Five Eyes: The spy network that protects the West

A new history finds its successes far outweigh its failures.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

A new history finds its successes far outweigh its failures.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Depending on your political point of view, the Five Eyes alliance signals intelligence agencies linking the US and the UK with three British Commonwealth countries – Australia, Canada, and New Zealand – are a force for good or evil.

The evil side is readily available through the media, where Five Eyes is often presented as a bogeyman representing capitalism and whose enemy is the collective nirvana of socialism.

A newspaper report on a gathering of the Five Eyes in Queenstown last month breathlessly highlighted the “plainclothes Diplomatic Protection Service officers and undercover armed police” that were on hand. A US Department of Justice jet was identified at the airport.

The Left has long campaigned against Western security intelligence agencies, which were primarily established out of successful military operations during World War II. This is because they then turned their focus to communists and other sympathisers of the Soviet Union and, from 1949, China.

Since its inception, the Soviet Union has conducted a war of subversion against the West, even as it sided with the Allied powers that defeated Nazi Germany.

The emergence of the Cold War was foreshadowed by the West’s wartime political and military leaders when Stalin’s plans to seize control of Eastern Europe became obvious. This was confirmed by the theft of British and American nuclear secrets by Soviet agents.

Labour-led wartime governments in Australia and New Zealand were viewed as ‘soft on communism’ by the anti-communist hawks in Washington and London. Based on their wartime activity, the US and the UK signed a signals intelligence agreement in 1946, with room for Australia, Canada, and New Zealand to join in the future.

A year later, the Venona Project was launched to identify Soviet agents within government and military organisations. Among the first to be identified was Ian Milner, a New Zealander working for the Australian Department of External Affairs in Canberra. He defected to Czechoslovakia in 1950 after being tipped off by another KGB agent, James Hill, who was based at the Australian High Commission in London.

Australian Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley was briefed in London in 1948 on the Venona intercepts regarding Milner and Hill. The US had refused to pass on intelligence to the Australian government, forcing Chifley to set up an agency in 1949, the same year his government and Peter Fraser’s Labour one in New Zealand were voted out of power.

Conservative governments had no reluctance in urging their intelligence agencies to fight the Cold War in the early 1950s. This led to the official formation of the Five Eyes in 1956. The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (SIS) was also created that year, not long after the establishment of a forerunner to the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB).

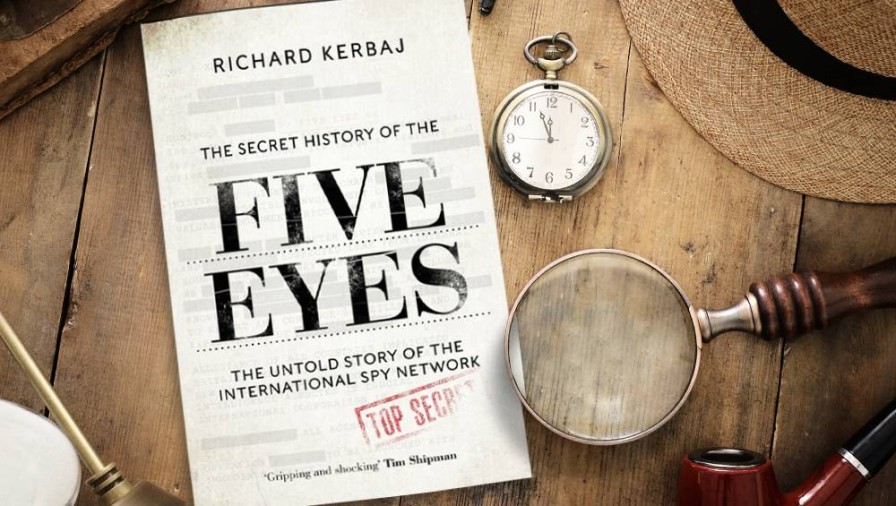

Richard Kerbaj.

This historical background is contained in The Secret History of the Five Eyes, by Richard Kerbaj, an Australian journalist who moved to London and worked for 10 years as the security correspondent for the Sunday Times. He then turned to documentary film making on espionage and jihadism. The word ‘secret’ may be hyperbolic but is justified by the fact that the existence of Five Eyes was not officially acknowledged until 2010 and no-one had previously written its history.

Of course, the existence of signals stations to collect all forms of communications was well known to activists supporting ‘peace’ policies such as nuclear disarmament, opposition to the war in Vietnam, and other examples of Western ‘imperialism’. These were of comfort to the main targets for surveillance, the Soviet Union and China.

Kerbaj’s account is a comprehensive history of the success and failures of the Five Eyes as an espionage organisation. His decade of research is based on archival material as well as interviews with a hundred or so of those involved, including former prime ministers Julia Gillard and Malcolm Turnbull in Australia, and David Cameron and Theresa May in the UK.

The Five Eyes’ signals data are supplemented by ‘human intelligence’, which is collected by agents on the ground. The Five Eyes ‘share’ data under their agreement while ‘humint’ agencies ‘exchange’ it, a much more limited process.

Their histories are told through many different cases – some well-known and others not so much – of individuals on both sides of the spying business. They range from an American home economics teacher who conceived Venona to a Kremlin spy, who was a German-speaking hairdresser in Dundee, Scotland.

Others are the Soviet defectors Igor Gouzenko in Canada, who first revealed Stalin’s nuclear ambitions; Oleg Penkovsky and the Cuban missile crisis; Oleg Lyalin, who revealed the extent of the Kremlin’s spy ring in the UK in 1971; and Vasili Mitrokhin, who did the same for the US and Australia in 1992.

The defection of Canberra-based diplomat Vladimir Petrov in 1954 warrants major treatment, as it was exploited for political gain in an election that split the Australian Labor Party and kept it out of power until 1972.

That year was a watershed for the intelligence agencies, as both Australia and New Zealand elected Labour governments that opposed covert activity against Salvador Allende’s left-wing regime in Chile and scaled down involvement in the Vietnam war. In Australia, police raided the offices of ASIO, Australia’s main intelligence agency.

By contrast, New Zealand’s National Government in 1982 gave signals intelligence to support the UK’s recapture of the Falkland Islands. That changed three years later when, because of New Zealand’s withdrawal from Anzus, the US may have withheld intelligence of French plans to sink the Rainbow Warrior.

Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior. Photo: Greenpeace – John Miller.

Later, in 2015, Nicky Hager revealed that New Zealand’s GCSB was monitoring China as its contribution to the network. China’s increasingly aggressive stance toward the West forced a rethink of Huawei as a supplier of cheap technology to 5G networks.

But it has not been all plain sailing for the Five Eyes partners. They constantly fall out over issues, particularly when one shows a lapse of security or a change in political policies. However, they closed ranks over the false allegations spread by presidential candidate Donald Trump that the UK’s GCHQ had wire-tapped his premises in New York before the 2014 election.

In one spectacular break with protocol, Australia’s High Commissioner in London, former foreign affairs minister Alexander Downer, directly passed on to US authorities a conversation he had with a boastful young Trump campaign operative who told him the Kremlin had hacked into Hillary Clinton’s emails.

Downer did not inform his own government first, not knowing this would become major political issue in the US and that Russian interference in US politics would pit Trump against intelligence agencies throughout his presidency. The informant was later jailed for 14 days for lying to the Mueller inquiry.

The US had its turn for an intelligence embarrassment when Edward Snowden revealed the full extent of the Five Eyes surveillance in documents released to the world media. In hindsight, Snowden’s bombshell revelations did not work in his favour, as the complicit media claimed at the time.

Edward Snowden.

“Snowden immediately became a hero to human rights and civil liberty activists, and a traitor to law enforcement and intelligence officials,” Kerbaj writes. Since then, Hong Kong, where Snowden first spoke to the media, has come under the thumb of Beijing and he remains in exile in Moscow, sheltered by a dictatorial government that is wreaking havoc against democratic Ukraine.

Surprisingly, the Western world has taken Snowden’s treason in its stride. Kerbaj quotes from an independent review by British lawyer David Anderson: “In the longer term, the Snowden revelations have not resulted in the rolling back of surveillance powers but in laws providing for improved transparency and oversight…”

Despite these ructions, the Five Eyes agreement is still not legally binding and remains built on a “framework of institutional and individual trust, secrecy, information assurance, and friendships”.

Naturally, the US dominates with its 100,000-plus intelligence workers, compared with the UK’s 16,5000, and a budget 18 times larger than the UK’s. The club is reluctant to let in new, non-Anglo members. “Most of [these] countries [are] … more motivated by what they could gain … rather than what they could offer in return,” Kerbaj observes.

He concludes that the Five Eyes has been a remarkable survivor, with its victories in the Cold War and against the terrorist threats from militant Islam. If anything, it has strengthened its purpose: “In a world where authoritarian regimes are constantly pushing the boundaries of cyber-hacking, misinformation, economic warfare, and the theft of intellectual property including scientific research, to gain tactical or strategic objectives or damage their adversaries.”

The Secret History of the Five Eyes, by Richard Kerbaj (Blink Publishing/Bonnier Books through Allen & Unwin).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.