My year in books – a 2023 review

A selection of good reading for the summer.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

A selection of good reading for the summer.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Compiling end-of-year lists carries risks and rewards. Many more books are published each year than anyone can ever read. The risks are that you wasted your time on the mediocre and missed out on those others admired. The rewards lie in having chosen wisely, adding to your sum of knowledge.

A good place to start for comparisons is the annual NZIER selection of summer reading for the prime minister. Last year’s selection was not a good one. It’s an open question whether that partly caused the then prime minister to resign ahead of an election year.

This year’s NZIER choices were an improvement. Three had already been recommended in this column: State of Threat, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, and The China Tightrope.

I regret not having heard of How Big Things Get Done, by Bent Flyvjerg and Dan Gardner, which was chosen for its excellent advice for handling projects by a government that aims to be the opposite of its unlamented predecessor. The book also impressed reviewers in the Economist and the Financial Times.

Steven Joyce’s On The Record.

One political memoir, Steven Joyce’s On the Record, was largely self-congratulatory but contained valuable insights on how politicians can influence bureaucratic outcomes.

The last time a Labour government excelled in rapid delivery, at least in its earliest stages, occurred back in 1972. Denis Welch’s We Need to Talk About Norman was a rose-tinted version of those times. But Norman Kirk’s tragic ignorance of his physical limitations turns the book into a hubristic warning.

This year’s change of government has not yet presented a dispassionate analysis, but publishers remained interested in the backlash from the Covid lockdowns of 2020/22.

Byron Clark’s Fear was a highly personal inquiry into alt-right extremism, pushing its boundaries out to include fringe groups in mainstream religions such as Hinduism, Catholicism, and Pentecostalism. His most interesting revelation is how the Disinformation Project, which started as an official response to anti-vaxxers, morphed into monitoring opponents of gun control; rural land rights activists; Māori sovereignty, including Three Waters; and Christian/Islamic views on abortion and gender issues.

State of Threat, a collection edited by Wil Hoverd and Deidre Ann McDonald, was a thorough and measured analysis of what dangers face New Zealand. It contains a lively debate on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which remained the front-of-mind issue for most of the year until the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel.

Veteran British diplomat Sir Roderic Braithwaite’s Russia: Myths and Realities explained the historical background, while Ukrainian-born historian Serhii Plokhy’s The Russo-Ukrainian War provided greater context as well as a blow-by-blow description of the action up to early 2023.

Another historian, Timothy Phillips, turned his knowledge of Eastern Europe into a reader’s armchair journey along the former European Cold War border in The Curtain and the Wall. A prescient chapter describes the plight of Nakhchivan, an Azeri exclave and relic of the Soviet Union. Nakhchivan lacks a link to Azerbaijan through Armenia, and this was one reason why tens of thousands of Armenians were forcibly removed from Nagorno-Karabakh in the year’s biggest forced migration.

‘The Curtain and the Wall’ by Timothy Phillips.

Life in the much-reviled former East Germany was a given a nostalgic interpretation in Beyond the Wall, by Katja Hoyer, who was born there in 1985, less than five years before the Berlin Wall fell. She found the DDR, as it was known, excelled at teaching literacy and making toys.

The citizens of North Korea were less fortunate. They live under a communist familial dynasty of which Kim Yo Jong, grand daughter of Kim Il Sung, is seen as the powerbroker most likely to take over from her brother, Kim Jong Un. Little Sister, by Korean-born academic Sung-Yoon Lee, presents her as a combination of Lady Macbeth, Madame Mao of China’s Gang of Four fame, and the Empress Dowager Cixi, who ran China in the late Qing dynasty from 1861 until her death in 1908.

The Korean civil war, in which grandfather Kim’s Soviet and Chinese-backed regime invaded the South in the 1950, features prominently in Conflict, a history of warfare since 1945 up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine by General David Petraeus and Lord Andrew Roberts, author of the seminal Napoleon the Great.

The Ukraine invasion, and the Hamas attack on Israel, took attention away from the burgeoning threat of China as the world’s second superpower. Newsroom’s Sam Sachdeva bravely ventured into this territory with The China Tightrope, which uncovered some who were prepared to criticise the greater repression under President Xi Jinping and the loss of freedoms in Hong Kong. However, others were content to keep their opinions to themselves to avoid damaging New Zealand’s economic dependence.

Conflict: The evolution of warfare from 1945 to Ukraine, by General David Petraeus and Andrew Roberts.

Seldom has an individual dominated American business in the past year as Elon Musk. He was the subject of a major biography by Walter Isaacson, whose reputation took a hammering as the largely favourable portrait appeared just before the Twitter/X meltdown. No doubt an updated version will take care of that.

Jimmy Soni’s The Founders, about the origins of PayPal, features Musk’s first successful venture before Tesla. His subsequent plunges into rockets, AI, and tunnelling made up a large chunk of Ashlee Vance’s When the Heavens Went on Sale, which also described the stratospheric success of Peter Beck’s Rocket Lab. A self-help satire, Elon Musk’s Billionaire School, by Bob Sears, took another perspective.

More straightforward accounts of doing business in the US included the unsavoury side of Amazon, Fulfillment by Alex McGillis; Unscripted, the formidable James B Stewart’s scandal-ridden tale of Sumner Redstone’s Hollywood fortune and the women who wanted their share; and Chaos Kings by Scott Patterson, about Wall Street’s contrarians who profit only when markets crash.

When the Heavens Went on Sale: The misfits and geniuses racing to put space within reach, by Ashlee Vance.

Publishers have found a new vein of gold in ‘global histories’ – mammoth works that trace the evolution of civilisations from the beginnings of time.

A leader in the field is Peter Frankopan, who previously specialised in the Silk Roads. The Earth Transformed related the environmental impact of natural disasters throughout human history up to and including the latest dystopian trend, climate change.

Martin Puchner’s Culture: A New World History emphasised the importance of archiving the past in museums, rather than allow artifacts to be left literally in the historical dust.

New Zealand’s past remained a major part of the local publishing scene. Lawyer Ned Fletcher’s aforementioned exhaustive study of the Treaty of Waitangi, reviewed last year, was a strong riposte to the latter-day revisionists.

The Taliban-style dumping of James Cook and Lord Ernest Rutherford from the country’s leading science scholarships was countered by more balanced views of New Zealand’s past achievements.

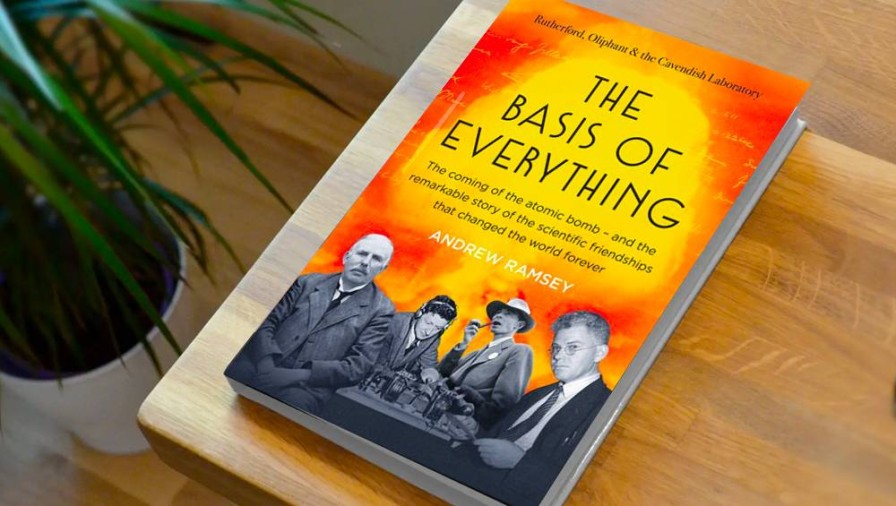

The Basis of Everything by Andrew Ramsey.

Andrew Ramsey’s joint biography of Rutherford and Australia’s Sir Mark (Marcus) Oliphant, The Basis of Everything, threw new light on background to the film Oppenheimer on another nuclear science pioneer. Ramsey attributes Rutherford's and Oliphant's scientific breakthroughs to the ‘can do’ nature of their colonial upbringing.

The impact of colonialism was also analysed in histories of penal punishment and police surveillance.

Jared Davidson’s Blood and Dirt broke new ground for its ‘bottom up’ interpretation of how convicts built much of the country’s original infrastructure, turned agriculture into a major export earner, and pioneered pine tree plantations.

Secret History, by academics Richard S Hill and Steven Loveridge, was the first of two volumes on how the police collected intelligence on the usual suspects of society’s enemies – seditionaries, subversives, and spies. The second volume, taking up the story from 1956, is due for publication next year.

Finally, in a year when intelligence gathering, whether real or artificial, has become a major area of concern, Eliot Higgins relates in We are Bellingcat how a private obsession with internet searching became a successful open-source agency that tracks the world’s evildoers.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.