Dodgy dealing tale of two cities

Book Review: NBR’s first Shoeshine columnist turns his hand to fictional romp in business worlds of Auckland and Shanghai.

Book Review: NBR’s first Shoeshine columnist turns his hand to fictional romp in business worlds of Auckland and Shanghai.

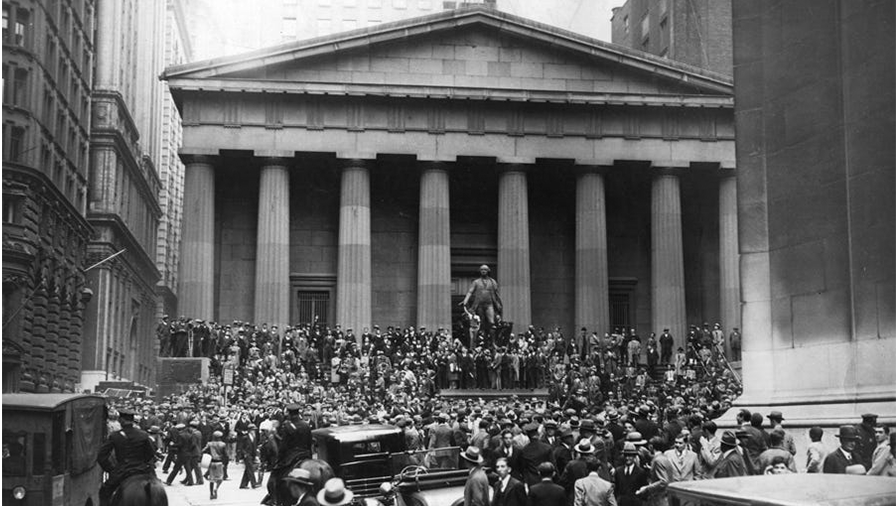

The Shoeshine column is the NBR’s longest-running feature. It was launched during the euphoria leading up to the October 1987 sharemarket crash, which hit New Zealand harder than most.

It was inspired by the legendary story about how, in the late summer of 1929, a shoeshine boy gave stock tips to Joseph Kennedy, a financier and father of John F Kennedy. Being a wise investor, Kennedy thought, “If shoeshine boys are giving stock tips, then it’s time to get out of the market.”

Kennedy made a killing by selling his stocks before Wall Street collapsed in October 1929, eventually leading to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The column’s first writer was Michael Wilson, who conceived the idea with then editor Jim Eagles in early 1987. I had worked with Wilson at Radio New Zealand and had earlier moved to NBR when it was based in Wellington. I recall he was keen on cricket and took as sceptical a view as Kennedy of the growth in share clubs, companies that listed on little more than hype, and the avalanche of financial shell-game deals.

Wilson switched to TV, at one time fronting NBR’s own business show on TVNZ’s short-lived Horizon network of regional channels. He spent a total of 27 years at TVNZ and TV3 before, in his words, he was “sacked for competence and being insufficiently Henry” – a reference to Paul, who had a morning show on TV3.

After a forced retirement, Wilson embarked on his lifelong dream of writing a novel. Three years after taking a year-long Master’s degree in creative writing at the University of Auckland he has achieved that dream.

It was not without its drama. He canned an earlier effort, describing it as a “chaotic mess.” Under the tutelage of Paula Morris, his writing became more disciplined and structured, helped by a rigorous workshopping schedule with other students on the course.

The class of 2017 has already produced a bestselling thriller (Rose Carlyle’s Girl in the Mirror) and three other well received novels (Amy McDaid’s Fake Baby, shortlisted in the 2020 Ockham Awards; Rosetta Allan’s Unreliable People; and PJ (Pip) McKay’s The Telling Time. A fourth graduate has a book due out in August.

The big prize

The top fiction prize in the Ockhams, officially the Jann Medlicott Acorn Award, is $57,000. Last year’s winner, Auē, by Westport-based Becky Manawatu, remains a bestseller. It is not unusual for a newcomer to win the award, particularly if they have already achieved some degree of commercial success.

Book awards first became a force in the early 1970s, after I finished my own literature studies at university. A small number of big names dominated the fiction category – Janet Frame, Maurice Gee, Witi Ihimaera, MK Joseph, Maurice Shadbolt, and CK Stead. Marilyn Duckworth won in 1984 after a 15-year gap from writing novels.

The Vietnam war and radical politics had a strong influence on the literary culture, which favoured poets more than writers of prose. In the early part of this century, Owen Marshall, Alan Duff and Lloyd Jones joined a strong cohort of male novelists. But they began to be eclipsed by a new generation of women, some of them emerging from Bill Manhire’s writing course at Victoria University.

In 2014, Eleanor Catton won the international Booker prize with The Luminaries, matching Keri Hulme’s The Bone People in 1985. Hulme quickly faded, in contrast to Elizabeth Knox, Patricia Grace, Charlotte Grimshaw and Fiona Kidman, among others.

Since 2007, 10 women have won the top fiction award against just two men (there was no prize in 2015). Brannavan Gnanalingham is the sole male among four finalists for the 2021 award, to be announced on May 12.

Uphill going for men

This suggests the going is harder for male novelists. Booksellers report fewer men are buying fiction. The downtown bookshops, where male city workers used to browse, have closed in favour of boutique suburban outlets aimed mainly at women with plenty of leisure time.

This background is relevant because Wilson’s novel, Taking Pagoda Mountain (By Strategy), appeals to that elusive male audience who, at the serious end of the novel spectrum, are likely to read Jonathan Franzen, Salman Rushdie, and Martin Amis.

Wilson found local publishers, while signing up four women from his class, were not inclined to invest in a picaresque adventure involving an imposter businessman-cum-artist.

The budding author was not deterred, instead opting to do it himself. He found a Wellington publisher, Your Books, and an editor, Paul Stewart, both of whom produced a trade paperback equal to the standard of Penguin or Hachette. Incidentally, Stewart’s mother is Mary McCallum, a former RNZ colleague of Wilson’s and the founder of Makaro Press, publisher of last year’s runaway hit Auē.

Pagoda is a hard novel to pin down in style, though Wilson admits to being an admirer of Ian McEwan, Vladimir Nabokov, Kurt Vonnegut, and Tom Wolfe. From his Shoeshine columns, Wilson is familiar with characters who operate in the darker corners of a business boom.

White shoe world

The story is set in the early 2000s, when property companies were a dime a dozen in the white-shoe world of Auckland, and you had to count your fingers after shaking hands on a deal. But more intriguing is the action in Shanghai, where rampant economic growth and real estate dealing make Auckland look like a backwater.

The narrator, Mark Webster, loses his wife to a successful businessman and is more interested in painting than tennis. He moves to China, where he is employed in a family business that is finding its way amid Shanghai’s opaque business scene.

He is soon enmeshed with high-living expats and well-connected locals while finding outlets for his art, based on pastiches of Mao and moko. He becomes romantically involved, too, with a woman whose intentions are harder to assess than her exterior beauty.

The couple fix their joint gaze on rescuing a pagoda near Suzhou that is in the way of a large-scale apartment and wine-growing scheme whose backers have pushed out Webster’s initial employer. The pagoda is a hideaway for their dalliance as well, it turns out, as providing an illegal vehicle for their future back in New Zealand. (Suzhou was also the location for Sir Douglas Myers’s ill-fated Lion brewery.)

None of this comes easily, with Webster attracting the attention of authorities, who hold the power of life or death. The transactional nature of relationships, both personal and business, are skilfully described, emphasising how Communist Party links and the system of favours permeate everything.

The plot races to a conclusion worthy of a Jason Bourne adventure with side helpings of Dan Brown distractions. But throughout, Wilson eschews the generic thriller style in favour of loaded Kiwiana references. Many of these have literary allusions, no doubt inspired by writing course input.

A clue to the future might be that Webster’s exploits are enough to entice his ex-wife’s husband to make a movie – perhaps in his view directed by Jane Campion under the title Owls Do Spy with a cast of characters that would make Hollywood proud.

Taking Pagoda Mountain (By Strategy), by Michael Wilson (Your Books). Available in Auckland at Unity Books, Novel Books, and Dear Reader. Or contact author at luwilson@xtra.co.nz.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.