Nelson: How a colonial riot shaped a city

Book Review: Working-class militancy disrupted the New Zealand Company’s model settlement.

Book Review: Working-class militancy disrupted the New Zealand Company’s model settlement.

A danger in the proposed new history curriculum for secondary schools is that students will learn less about their localities.

In my case, Nelson, local history was an important part of a college education. We learned of the first Polynesian arrivals on the waka Uruao in the 12th century, signs of extensive quarrying for minerals, especially argillite, up to the 16th century, and widespread cultivation of kumara and taro.

The next century saw the first encounter with Europeans. In 1642, the Dutch explorer, Abel Tasman, sailed along the turbulent west coast of the South Island into the sheltered waters of Taitapu (Golden Bay). There, over a few days, the Dutch sailors meet canoes manned by warriors of Ngati Tumatakokiri.

It did not end well, with four Dutch fatalities and at least one warrior dying. Tasman’s journal described it as Murderers’ Bay, a name later replaced by Massacre Bay.

Ngati Tumatakokiri were supplanted in the tribal wars and invasions of the 1820s. When the French navigator Dumont D’Urville arrived 1827, he mapped the area but had little contact with the unarmed locals.

It was not until 1840 that a Wellington settler, Frederick Moore, was trading coal and marble from Massacre Bay. His findings were instrumental in the London-based, Wakefield family-controlled New Zealand Company, deciding it would be an ideal place for another settlement.

Colonial origins

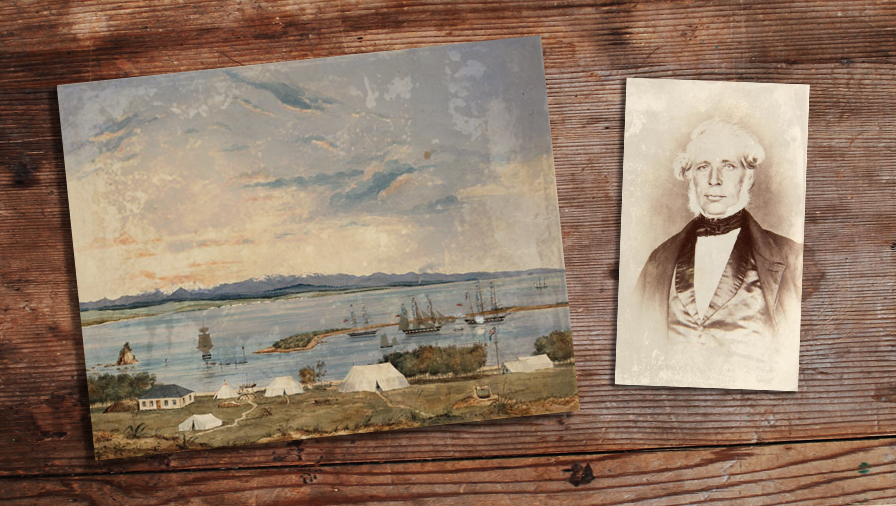

Thus began Nelson’s colonial history, with the Wakefields having sold land in Britain before the Treaty of Waitangi in 1842 cramped their style. The first ship, the Arrow, entered Nelson Haven on November 1, 1841, with two others following three days later.

The Wakefields’ planned settlement had been drawn up in London. These ships carried mainly labourers and artisans to lay out the streets that formed the town. The first immigrant ships arrived in February 1842 to find the basics of a community. These ships also brought wives and families.

By the middle of 1843, the company had sent 18 ships with a total of 1052 men, 872 women and 1384 children.

Hopes of a society that would replicate the ideal of an English town were soon dashed, as few of the immigrants owned the allotments that had been sold. The latter were the capitalists who were to provide employment. The oversupply of labour, and the lack of resident landowners to hire them, produced a classic environment for a class struggle.

It also paralleled Britain during industrialisation, as landless rural workers sought jobs in the factories, producing the Chartists, Luddites and other radical movements.

The New Zealand Company reacted by hiring gangs of labourers and effectively putting them on public relief schemes – building roads, clearing forests and draining swamps. Meanwhile, the company’s capital resources, made from selling the land back in Britain, were drained, forcing its failure in 1844.

Lively accounts

Historians have mined this period from varying points of view. Many were influenced by Karl Marx, who influenced the works of Eric Hobsbawm and Christopher Hill. Their lively accounts of workers’ movements was core reading for several generations of students. Since then, revisionist historians have put an emphasis on the role of ordinary people and, in particular, women.

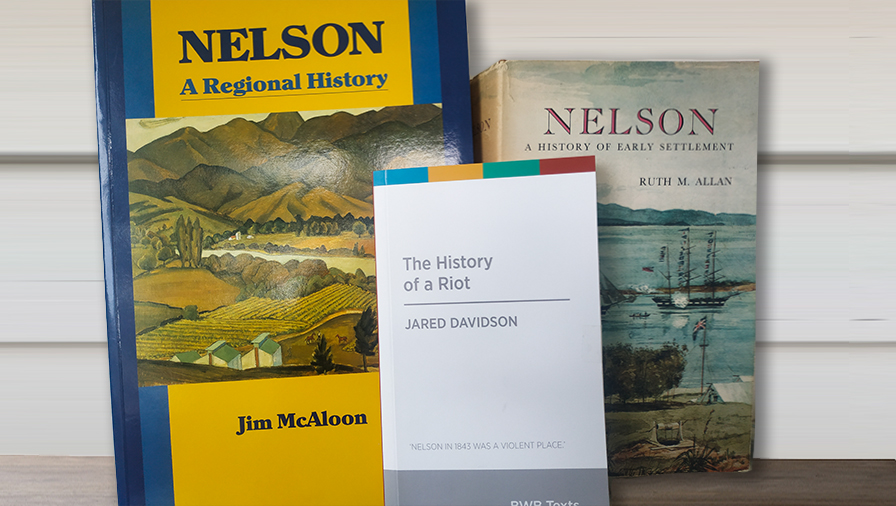

Jared Davidson's The History of a Riot is the latest addition to Nelson’s rich vein of historical writing. His account focuses on how Nelson’s gang-men (and their wives) responded to attempts to reduce their wages and rations.

During 1843, this took various forms of direct action, including strikes, go-slows and absenteeism. In January, their grievances were outlined by a lengthy petition from the “working men of Nelson” and addressed to the company boss, Captain Arthur Wakefield. The petition’s language and phrasing is worthy of being called the Magna Carta of New Zealand’s working class and is quoted in full by Ruth Allan in Nelson: A history of early settlement (1965).

The petition was followed the next day by a strike, which was quickly defused by Wakefield with some concessions. The workers’ resistance ramped up after Wakefield’s death in the Wairau Affray on June 17.

Davidson quotes the new boss, Frederick Tuckett, describing the gang-men as “indolent, insolent and contumacious”. For their part, some of the gang-men had been influenced by or involved in the Chartist movement and the Swing riots of 1830-31.

Events culminated on Saturday, August 26, pay day for the 70-80 gang-men. A physical attack on an overseer and rumours of an uprising had resulted in the police magistrate, George White, being present with Tuckett as the armed gang-men gathered outside his office.

White attempted to arrest one man, prompting the others to free him and smash up the office. The following weekend, several suspects were arrested.

White aborted their trial on September 4 because of confusion about identities, while a hostile and armed crowd besieged the court. It ended with White ordering the company to pay the lost wages.

Pleas ignored

The workers’ victory was sealed when authorities in Wellington refused White’s pleas for reinforcements to re-establish law and order. They had no intention of bailing out the company.

The “riot” – as Davidson terms it – may have faded into history’s footnotes. But it wasn’t ignored in Allan’s 450-page account of early Nelson up to 1863, or by Jim McAloon’s broad-stroked Nelson: A regional history (1997).

Davidson’s thorough research contains plenty of colourful incidents and personalities, though its appeal to the general reader is lessened by post-modernist constructs that are more suited to an academic audience.

Certainly, the events of 1843 changed Nelson’s future, if not in a way that advanced socialism. The New Zealand Co ended its supervision policies and allotted unoccupied property to many of the gang-men. These smallholdings averaged five acres (2ha) and enabled them to grow their own food. This reduced the financial burden on the company, as did the introduction of piece-work that boosted output.

By 1844, when the company went out of business, the workers’ militancy had declined and “the gang-men were not in a position to resist”. One of them, John Perry Robinson, became the district’s second superintendent from 1856-65. He succeeded Edward Stafford, who went to be the country’s effective first premier.

Small-scale farming

The Wakefields’ scheme of separating land from labour had failed, and Nelson was characterised by intensive rather than pastoral farming. McAloon says, “… the small cultivators had no intention of giving up their partial independence to a life entirely dominated by wages.”

Nelson’s remoteness reduced its economic potential well into the 20th century. Its lack of trade union militancy was reflected in 1951 when its watersiders and freezing workers were among the first to return during the government-backed lockout.

But Nelson never lost its history of protest and independence. In the 1950s, this was vented after the removal of a railway that was never connected to the main trunk line. The cancellation of a cotton mill project in 1962 sparked further protests and, for the first time, the city was represented by a Labour MP from 1957-76.

The country’s longest standing independent MP, Harry Atmore, held office from 1911-14 and 1919-46, when he was succeeded by a National MP, Gar Neale.

Nelsonians also voiced strong opposition to the Vietnam war, the Springbok tour and French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Nelson was a potent force in the Values Party of the 1970s and continues to be a stronghold for the Greens.

However, the rural electorate of Tasman, which was previously part of Buller, was held by Labour until National’s Nick Smith won in 1990. When Tasman was carved up in 1996, Smith switched to Nelson, displacing its Labour MP. Smith remained until his electorate defeat in 2020. While he returned to Parliament on the list, he retired earlier this year.

The History of a Riot, by Jared Davidson (BWB Texts).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.