Creator and curator: An artistic journey in letters

A lifetime’s correspondence between Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

A lifetime’s correspondence between Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

The short intellectual history of New Zealand describes the 1950s as a decade of “dread conformity”. This mood was captured by Bill Pearson, whose lengthy essay The Fretful Sleepers was judged in 1960 with one other by Robert Chapman as the best non-fiction pieces published in Landfall to that date.

The Dunedin-produced Landfall was by far the leading literary publication of its time and not notably political. But Pearson, whose main work of fiction was Coal Flat (1963), reflected the dominant intellectual role of socialism in a decade when a conservative alliance between rural interests and city merchants controlled the Government.

Pearson was in London on post-graduate doctoral study in English literature and, from afar, judged the population as complaisant about the loss of constitutional freedoms under the National Government’s actions against striking watersiders during the Korean War.

Peter Simpson.

He worried about the appeal of an authoritarian state: “Fascism has long been a danger potential in New Zealand,” he wrote in The Fretful Sleepers. “In New Zealand, the ground is already prepared, in these conditions: a docile, sleepy electorate, veneration of war-heroes, willingness to persecute those who don’t conform, gullibility in the face of headlines and radio peptalks.”

Pearson challenged artists and intellectuals to throw off the “false consciousness” of colonialism. “Our job is to penetrate the torpor and, out of meaninglessness, make a pattern that means something…”

The founder-editor of Landfall, Charles Brasch, had no time for popular culture and his publication, although a quarterly, was a rich source of record of that period in all the arts, as well as town planning, architecture, art galleries, broadcasting, and universities.

All of this is described in Peter Simpson’s seminal Bloomsbury South, a history of the arts in Christchurch from 1933 to 1953. Like Pearson before him, Simpson was a Southerner (Simpson was born in Takaka and Pearson in Greymouth) and graduated from the then Canterbury University College. Both spent much of their teaching careers in the English department at the University of Auckland.

Simpson became a pre-eminent historian of the arts, with biographies of writers Ronald Hugh Morrieson and James K Baxter, as well as painters Leo Bensemann and Colin McCahon, the latter getting three large volumes. In politics, Simpson was a one-term Labour backbencher representing Lyttelton in the second term of the Lange-Palmer Government (1987-90).

In Bloomsbury South, Simpson quotes from a Landfall review in 1948 by ARD Fairburn of an exhibition by The Group, the country’s leading artistic collective. In one of those controversies that arise in close-knit communities, Fairburn attacked two of its luminaries, McCahon and Rita Angus, creating long-term feuds that Brasch only partly defused by assigning more temperate reviews of future shows by The Group.

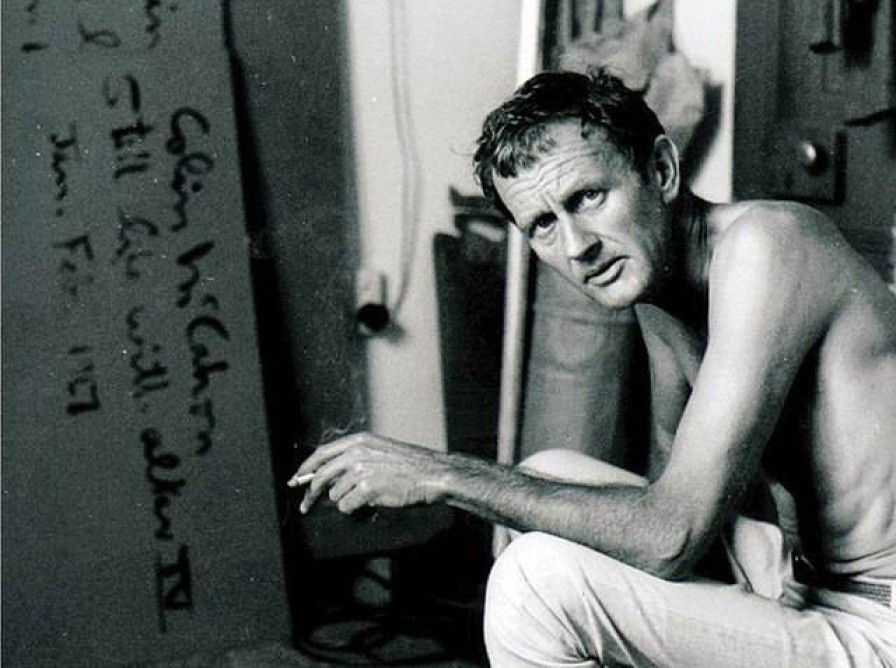

Colin McCahon.

Apart from being one of the country’s best-known poets, Fairburn was a lecturer in English and art history at the Elam School of Art. His deprecatory comments on McCahon’s “experimental cartoons” and lack of any “normal attribute of good painting” was not out of the ordinary.

In his latest book, Dear Colin, Dear Ron, a selection of letters between McCahon and life-long friend and supporter Ron O’Reilly, Simpson observes that McCahon’s “art was controversial from the start and often met with public censure and derogation”. Many years later, in 1962, another critic dissed McCahon’s work, forcing him to drop geometrical abstraction and return to the familiarity of landscape-related imagery with religious texts.

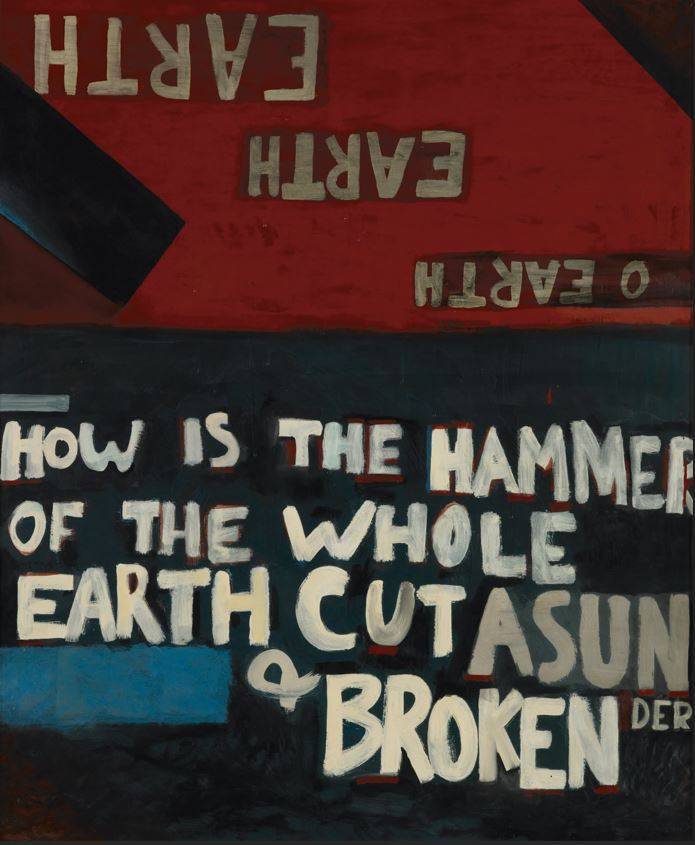

The Second Gate Series (Panel One), 1962. Te Papa.

The critic, JNK (Nelson Kenny), had questioned whether McCahon’s pre-occupation, in his Second Gate Series, with the danger of nuclear warfare in 1962 was an appropriate subject for painting. O’Reilly, then Christchurch City Librarian, publicly defended McCahon, but the criticism had struck home. A few years earlier, McCahon and his wife, fellow artist Anne Hamblett, had spent four months on a Carnegie fellowship in the US.

Ron O’Reilly.

It’s one of the few references to overt politics or bad reviews in a 500-page plus book that comprises 380 letters (some165,000 words) written between 1944 and 1981. While much of it contains mundane references to the staging of exhibitions and topics of mutual interest, they do not back up Pearson’s vision of New Zealand as cultural desert or a country likely to produce a Mussolini.

Timaru-born McCahon and O’Reilly, who was raised in Wellington and New Plymouth, first met in Dunedin in 1938 when both were students; McCahon at the Dunedin School of Art and O’Reilly studying philosophy at the University of Otago. They participated in Workers Education Association activities, such as staging The Insect Comedy, a satirical 1920s play by the brothers Josef and Karel Čapek.

Exempted from military service on health grounds, McCahon and Hamblett spent several years doing seasonal work in Nelson before moving to Christchurch in 1949. Meanwhile, O’Reilly and his first wife, Elizabeth Whittleston, had moved to Wellington where he qualified as a librarian.

The couples were briefly in the same city in 1952 when O’Reilly became Christchurch's City Librarian and before McCahon accepted a job at the Auckland City Art Gallery. The McCahons first lived in the artistic settlement of Titirangi, where their original house is today a museum. Alongside, is the McCahon House artists’ residency.

Throughout this period, until the mid-1960s, the McCahon-O’Reilly correspondence ranges from intellectual debates about the proof of God – McCahon was always a committed but unorthodox Christian and O’Reilly an atheistic socialist – through to the politics of The Group. McCahon was critical of it allowing too many mediocre painters into its membership.

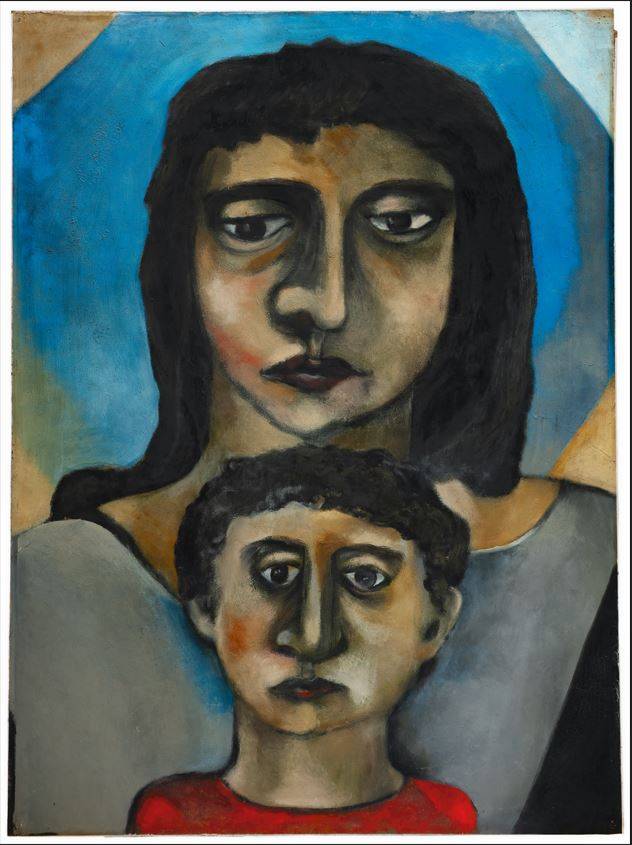

Madonna and Child, 1956. Auckland Art Gallery.

O’Reilly continued to champion McCahon’s work in exhibitions that were usually staged in public facilities in the days before dealers entered the scene. Not all of it was successful. One commissioned work, by international airline TEAL for the London-Christchurch air race in 1953, was rejected for display. It was put into storage and later sawn up accidentally for a packing case.

In a 1961 letter, McCahon reflected: “…[W]e all get older, more set in our ways, there is little change in what people have to paint … we tend to sleep comfortably on well-known beds.”

Further career moves in the mid-1960s resulted in O’Reilly, who had divorced and remarried (to Daphne Carruthers), moving back to Wellington as head of the National Library School after a two-year university posting in Nigeria. The rise of dealer galleries eased the burden on O’Reilly’s logistical activities if not his collection, while McCahon stepped up his output with exhibitions at Peter McLeavey in Wellington (1969 and 1971), Barry Lett in Auckland (1970), and Dawson’s Cellar in Dunedin (1971).

This enabled McCahon to retire from the Elam School of Art, where had worked since 1964, and focus on fulltime painting. O’Reilly also retired from the library school and wrote a highly personal essay on McCahon for a lifetime Survey at the Auckland City Art Gallery in 1972. (It’s published as an appendix along with contributions by Finn McCahon-Jones and Matthew O’Reilly.)

O’Reilly soon turned curation into a fulltime occupation as director of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery (and now Len Lye Centre) in New Plymouth from 1974-79. The correspondence enters its final stage as both suffer ill health. McCahon’s alcoholism affected his production in the late 1970s, by which time his fame had enabled him to move to a studio in Grey Lynn, an inner suburb, from Titirangi and Muriwai in West Auckland.

A final letter from O’Reilly in New Plymouth is sent in 1981. As usual, it relates to his voracious reading and viewings of recent exhibitions. He died in 1982, five years before McCahon, who had given up painting several years earlier.

Easter Morning, 1950. Auckland Art Gallery.

Grandson Finn McCahon-Jones writes of an initial reluctance to make the letters public. But he praises the moments when a practical friendship rises to direct and personal relationship “where ideas are aired, research discussed, influences revealed, and the daily grind recorded”.

Simpson’s transcription and editing of the handwritten correspondence are extensive and exhaustive. McCahon's total runs to several thousand. The O’Reilly family provided full access to his papers so that his role would be fully recognised for the first time.

The three chronological parts of the correspondence have more than 1500 footnotes, giving background on many people and places. This degree of scholarship doesn’t detract from the readability of a primary source that is unmatched in New Zealand art history. Both archives are now housed at Hocken Collections in Dunedin.

Correction: Peter Simpson's term as an MP was originally dated wrongly. The text has been updated. [April 4, 2024]

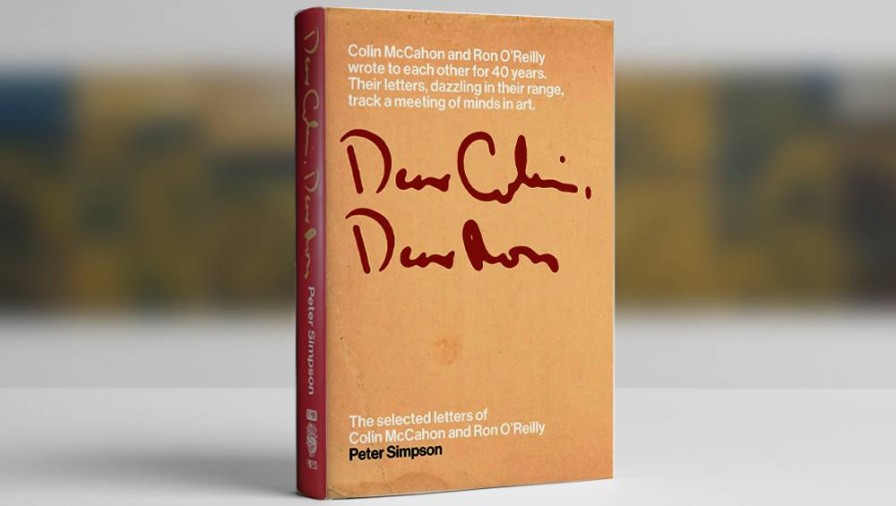

Dear Colin, Dear Ron: The selected letters of Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly, by Peter Simpson (Te Papa Press). Release date: April 11.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.