The rusting curtain that divided Europe

OPINION: Historian’s journey finds Cold War borders still exist.

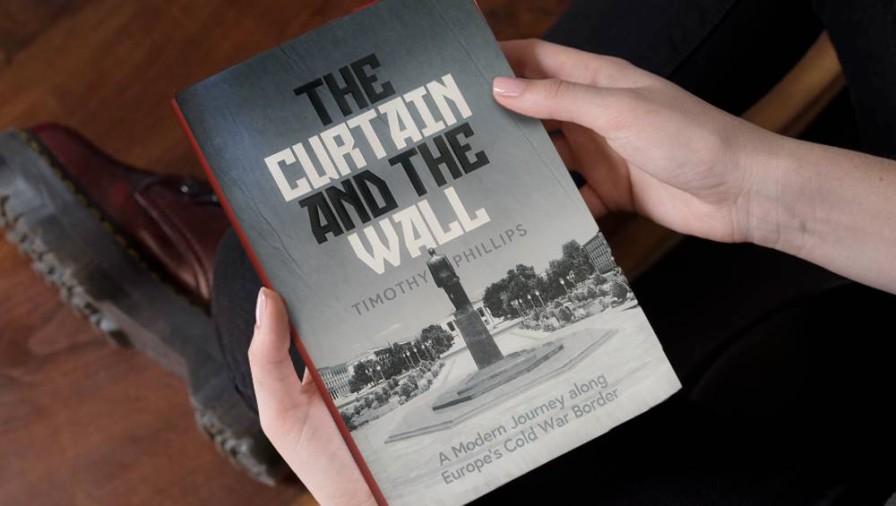

‘The Curtain and the Wall’ by Timothy Phillips.

OPINION: Historian’s journey finds Cold War borders still exist.

‘The Curtain and the Wall’ by Timothy Phillips.

Armchair travelling wrapped around a history lesson is a sweet spot for holiday reading. Topicality is also important, as well as limited opportunities for actual travel due to cost increases or other factors.

The Covid pandemic and Eastern Europe certainly fit that description as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has spurred publishers into a frenzy that is only outdone by Prince Harry’s autobiography.

Since the failure of communist regimes, starting in 1989, the breakup of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1991, this part of the world has produced a bonanza of books.

Among those about the lifting of borders that divided Europe for more than 40 years are Anne Applebaum’s Between East and West, primarily about Ukraine (reviewed here), and New Zealand-raised Kapka Kassabova’s Border (2017) set in the Balkans. Other authors to look out for are Neal Ascherson, Timothy Garton Ash, and Colin Thubron.

Latest to join the ranks is The Curtain and the Wall, by Timothy Phillips, described as a journey along Europe’s Cold War border. It is indexed with maps, graphics, source notes, and a select bibliography. Russian-speaking Phillips is a professional historian and has previously produced two books, The Secret Twenties, on intelligence agencies in the Jazz Age; and Beslan: The tragedy of School No. 1, about the 2004 siege in southern Russia where 333 people were killed, nearly half of them school children.

Timothy Phillips.

Phillips lists another travel book, Anthony Bailey’s Along the Edge of the Forest, as the inspiration for his own, more ambitious journey. Bailey (1933-2020), who is best known for his books on art history, published his account in 1983 when the Iron Curtain was rigorously enforced.

The Ukraine invasion in 2022 has created a new version, with Russia and Belarus now virtually sealed off from the West and countries such as Finland, the Baltic nations, and Poland policing their fortified borders to the east.

At the start of his journey, in Norway’s closest town to the Russian border, Kerkenes, Phillips found the Cold War had not ended. The locals still live in a state of Stockholm Syndrome, next door to Russia’s largest concentration of nuclear weapons.

Kerkenes would be the first Nato territory to be occupied by any Russian invasion – Finland not yet being in Nato – and its communications, including GPS, shut down, a practice the Russians carry out occasionally as a reminder.

Phillips meets the publisher of an English-language website, The Barents Observer, which keeps an independent eye on the region through external funding as both the Russian and Norwegian governments would prefer it closed.

Further south, in Finland, Phillips explores Porkkala, a peninsular to the west of Helsinki that was occupied by Russia from 1944-56 under a post-war agreement that put a 20-year moratorium on Finland joining Nato.

This was part of a neutralisation policy followed by Khrushchev that also saw the end of the Soviet occupation of Austria if it stayed out of a Western military alliance. President Putin made similar demands on Ukraine as a condition for not going ahead with his invasion.

Phillips makes only one crossing into Russia, to Vyborg, formerly Finland’s second-largest city (as Viipuri). It was annexed in 1947 and throughout the Cold War was ‘closed’ to outsiders due to its proximity to the border.

He next visits two islands in the Baltic Sea that had military significance. Gotland, just 130km from the Latvian coast, was heavily fortified by neutral Sweden during World II and during the Cold War as a landing place for refugees from the Soviet Union.

The other island, Bornholm in Denmark, was briefly occupied by the Red Army in 1945-46 and was also a target for refugees from Poland and the DDR during the Cold War. Phillips recounts how the entire southern Baltic coastline was closed to swimming, boating, and other recreational use under communist rule. At Priwall in northern Germany, nudists bathing in the West looked through barbed wire at the deserted beach on the other side.

Priwall’s nudist beach on the right; East Germany’s fortified border on the left.

The land border between the two German states was extensively mined and equipped with the world’s first automatic firing devices that indiscriminately shot bullets when triggered by any movements.

In the former Czechoslovakia, Phillips visits a town, Aš, that was joined by short railway line to a German one, Selb. The line was busy under Hitler’s ‘Greater Germany’ but the curtain fell between them after the communist coup in 1948.

A daring escape using the railway occurred in 1951 as a passenger train filled with refugees dashed through the barbed wire on a line that had been restricted to freight.

Phillips checks out a vast and hitherto secret missile complex at Bratislava (now the capital of Slovakia) near the Austrian border and not far from Vienna, where he spends time exploring its rich history of spying and international intrigue from the days of Harry Lime and The Third Man.

Another twin-town split in the curtain occurs at Gorizia in Slovenia, once part of Yugoslavia after it was seized from Mussolini’s Italy by Slovene partisans and the Italian population killed or expelled.

After 1947, a new town, Nova Gorica, was established on the Italian side of the border, which ran through the town square and cemetery. Nearby Trieste nearly suffered the same fate, with New Zealand armed forces having a role in the surrender of the German occupiers and resisting attempts by Tito’s Yugoslavs to bring it under communist control. Like Berlin and Vienna, Trieste was zoned as a ‘free’ territory from 1947-54, before being absorbed into Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia.

Although the southern end of the European Iron Curtain is generally recognised as ending at the Adriatic Sea, Phillips’ journey swings east to include Albania, which he describes under its communist dictator Enver Hoxha as imposing even more surveillance of its population than the DRR’s notorious Stasi.

“Prison and exile were norms of Albanian life to an extent unmatched in Europe after the mid-1950s,” he writes. Phillips visits the House of Leaves museum for a reminder of those days, as well as inspecting the ubiquitous concrete bunkers that numbered one for every four inhabitants.

Not all were created equal, a feature of socialist societies. The party elite’s version, known as Bunk’Art, was an enormous underground gated community built, of course, by Chinese. It is now open to the public, unlike those in Moscow or Beijing.

Entrance to the Bunk’Art Museum in Tirana, Albania.

Above ground, Hoxha sealed off a section of Tirana for his own Forbidden City, Blloku, and surrounded his country with a formidable iron curtain. The dictator died in 1985 and the first free elections in 1991 voted for a communist majority.

The socialist state was finally dissolved in 1998, leaving Albania with the unenviable reputation of being Europe’s poorest nation with a society of avenging clans, the highest incidence of wife-beating, and ruinous ponzi schemes.

Further east, and ending his journey, Phillips touches down in Nakhchivan, a landlocked exclave of Azerbaijan bordered by Armenia, Iran, and Turkey. It was part of the Soviet Union from 1920 and is home to the Aliyev clan, which also runs Azerbaijan.

The 500,000 citizens of Nakhchivan are sealed off from their neighbours, with whom they are often in conflict, as a living memorial of the Iron Curtain that in its past or new form in Ukraine puts up a border between people in the name of an ideology.

The Curtain and the Wall, by Timothy Phillips (Granta).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.