Disaster politics: Why the world was slow to react

Book Review: Historian Niall Ferguson’s verdict on the Covid-19 pandemic and future threats.

Book Review: Historian Niall Ferguson’s verdict on the Covid-19 pandemic and future threats.

In January last year, the financial historian and commentator Niall Ferguson was the ultimate global traveller. He could even have been a super spreader.

He was flitting from city to city on at least three continents, while in between airports and hotels giving presentations and speeches related to his prolific output of books.

His punishing itinerary brought him to Auckland in October 2017 to promote his book The Square and the Tower, which was critical of weak government responses to the global financial crisis a decade earlier, and had pitted public networks (the square) against hierarchies (the tower).

Now, in the middle of another global crisis, he describes how somewhere between London, Dallas, San Francisco, Hong Kong, Taipei, Singapore, Zurich, San Francisco (again) and Fort Lauderdale he started to feel slightly unwell with a persistent cough.

He was at Davos at the end of January when he first spoke publicly about an epidemic in China and a week later wrote that it, “had a significant chance of becoming a global pandemic”.

But no-one was concerned about this at the World Economic Forum, where the main worries were environmental management, social justice and governance (ESG) and climate change. As this was occurring, “flights laden with infected people were leaving Wuhan for destinations all over the world,” he writes in Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe.

This event has become a bigger worry since the firming up of suspicions that the Wuhan Virology Centre, and not the nearby markets selling live animals, was the source of Covid-19, as mentioned in this column a few weeks ago.

Ferguson says: “I was regarded as eccentric by the majority of delegates” in calling for a need to “resist that strange fatalism that leads most of us not to cancel our travel plans and not to wear uncomfortable masks, even when a dangerous virus is spreading exponentially.”

He followed his own advice, hunkering down with his family in remote Montana and staying there for the rest of the year while he wrote Doom.

Plague year diary

Pandemics aren’t novel to historians and Ferguson’s weekly newspaper column became a diary of a plague year. His previous dozen or so books have contained references to the impact of disease on financial history, particularly the flu epidemic that followed World War One (The Pity of War and The War of the World).

Empire (2003) covered the impact of contagious diseases spread by European colonists into North and South America, the deadly toll of tropical diseases on British soldiers posted overseas.

Civilisation (2011) has an entire chapter on the role of modern medicine in controlling contagious diseases during Western settlement and rule, without glossing over the often-brutal methods to do it.

The ability of viruses to mutate is referred to in The Great Degeneration (2013), while The Square and the Tower has the insight that, “network structures are important as viruses in determining the speed and extent of a contagion”.

The purpose of Doom is to study the history of disasters, whether man-made or natural, through their impact on economics, society, culture, and politics. In doing so, he explores the background to predictions of the apocalypse, the predictability of catastrophes, medical science, and initial observations on the Covid-19 pandemic. It’s a mammoth read, running to nearly 500 pages.

The end time

Human visions of the apocalypse – the eschaton (from the Greek eskhatos) or ‘end time’ – feature in most of the world’s religions, including the oldest, Zoroastrianism. In each, destruction is the prelude to rebirth. But the timing of doomsday and the heralding of a new world is not certain, whether Judaic, Christian or Muslim.

Millennialism has arisen from Christianity in various sects, particularly in the 19th century, and has not disappeared in modern times. Some cults have committed mass suicide, while Lenin’s war against clericalism in Russia was viewed by peasants as the coming of the antichrist. German political theorist Eric Voegelin saw communism and Nazism as flawed interpretations of Christian utopianism.

More contemporary examples, identified by historian Richard Landes, include Salafi jihadism, radical environmentalism and fears of a nuclear holocaust, typified in the Doomsday Clock, which now covers climate change as well.

Ferguson quotes the young Swedish activist Greta Thunberg as espousing latter-day millennialism: “Around 2030, we will be in a position to set off an irreversible chain reaction beyond human control that will lead to the end of civilisation as we know it.” Thunberg also attended Davos in 2020.

Disaster prediction

If humans are susceptible to predictions of disaster, they are even worse at forecasting them. Ferguson delves into various theories of history, mainly based on cycles, to find some answers. These feature in both Western and Chinese intellectual life. Ferguson believes they are defective because they leave relatively little room for the effects of geographical, environmental, economic, cultural, technological, and political variables.

Historians of the ‘cliodynamics’ school come closest because they have built a large database on the rise and fall of empires and states dating back to the Neolithic period. In one example, this has linked the collapse of civilisations to the lack of the written word.

But, in general, Ferguson is suspicious of single explanations because of random events and the failure of, say, the US to decline in the recent past despite many forecasts. He even challenges claims that China will surpass the US due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

One notable target is Jared Diamond, the best-known author in this field, for his analysis of Easter Island. Diamond mostly blames its collapse on the environmental impact of its original inhabitants, while Ferguson prefers the alternative of mainly external factors, including slavery and foreign diseases, and that rats ate most of the vegetation when they arrived with settlers much later in 1200AD.

The age of science

Ferguson is in familiar territory when he describes the human reaction to disasters and the efforts of leaders and governments. In the case of epidemics and pandemics, the focus is usually on the pathogens’ impact on human populations.

But the magnitude of the impact is as much due to the scale of social networks and the states’ capacity to cope. Previously in history, lack of medical knowledge left communities defenceless; the bigger and more commercially integrated a society, the more it was likely to suffer a pandemic.

But as late as the 1950s, pandemics were common. That didn’t change until global cooperation, even during the Cold War, eradicated diseases such as TB, smallpox, and polio, while reducing malaria and much else through sanitation and vaccination.

This created complacency despite countless warnings that humanity’s most clear and present danger was a new pathogen.

The worst case was that it would occur in an authoritarian country, where the first response is a cover up, as occurred in the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Soviet Union. The breakout of Covid-19 in China is still not fully explained.

Initial response

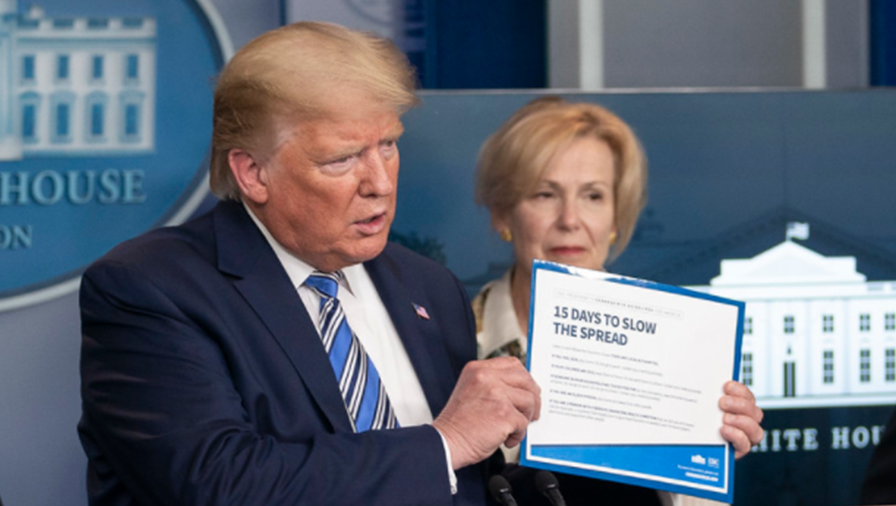

Ferguson is also critical of the response in the West, where some leaders at first played down the virus threat, and public health bureaucracies, with a few exceptions, were unprepared. He is also sceptical that catastrophes are correctly understood amid an outpouring of disinformation, bogus therapies, and conspiracy theories.

Simplistic assumptions in the mass media don’t escape his attention, either. This particularly applies to those who laid the blame for excess mortality in the US on former President Donald Trump’s confused response, as if history solely revolves around the actions of individuals.

In addition, “… there is a tendency throughout history, at times of acute social stress, for religious or quasi-religious ideological impulses to impede rational response,” Ferguson states.

One such phenomenon was the worldwide reaction to the police killing of George Floyd. However justified this was, to a brutal incident and systemic racism, the street marches posed a high risk to millions of unmasked demonstrators in the middle of a highly contagious respiratory disease outbreak.

On historical precedent, Ferguson thinks the next catastrophe is unlikely to be the one most expect, climate change. Instead, it could be a strain of antibiotic bubonic plague, a massive Russian-Chinese cyberattack on the West, or a breakthrough in nanotechnology or genetic engineering that has disastrous unintended consequences.

He concludes that lessons from the past point to social and political structures that emphasise resilience and what Nassim Taleb calls “antifragile”. They do not include panic solutions that involve calls for totalitarian rule or world government.

Doom: The politics of catastrophe, by Niall Ferguson (Allen Lane/Penguin). Available in Amazon Kindle.

Recommended reading: Antifragile, by Nassim Taleb (2012)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This content is supplied free to NBR