The last word: Unreliable memory fails history

Book Review: The country’s leading man of letters has no regrets.

Book Review: The country’s leading man of letters has no regrets.

An expert on the memoir, Mary Kay, quoted St Augustine in her definitive work: “Give me chastity, Lord, but not yet.” For that reason, Kay champions confessional non-fiction over novels any day.

“In some ways, writing a memoir is like knocking yourself out with your own fist,” she writes in The Art of the Memoir (2015).

Her teaching workshops, one of which will be held at the Auckland Writers Festival, emphasise the unreliability of memory and oral recollection over the value of diaries, note taking, documents and other written material. That is why political memoirs are usually better than those of celebrities.

To be interesting, both types should contain elements of score settling, record correcting, name dropping, and revealing some dirty secrets.

The third volume of memoirs by this country’s leading man of letters, CK (Christian Karlson ‘Karl’) Stead, does not disappoint. His meticulous research is backed by impressions recorded at the time and, in many cases, checked back with those involved. It usually means getting the last word as well. This is what makes What You Made of It so valuable.

It covers the period 1987 to 2020, a time of economic and social tumult. It was also when Stead left his post as a professor of English literature at the University of Auckland to become a full-time writer.

Any serious intellectual history would include Stead’s prolific contribution to literary criticism, poetry, fiction, and public commentary. But it’s a voice that is now largely absent in academia’s embrace of critical theory of race, gender, colonialism and much else.

Settling scores

In my review of Michael (Shoeshine) Wilson’s first novel, I noted how the local literary scene had dramatically moved against the dominance of writers such as Stead and James K Baxter, along with the Maurices Gee and Shadbolt.

Stead was dismissive of professorial appointments that put race above talent – a practice now entrenched as ‘equity’ – and gained a reputation as an acerbic reactionary. In one dispute, he was accused of advocating “the ethnic cleansing of New Zealand literature” by the historian Michael King in a Metro column. After legal action, King apologised and sourced the phrase to Shadbolt’s then-forthcoming autobiography.

It was not the last skirmish resulting from Stead’s views based on the values of European culture. Several Māori and Pasifika writers withdrew permission at the last minute for their stories in a bid to sabotage the Stead-edited Faber anthology of South Pacific literature in 1994.

An earlier controversy involved some 23 writers lobbying then Internal Affairs Minister Michael Bassett over the purchase of a writers’ flat in London, similar to the Katherine Mansfield one in Menton, France.

Stead advised buying a place in Bloomsbury rather than a house on an island that was accessible only by boat and owned by a friend of the group’s two leaders. The then Labour government was embroiled in disputes of its own and the opportunity passed.

A score is also settled with Victoria University professor Roger Robinson, co-editor of the Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature (1998), who likened Stead to Tonya Harding, the American ice skater who employed someone to kneecap her rival.

In deprecatory mode, Stead recalls how RNZ’s Kim Hill managed to get him to admit Māori was stone-age culture, though he knew then (as John Banks didn’t realise more recently) that such a comment was unacceptable. Stead goes on at length to display his knowledge and admiration of the Māori world.

Correcting the record

Stead’s forensic approach to his own work, as well as that of others, takes up a large chunk of the memoir. Two episodes are worth mentioning in Stead’s use of real people and incidents in his 16 novels and collections of short stories and poetry.

One concerns Dan Davin, an official war historian and later publisher at the Oxford University Press. In Stead’s novel Talking About O’Dwyer, a group of dons reminisce after the funeral of their colleague, who in his wartime career as the pākehā commander of the New Zealand 38th (Māori) Battalion had shot an injured soldier in the head rather than let him be captured by Germans during their invasion of Crete. A curse, or mākutu, hung over the commander during his lifetime.

Davin left this episode out of his history of the Crete campaign but Stead tracked it down in the commander’s notebook.

The other incident involves Wellington writer Nigel Cox, who had disparaged Stead’s work since he left university. Cox’s early death from cancer had parallels with a story that had won Stead an international award in 2010. It was set in Croatia about a young playwright who dismissed the work of an older rival, who prayed for the former’s death. Stead notes he was aware of Cox’s article in 1994 but not of his illness and death in 1996. Instead, Stead insists he based some elements of the story on TV’s Frontline presenter Ross Stevens, who also died of cancer and had elicited the Tonya Harding comment.

Name dropping

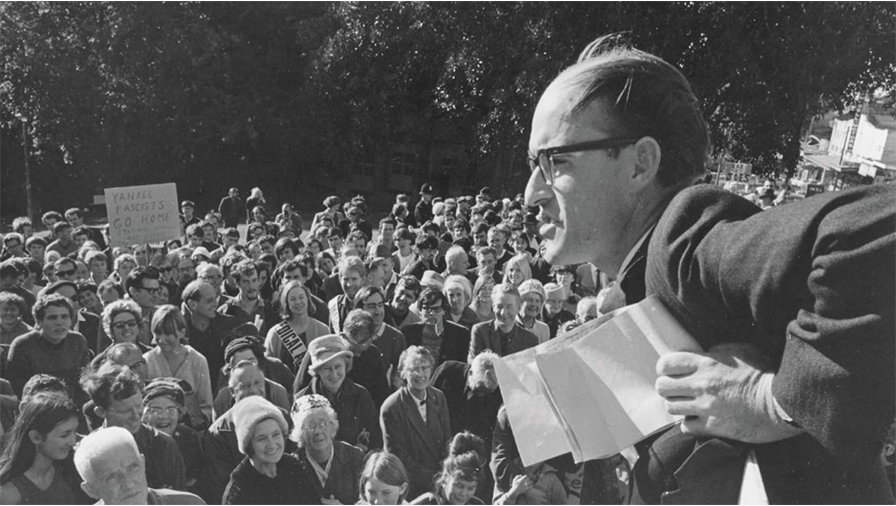

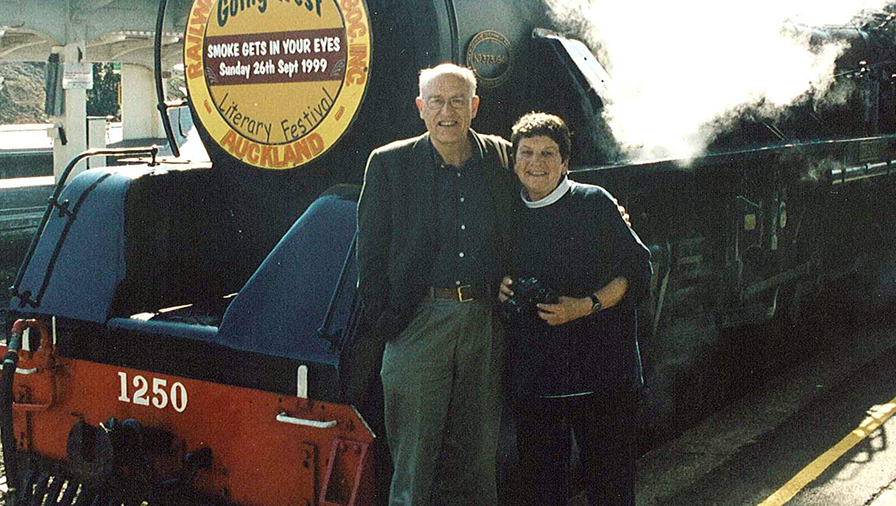

Stead, along with the late James Flynn of Dunedin, was one of the leading academics to oppose the Vietnam war in the 1960s. He also had close ties to the Labour Party; he and wife Kay were badminton partners with Helen Clark and Jim Anderton.

Stead’s credibility on the left was bolstered by his prescient first novel Smith’s Dream (1971), later filmed as Sleeping Dogs and foreshadowing the Muldoon government’s close ties with the US.

In the break-up of the fourth Labour government in the late 1980s, Stead sided with the David Lange traditionalists against the neoliberals Roger Douglas, Richard Prebble and Bassett.

Stead’s dislike of finance capitalism has never wavered, perhaps because his age (70 in 2002), international reputation, and access to world travel inured him to a fortress economy shackled by regulation.

He failed to appreciate the economic liberation that followed. Rather, his sole ‘business’ novel, Risk, was focused on political events following the 9/11 attack and the global financial crisis in 2008-09.

However, Stead does offer insights into the publishing world. New Zealand writers used to depend on a London publication to build their profile. That changed when the international companies established local operations. But publication in New Zealand meant nothing to reviewers for the London Review of Books, The Spectator and the Times Literary Supplement.

Risk (2012) fell victim to a merger of major houses Harvill and Secker & Warburg because Stead was loyal to his former publisher whose solo venture failed.

Family business

Apart from the literary scuttlebutt, What You Made of It is remarkably free of personal revelations, which is topical since the release of daughter Charlotte Grimshaw’s tell-all autobiography, The Mirror Book.

All the references to Grimshaw are positive. One anecdote is instructive. Stead devotes an entire chapter to a rebuttal of photographer Marti Friedlander’s Self-Portrait, a recorded monologue in which she relies only on memory (thus violating Carr’s rules). Friedlander recalled how Stead had soured an evening with Baron Philippe de Rothschild over Israel and Palestine.

In fact, Friedlander was not there and the evening was uneventful. Stead spells out his pro-Palestine views at length, his dislike of the anti-Semitic views of poets Ezra Pound and TS Eliot, as well as his family’s long friendship with the Friedlanders.

When Grimshaw recently reviewed a book of Friedlander’s photos, she recounts a story of how, as a five-year-old, she dropped a pétanque ball on Friedlander’s foot, partly in annoyance at the photographer’s insistent manner.

Stead describes the same event, which was passed off as accidental at the time and later used by Grimshaw herself in a piece of fiction.

Stead hasn’t commented publicly on The Mirror Book, which for some might be ‘too much information’ about the inner workings of the country’s foremost literary family. But it must surely attract heightened interest in the Auckland Writers’ Festival, at which both will appear.

Stead will participate in a closing session with six others, five of whom are referenced in less than glowing terms, with one exception.

Stead still thinks two of them, Albert Wendt and Witi Ihimaera, didn’t deserve their academic appointments. Yet Stead admires Ihimaera, once one of his students, despite flaws in The Matriarch, his major novel, and Ihimaera later having to withdraw another after admitting plagiarism.

More than any other book this year, dozens will be searching the 14-page index to see whether they pass the muster of a man once said (by Shadbolt) as a humourless, serious, boring and unreadable literary critic. Some may be pleasantly surprised.

What You Made of It: A memoir, 1987-2020, by CK Stead (Auckland University Press).

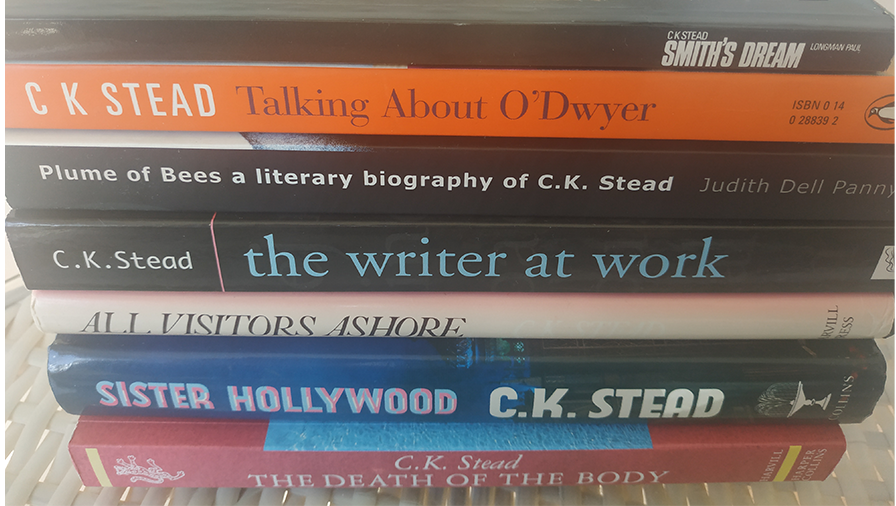

Further reading: Plume of Bees: A literary biography of CK Stead, by Judith Dell Panny (Cape Catley, 2009). The Writer at Work, essays by CK Stead (University of Otago Press, 2000).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This content is supplied free to NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.