Kirk’s ghost: Can Labour regain its mojo?

ANALYSIS: A ‘lost’ leader’s lessons for today’s social democrats.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

ANALYSIS: A ‘lost’ leader’s lessons for today’s social democrats.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

In every successful politician’s career there comes a time when those paid to observe them start to mention legacy. In recent times, two popular leaders, Sir John Key and Dame Jacinda Ardern, stepped down before that time arrived.

In another, more tragic, case Norman Kirk died in office after just 21 months as prime minister. Though widely mourned, historians now largely dismiss him. He received just passing mentions in the most-read modern histories, such as Michael King’s (2008), and the more academic Oxford (1992 and 2009) and Cambridge (2005) versions. However, Kirk has a generous three pages in Gordon McLauchlan’s updated Short History (2008). David Grant’s biography appeared in 2014.

Norman Kirk’s grave in Waimate Cemetery.

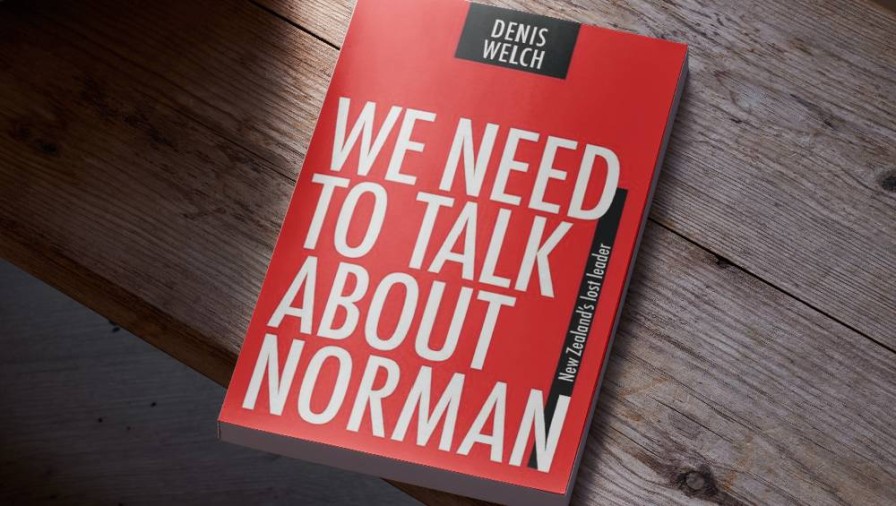

Kirk’s only physical memorials are a plaque over his grave in Waimate and some swimming pools. As Denis Welch notes in the just published We Need to Talk About Norman: “No statues, towers, government buildings, or institutions bear his name.”

As a fellow baby boomer, Welch began his writing career as journalist in the late 1960s, when Kirk was the charismatic leader of the opposition Labour Party. He was a first-term MP in the Labour government that was voted out of power in 1960. He became leader five years later, when the party became caught in the turmoil of opposition to the Vietnam war, nuclear weapons, and Springbok tours.

His victory in the 1972 election was a high point for left-wing causes, such as saving Lake Manapouri from dam builders, equal pay for women, recognising communist China, and an end to compulsory military training.

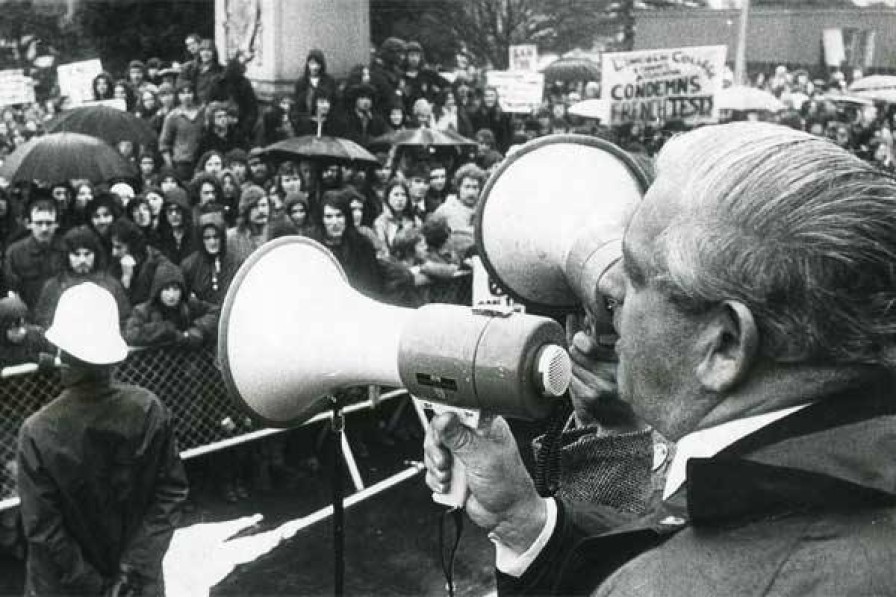

In its first six months, the third Labour government sent a frigate to protest against French nuclear testing at Mururoa, stopped a rugby tour by South Africa, and focused foreign policy on Asia rather than Europe.

Norman Kirk addresses an anti-French nuclear testing protest at Parliament (1972).

On the home front, the Government established a housing corporation, set up a rental appeal board, created the Waitangi Tribunal, introduced the domestic purposes benefit, established the ACC, restructured the DFC into a lender to business, and initiated a short-lived state superannuation scheme (later to be revived in a different form as KiwiSaver).

After Kirk’s death midway through its term, Labour lost its way in the areas where Kirk was weakest: economic strategy. In an outbreak of global inflation, his government failed at attempts to impose wage freezes and price controls.

“It did no fresh thinking about the structure of the economy, remaining content to operate in an orthodox social-democratic state-capitalist way,” Welch observes.

His memoir is a reminder and a call to action for social democrats, to revive those halcyon days when New Zealand had a working-class leader, who was self-educated, knew poverty at first hand, put more weight on moral values than monetary ones, and believed government was a public service, not a business.

Denis Welch.

Welch himself maintained his opposition to neoliberalism when Labour adopted some of it in its fourth turn at government in the 1980s. He defines capitalism as a “zero-sum game”. Apart from journalism, Welch stood as a candidate for the Values and Green parties.

My own impression of Kirk at that time was that he would have applauded some of the neoliberal reforms based on his autodidactic rather than academic knowledge. Above all, as a former small-town mayor, he was a man of action in a hurry and liked to get things done.

His closest colleagues were businessmen and he disliked militant unionists whose sole purpose was to disrupt ordinary people’s lives. According to Cybèle Locke’s biography of Bill Andersen, Kirk once considered using the army to break strikes, and uttered the famous words: “We’ve had a gutsful,” to describe Andersen’s constant strikes.

It’s speculation, but if Kirk had recognised and overcome his health problems – which Welch describes in never-told-before detail – he might have followed the examples of Australian Labor’s successful state and federal government politicians.

The recent failures of social democracy in Europe, reported by The Economist magazine, provide clues to why Ardern and her successor Chris Hipkins ignore the economic lessons of the past.

Optimists on the left have pointed to a leftward lurch by centrist free market politicians and experts in the US and UK. These converts typically see a greater role for governments in steering economies to better outcomes and less inequality.

At the same time, The Economist, which has also lurched to the centre in recent years, effectively buried social democracy as lacking competency in government and a credible vision. It noted some heavy intellectual hitters who have turned against predominant left-wing trends, best described as ‘woke’. For example, American socialist philosopher Susan Neiman has called for dropping identity politics and re-embracing universal rights.

Voters in recent European elections have solidly rejected social democratic parties, which The Economist calls “mushy and elitist”. Yet surveys show big majorities believe “the state should play a larger role in the regulation of the economy”. As recently as 2021, left-wing parties governed all four Nordic countries – former showcases for social democracy – as well as Germany, Spain, and Portugal.

Italy’s Prime Minister Giogia Meloni represents the antithesis of social democracy.

But in the following year, 2022, that changed dramatically. In France, the Socialists, already out of power, were all but wiped out. Hard-right parties now hold or share power in Italy, Sweden, Greece, and Finland, as well as in most of the former Soviet bloc.

Voters have either gone further left to more radical forms of socialism, including the Greens, or to parties of the right that are opposed to large-scale immigration and globalisation.

The Economist concludes that leftist parties offering more government spending face two problems. The first is that, with much higher inflation, interest rates, and debt, they no longer have fiscal room.

Second, conservative parties have increasingly embraced a bigger role for the state in economies. That makes it hard for leftist parties to stand out. But the right does not throw out the neoliberal baby with the bathwater.

One strategy for New Zealand, articulated by Max Harris, goes further left by resourcing iwi and hapū into collective enterprises, and targeting worker-friendly, decarbonised development. This industrial strategy would aim to build a more productive economy, with less dependence on housing.

What would a scaled-up industrial strategy look like? First, a National Investment Bank would provide lending and capacity-building. This could be a revamp of NZ Green Investment Finance, which received $300 million in Budget 2023. A National Infrastructure Bank was in National’s 2020 election manifesto.

Second, Harris advocates a more active approach to State-owned enterprises – especially the energy SOEs Genesis, Mercury, and Meridian.

Third, these three SOEs would return to public ownership to facilitate industrial direction-setting.

Welch’s preference is that Kirk’s economic ideas would have evolved into something more utopian: a New Zealand with no gross inequality; where education and healthcare at all levels are free and equal; employers and directors are not paid far more than their workers; trade unions help run companies; manufacturing is a strong part of the economy; no-one is begging on the street; and everyone is bilingual (at least knowing te reo).

It’s a tall order and politically aspirational. But competent execution and public approval would be essential.

While Kirk, in less than two years, could point to a substantial legacy, none of the above goals will be fulfilled by his successors of today. Hence the need for a book to remind them of their ‘lost’ leader.

We Need to Talk About Norman: New Zealand’s lost leader, by Denis Welch (Quentin Wilson Publishing).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.