Battles over the past: One historian’s solution

Book Review: Jock Phillips spent a career telling the country’s many-sided story.

Book Review: Jock Phillips spent a career telling the country’s many-sided story.

The battle lines have been drawn over how New Zealand history should be taught in schools. On one side, fighting a rear-guard action, is Michael Bassett, whose reputation as an historian has produced as many critics as those of his political career. He is backed up by lay opinion-makers such as The New Zealand Initiative’s Roger Partridge and Chris Trotter’s Bowalley Road website.

All three see a danger in a curriculum based on the claim that, “Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand,” to quote the first of the Ministry of Education’s three “big ideas” for the curriculum. The other two are the continuing effects of colonisation, and the “exercise and effects of power”.

This describes the agenda of post-modernism and critical theory, which hold that society is based on an imbalance of racial, gender and other identities. As Partridge says: “Many aspects of New Zealand society owe little to colonisation and everything to human nature and human enterprise: familial love, romantic relationships, the enjoyment of art and culture, friendship, recreation, industry and trade, and even everyday work.”

Similarly, history cannot be described in the simple terms of power-wielding ‘victors’ and powerless ‘victims’. However, the revisionists see otherwise and have the upper hand.

A potential referee

A search for some sort of referee in this contest fell on Jock Phillips and his autobiography, Making History. It recounts his contribution as an academic and his more recent roles as the state’s chief historian and general editor of Te Ara, the official online encyclopedia.

As the first of the baby boomers, Phillips started his university studies in the late 1960s when revisionist history was in its infancy. Personally, our paths never crossed, except in one regard.

I spent a year at the University of Canterbury, where Phillips’s father, Neville, was a professor and headed a history department of exceptional talent. It was the same at Wellington’s Victoria, where I moved to and which Jock Phillips chose to attend.

History, English and philosophy departments in those days were stacked with world-recognised experts, who generally weren’t much interested in New Zealand subjects.

Canterbury, for example, had JJ Saunders on the Crusades, JGA Pocock on political philosophy, Sam Adshead on China, and WH Oliver, editor of the conservative quarterly Comment, a balance to the Marxist Monthly Review.

Victoria, too, had its share of world experts, particularly in English literature (Peter Munz) and philosophy (GE Hughes). But, like Auckland, it had a bigger focus on New Zealand history.

Student activism was at its height during the Vietnam war and Phillips admits his background didn’t attract him to the radical scene. But he “realised there was another world outside Fendalton and Christ’s College and Hawke’s Bay landholders”.

Like many of the country’s brightest students, Phillips went on to further his studies in the US (at Harvard), where he met and married English-born feminist Phillida Bunkle, later an Alliance MP. Radicalised by their American experience, both were keen to campaign against the 1970s provincialism they found in New Zealand.

Phillips’s targets included NZ Listener editor MH (Monte) Holcroft (who had temporarily come out of retirement after Alexander MacLeod’s controversial dismissal) and the doyen of New Zealand historians, Professor JC Beaglehole.

Phillips wrote: “The provincial mind sees culture as defined by the forms and traditions of a larger metropolis [London … and measures success] when the province finally makes a mark on the metropolitan culture.” This was prompted by Queen Elizabeth II honouring Beaglehole with a private audience and appointment to the Order of Merit.

Saying what others wouldn’t

The remarks stamped Phillips as someone prepared to say what others wouldn’t. He soon found favour with Holcroft’s successor, Ian Cross, and other cultural nationalists. Phillips gained his moniker ‘Jock’ because Cross considered the JOC initials from John Oliver Crompton as not blokey enough for a columnist – John being his actual first name.

The columns and monthly editorials raised Phillips’ public profile and his ambitions to explore the previously ignored cultural side of New Zealand history. He recognised from his American studies that frontier societies – the British settler nations of North America and Australasia – had similarities. They were created by people who had dreamed of making a better life.

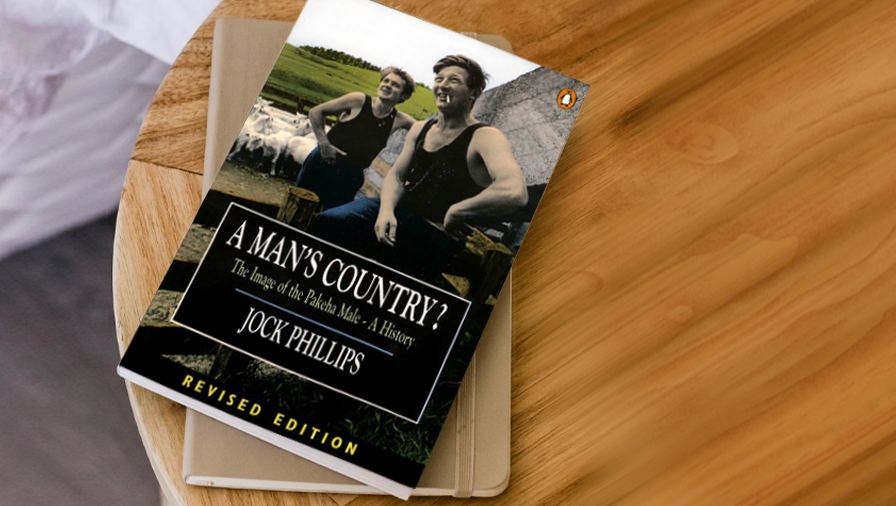

He also saw parallels in the rural male culture of 19th-century England and the places to where they had migrated. This study eventually produced his best-known book, A Man’s Country? (1987), in which the question mark in the title was an important qualifier. Phillips also expanded his research into previously untouched areas such as war memorials and oral history, much of it conducted in road trips.

This populist approach didn’t gel with traditional university teaching and he successfully campaigned to establish an independent institution to attract international scholars. This resulted in the Stout Research Centre of New Zealand Studies at VUW, a model for the later proliferation of centres of excellence in all universities.

In 1989, Phillips was tapped for the role of chief historian in the Historical Branch of the Department of Internal Affairs. He transformed it from a near-moribund state into a thriving producer of historical books on government and voluntary organisations.

His next task was a four-year stint creating exhibitions at the new Te Papa Tongarewa, where the cultural war over telling the country’s story was keenly fought at all levels.

Museum professionals and academic historians feared it would be more a theme park than a repository of the past. Some felt it would be politically correct, overly sympathetic to Māori and that non-Māori exhibits would be cynical and questioning. Others, from ethnic and other minorities, pressured for their needs as well.

Phillips noted the revival in Māori language and culture, the creation of the Treaty of Waitangi and protests had “induced a dangerous combination of guilt, defensiveness and anger among some Pākehā.”

Though he described it as a “battleground”, Phillips aimed for a unified New Zealand identity that included aspects of Māori, from the haka to the Air New Zealand koru. Māori elements were therefore placed in all parts of the exhibits.

The three main themes in the exhibits were the immigrant experience, its impact on the indigenous culture, and the projection of this shared experience back into the world.

“My hope was that this would invite debate and open up perceptions, not close them down,” he writes in Making History.

Digital encyclopedia

For Phillips, completing that task had given him many more ways to present history to the wider public. He was to expand on that, as the world entered the digital age, by joining the newly minted Ministry of Culture and Heritage, which had, at his urging, taken control of the former Historical Branch from Internal Affairs, while Archives New Zealand was spun off as a separate entity.

The History Group, as it became known, then embarked on the world’s first fully digitised encyclopedia, Te Ara, a project Phillips led from 2002 to 2012. It was committed to high standards, plain English and tight editing.

Today, in retirement, Phillips laments it has not become the living and constantly updated resource he intended. It would appear Te Ara could also become the world’s first fossilised online encyclopedia. Unlike Wikipedia, it does not include much new material such as Covid-19.

In addition, Phillips’s insistence on plain English is no longer a feature of the public service, which now uses the jargon of post-modernism and metaphysics on everything from the education curriculum to tourism policy statements.

Phillips’s own view is that the past must not be endorsed uncritically.

“Rather, to understand how the nation developed those myths is the first step in freeing the community from their dominance. … We cannot improve this society unless we understand what caused the pains and what brought about the pleasures of the past…”

He suggests the big questions any historian should tackle are:

The answers are worth knowing and the purpose of any history curriculum should help to deliver them.

Making History: A New Zealand story, by Jock Phillips (Auckland University Press)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This content is supplied free to NBR