Socialism in practice: Be careful what you vote for

ANALYSIS: Historian examines myths and realities of Germany’s experience.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Historian examines myths and realities of Germany’s experience.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Socialism remains the economic system of choice for people under 34 in the four main Anglophone countries, of which New Zealand is also a part.

Two free-market think tanks – Canada’s Fraser Institute and the United Kingdom-based Institute of Economic Affairs – found this unsurprising result in a 2022 survey taken in four of the Five Eyes countries: Australia, Canada, UK, and the US. New Zealand, as the missing ‘eye’, would produce similar results given the shared social, cultural, and economic model.

The poll probed attitudes toward four economic systems in five age-based cohorts. Support for socialism – defined in three forms – declined in the older (over 35) age groups. The reverse was the case for capitalism, while support for communism and fascism was marginal across the board.

In the survey’s second part, socialism was defined three ways: full state control of the economy; the government providing more services to the people; and the government providing a guaranteed income to its citizens. The latter two ways were by far the most popular.

Source: Fraser Institute

Finally, participants were asked how they preferred to pay, through a choice of new taxes. The most popular were higher rates on the top 10% of incomes and the wealthiest 1%. The answers assumed any tax increases would not affect them.

Broad-based income tax increases and higher valued-added taxes (GST) were far less popular as an alternative source for government revenue, presumably again because respondents would be affected.

New Zealand’s socialist-aligned parties, Labour, Greens, and Māori, all want higher taxes on top income earners and the wealthy as the sole sources of extra government revenue. “The clear implication is that a large proportion of supporters of socialism … want someone else to pay for the associated costs,” the Fraser-IEA survey concluded.

This paradox of socialism will not be news to anyone, even to its most fervent supporters. In a separate research exercise, the Fraser Institute tackled the perception that top income earners do not pay their share of taxes and that increasing taxes on them is an effective way to generate significant additional government revenue.

This research found high-income families already paid a disproportionately large share of all Canadian taxes. The top 20% of income-earning families paid nearly two-thirds (61.9%) of the country’s personal income taxes and more than half (53.1%) of total taxes. In contrast, the bottom 20% of income-earning families were estimated to pay only 0.7% of all federal and provincial personal income taxes and 2.0% of total taxes.

Evidence like this, which has been mirrored in some New Zealand research, is not likely to turn younger voters off socialism. Core socialist policies include subsidised rents, housing, and public transport; free childcare, education, and healthcare; equality in the workforce, paid holidays; universal benefits; and priorities on communal rather than individual interests.

All existed in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which is the subject of a refreshing assessment by a young historian who briefly lived the socialist experience. Katja Hoyer, now at King’s College London, was born in 1985 and spent her early life in Guben, a town on the border of eastern Germany and Poland.

GDR-born historian Katja Hoyer is now based in the UK.

She was only four when the GDR suddenly imploded and was absorbed by the much larger Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). Her Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990 depicts the GDR as more than just a dull, repressive rump entity occupied by the Red Army that did the Kremlin’s bidding throughout its 40-year existence.

The narrative is told in diary-like episodes, ranging from interviews with ordinary citizens to events of historical significance. Ten chapters chart the republic’s progress with headings such as ‘Risen from the ruins’, ‘Brick by brick’, and ‘Existential carefreeness’.

At its declaration in October 1949, the GDR had 18.4 million inhabitants to the FRG’s 50.4 million living in the American, British, and French occupation zones. In divided Berlin, the eastern zone had half the population of the western one.

The two Germanies were distinctly different from the one that launched the war. The FRG was split evenly between Catholics and Protestants. It had most of the industrial heartland and received generous post-war aid from the West.

By comparison, the GDR was predominantly Protestant and had an agricultural economy. It absorbed many of the Germans expelled from the loss of territory to Poland and the Soviet Union, which extracted heavy reparations in the form of factories and manpower.

In Hoyer’s account, Stalin did not envisage a separate communist German state. He made the same neutrality offer as Finland and Austria, fearing an invasion from the West against a war-weakened Soviet Union more than expanding an empire.

Politically, the GDR imitated the FRG’s MMP-based parliament, but with a set quota of seats for various political parties representing rural and other interests. All toed the line of the dominant Socialist Unity Party in a national coalition that had no opposition. Elections for the lower house merely endorsed candidates from each party’s list.

The GDR was established by communists who spent the war in Moscow, where they inherited Stalin’s paranoia and did not assert their own socialist vision until after his death in 1953. The rump state was bereft of income-producing resources and had to rebuild everything by pulling its own bootstraps. The state permanently lacked any form of capital as the private sector was expropriated.

Walter Ulbricht, the GDR’s first leader.

The pressure of the rebuild on workers was immense, sparking riots throughout the country in the 1950s. Hundreds of thousands quit the country until the borders were closed.

For all but its final few weeks, the GDR had only two leaders, Walter Ulbricht and Erich Honecker, who were both of the working class. Despite a 19-year age difference, their close friendship formed while in exile lasted until 1971 when 60-year-old Honecker forced his 78-year-old former mentor from office.

Ulbricht’s socialist aspirations were modest. He wanted a classless society, with high social mobility and the collective provision of housing, jobs, education, healthcare, and food at the cost of waiting for items such as cars and TVs.

Erich Honecker’s official portrait, 1976.

Honecker, however, identified material desires as a core element of dissent and was determined to supply consumer items that minimised odious comparisons with life in the West. As well as material wants, the GDR was generous in meeting demands for culture and entertainment. Its literacy rates were among the world’s highest; miners were encouraged to write and poets to be manual workers.

Occasionally, the cultural output was too close to Western notions for the state’s comfort. Hoyer relates the story of Dean Reed, an American sympathiser who became the GDR’s own cowboy. (Reed committed suicide in 1986 after his star had faded.)

Youth festivals and pop bands rivalling those in the West were always a feature of GDR life. New towns were created based on the same pedestrian-friendly public parks and communal facilities as the Left promotes in New Zealand. The GDR even had its own cruise ship line that plied the Baltic as well as excursions to the Mediterranean and across the Atlantic to Cuba.

In the 1960s, the experimental New Economic System encouraged long-established enterprises such as Carl Zeiss to invest in new products. Other high-tech industries were established to provide computers as well as home appliances. More households had fridges and washing machines than in the FRG.

Dolls made in the GDR were world famous.

A state-funded Department of Toys was highly successful, with bathable dolls being exported around the world. In the 1980s, 87% of all toys were exported. The Trabant car was ridiculed during its lifetime but became a cult item due to its cheap and simple mechanics.

Half of all East Germans owned a vehicle in 1988, a higher proportion than West Germans. East Germans also outdid their Western counterparts in equality of opportunity for women, tertiary education, or training skills for all who needed it. Success in international sport was partly due to systematic doping, but the GDR also had a large pool of talented athletes to draw from.

In the 1980s, as the Soviet Union staggered under economic and political stagnancy, the GDR became a beacon for socialism; its population enjoyed more leisure time than the Germans over the border. In 1988, consumption of beer and spirits was twice as high in the east than the west, in what was described as a “low-competition, collective society”.

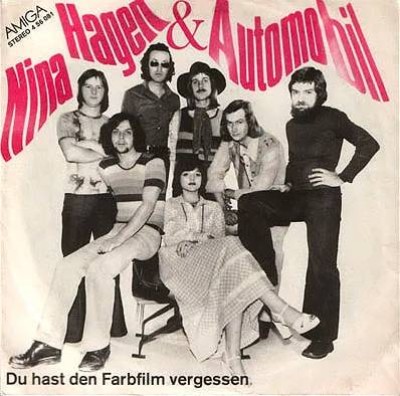

Nina Hagen’s 1976 album that Angela Merkel played at her farewell function.

Hoyer relates how Angela Merkel, who at 30 was one of the GDR’s “permanent students”, enjoyed a life of travel. She had been as far as Georgia in the Soviet Union before she went into politics after unification.

At her retirement function, Merkel chose a popular GDR song, Du hast den Farbfilm vergessen (‘You Forgot the Colour Film’), by punk star Nina Hagen, who left in the GDR 1976.

Dissenters were trafficked to the West in return for some 3.5 billion Deutschemarks, which were used for collateral in a 50-billion mark fund that imported scarce luxury goods. The GDR overcame a coffee shortage in the 1970s by investing in Vietnam, an example of foreign aid that turned a war-ravaged country into the world’s second-largest producer.

Hoyer does not ignore the many downsides of living in a country that had non-porous borders and unprecedented degrees of social control. These have been covered in previous book reviews here, here, and here. The value of her work is the light it sheds on everyday socialist life as existed, rather than the utopia reflected in the Fraser-IEA survey. Hoyer writes in English and includes detailed sources, an extensive bibliography, illustrations, and an index.

Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990, by Katja Hoyer (Allen Lane).

Disclosure: Nevil Gibson visited the GDR on several occasions and returned there just days after the fall of Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.