the contributors have graduated from creative writing courses (indeed, Morris teaches one), and the results are much like Kemp’s observations quoted above. They show a tendency to add clutter with references to popular culture and social anxieties rather than tell the story. Mental health, identity issues, gender confusion, workplace accidents, disinformation, single motherhood, domestic violence, and colonial oppression are all thrown into the mix.

While these are all serious issues, my personal demands in a short story are more targeted. As Morris says in her introduction: “Short stories are the wily messengers of fiction, shooting potent darts around the universe and through the centuries.” Incidentally, Hiwa is the ninth star of Matariki, signifying vigorous growth and dream of the year ahead.

Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories, edited by Paula Morris with Darryn Joseph as consulting editor (Auckland University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.